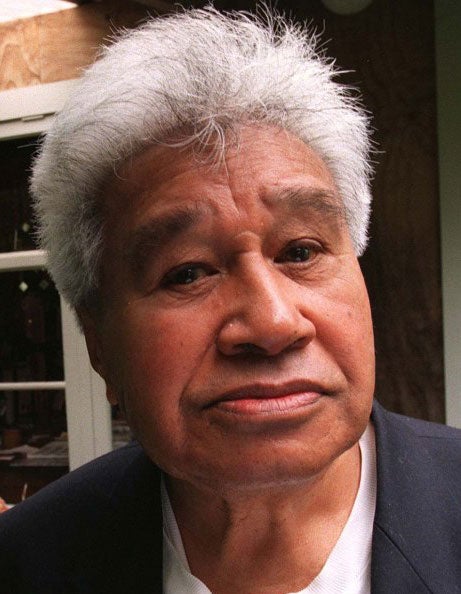

Hone Tuwhare: Maori poet whose 'No Ordinary Sun' catapulted him to celebrity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hone Tuwhare, poet: born Kaikohe, New Zealand 21 October 1922; married 1949 Jean McCormack (three sons; marriage dissolved); died Dunedin, New Zealand 16 January 2008.

When No Ordinary Sun, Hone Tuwhare's first collection of poetry, was published in 1964, New Zealand verse, through writers like R.A.K. Mason and Denis Glover, typically evoked the "Man Alone" – the post-pioneer figure. But it was a "Pakeha" (European) tradition, with a strong whiff of the university quadrangle. Tuwhare introduced a distinct Maori and working-class voice that reshaped Kiwi poetry, setting the tone for a future generation of writers.

No Ordinary Sun catapulted Tuwhare to celebrity – the first imprint sold out rapidly, and it was reprinted 10 times over three decades. The title piece, his most famous, is a microcosm of nuclear horror at weapons testing in the Pacific and drawing on his spell in post-Hiroshima Japan with the occupation forces:

Tree let your naked arms fall

nor extend vain entreaties to the radiant ball.

This is no gallant monsoon's flash,

no dashing trade wind's blast,

The fading green of your magic

emanations shall not make pure again

these polluted skies . . . for this

is no ordinary sun.

Over 40 years and 15 volumes of poetry (plus a few plays), New Zealanders took Tuwhare to their hearts. His informal, conversational style mirrored Kiwi (especially Maori) vernacular. His inspirations were vast, from simple pleasure in the landscape, or the sexiness of food (especially kaimoana, hand-gathered seafood) and the tastiness of sex, to rich combinations of Maori legend and Old Testament imagery. Political themes shot through – working man's life, Maori self-assertion and New Zealand's sporting relationship with apartheid South Africa, to name just a few.

Tuwhare's journey to celebrity was long. He was born in rural poverty in New Zealand's far north, and although the Northland landscape became a leitmotif for him, his time there was short – tuberculosis took his mother when he was seven, and the family headed for Auckland. His father, an accomplished orator, of Maori and Scottish blood, encouraged his son's literary interests, despite the family's circumstances making higher education impossible.

Aged 17, Hone Tuwhare began a boilermaker's apprenticeship with New Zealand's railways, where he read ardently in the workshop library. Joining the Communist Party (although he later left over the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956), he met R.A.K. Mason, who became his mentor. After military service, he ended up in the central North Island, where he worked on a hydro scheme and began to write seriously, with powerful evocations of working life, as here in "Monologue" (Selected Poems, 1980):

I have worked here for fifteen months.

It's too good to last.

Orders will fall off

and there will be a reduction in staff.

More people than we can cope with

will be brought in from other lands:

people who are also looking

for something more real, more lasting,

More permanent maybe, than dying. . .

Although he remained a boilermaker into the 1970s, Tuwhare's success gradually enabled him to make his living through poetry, with fellowships at Otago University in 1969 and 1974, and later spells in Germany and China. Overseas success eluded him, but he was widely honoured at home, becoming Poet Laureate in 1999 and named one of New Zealand's "10 greatest living artists" in 2003. In 2006, some of the country's leading musicians collaborated on a collection of his poems set to music.

In the 1970s Tuwhare had become active in the Maori political renaissance, organising the first convention of Maori artists and campaigning for Maori land rights. He enjoyed his fame, but was gently sceptical about the value of academic admiration, and took joy in winning over school and working-class audiences. In such a goldfish bowl as New Zealand, he carefully preserved his poetic enigma – although he was unfailingly charming to journalists who tracked him down, they would soon discover that "Hone would only talk about what Hone wanted to talk about".

His life traversed New Zealand, from the far north through Auckland and southwards, eventually to the tiny South Island village of Kaka Point, where for many years he lived simply alongside the ocean. Yet death returned him to the land of his birth, for the traditional tangi – the drawn-out funeral rite which had been a poetic inspiration ("Tangi", Selected Poems, 1980): Death was not hiding in the cold rags of a broken dirge . . . But I heard her in the wind/crooning in the hung wires . . . caught her beauty by the coffin muted to a softer pain – in the calm vigil of hands/in the green-leaved anguish of/the bowed heads of old women.

Conrad Heine

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments