Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

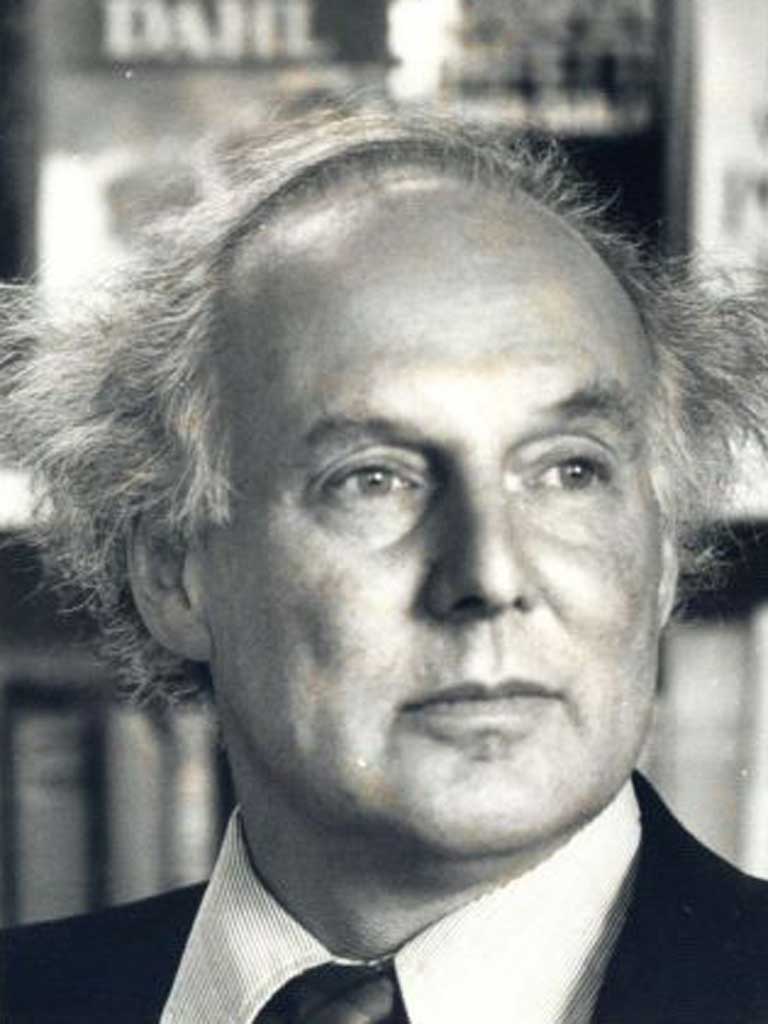

Your support makes all the difference.Hilary Rubinstein lived during a golden age of publishing, when publishers and literary agents (and he'd been both) were gentlemen, kept their words and always answered your letters. His long and mostly happy life was marked by his enthusiasms: for his family, for good books of every sort, for small, owner-run hotels and for chocolate. He was the youngest of three sons of a very old Anglo-Jewish family. One ancestor, a quill-maker, averted an attempt on the life of George III, and was rewarded with the royal warrant for quills.

Rubenstein's father, Harold, was a solicitor with a literary practice who took a scholarly interest in religion and wrote plays linking Judaism and Christianity, published by his brother-in-law Victor Gollancz. He acted for the defence in the Radclyffe Hall trial, and Hilary's older brother Michael joined the family law firm and defended in the Lady Chatterley's Lover case.

Rubenstein was educated at Cheltenham College and read PPE at Merton before spending 1944-47 in the RAF as a trainee pilot. In 1950 he was more or less apprenticed to Gollancz, his son-less but patriarchal uncle with five daughters, left-leaning, aggressive and tough-minded on every subject but religion. He exploited his underpaid nephew, whose contacts were valuable to the firm, exemplified by Hilary's discovery – while still at Oxford – of Kingsley Amis. Lucky Gollancz published Lucky Jim.

There was a diffidence about Hilary's conversational style. Immediately after speaking his first syllable, he would go quiet for a few beats, as if mentally reviewing what he had been about to say, before continuing. This was part of the attractiveness of the man, but perhaps the result of bullying by Gollancz, who never spoke to him again after he left the firm in 1963 to join the Observer Magazine, as special features editor of the new colour supplement.

He quickly moved on in 1965 to AP Watt, London's oldest literary agency, and stayed until 1992, ascending from partner to director to chairman and managing director. He was Michael Holroyd's agent (which was why he became mine more or less automatically) and made the then-record non-fiction deal for Holroyd's biography of George Bernard Shaw. Apart from this coup, AP Watt's bread and butter was the literary estates of, for example, Robert Graves, Somerset Maugham. HG Wells, Chesterton, Kipling and Yeats. Hilary's favourite living client, though, was PG Wodehouse. After retirement, he continued to represent a few friends through Hilary Rubinstein Books Literary Agency.

Sometimes his business dealings seemed a little eccentric. He agreed to represent the widow of Robert Maxwell on the grounds that she was an underdog, but let Jeffrey Archer go elsewhere. He became entangled in controversy over accepting money for Gitta Sereny's book on the Mary Bell child murder case. It was trivial, but grieved me to leave Hilary because he and a greedy publisher couldn't settle their differences about who should receive the agency commission for one of my books, leaving the author out of pocket and with no one representing his interests.

As an agent, he may have been, as one tribute says, "shrewd and adroit"; but I think much of Rubenstein's great charm was that he was not himself much interested by money, and probably couldn't see why people made such a fuss. He was a wonderful mentor for a young writer, charitable and subtle in his corrections of one's lapses of fact, tact and – worse – manners.

In 1978 he took the example of Raymond Postgate's reader-compiled Good Food Guide and published The Good Hotel Guide. Its attention to detail and keenness to discover new places put Egon Ronay's, the Michelin, and most subsequent guides to shame. His Guide has done a lot of good for the hospitality industry, which tends to focus on size and scale, distorting the consumer's appreciation of the genuine luxury that comes from having the guests' needs and wishes attended to in a personal, non-rulebook-dictated fashion. Rubenstein's own favourite was Ivan and Myrtle Allen's Ballymaloe House near Cork, where the food remains as superb as the beds are comfortable and the house and setting beautiful.

Rubenstein was (at least it appeared) a cheerful insomniac, coming to enjoy sleeplessness rather than worry about it; he even put together an anthology for reading in bed (always listed as his recreation), The Complete Insomniac (1974). He was on the Council of the ICA from 1976-92 and a trustee of the Open College of the Arts from 1987-96.

Though he worked for, and with, so many of the Great and Good (and occasionally notorious), Hilary Rubenstein was essentially a modest, lovable and good man. His greatest triumph in life was his long, happy marriage in 1955 to Helge Kitzinger. In their early days together they shared their West London house with Bernard and Shirley Williams, and later moved between it and their Oxfordshire cottage and a French farmhouse near Albi.

Appropriately, Helge Rubinstein was for many of the years of their marriage a distinguished marriage guidance counsellor. Helge's excellent 1981 book on chocolate is still a standard, and Ben's Cookies, the business she founded, is named for their youngest son. They had four children, of whom the sole daughter, Felicity, is a notable publisher and agent.

Hilary Harold Rubinstein, literary agent, publisher, editor of The Good Hotel Guide: born London 24 April 1926; Founder-editor, The Good Hotel Guide 1978-2000; Partner, Director, Chairman, Managing Director, A P Watt 1983–92; married 1955 Helge Kitzinger (one daughter, three sons); died London 22 May 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments