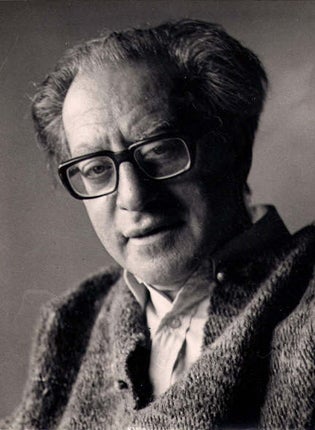

Henry Rothschild: Collector who occupied a central place in British crafts and design

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Henry Rothschild was a hugely influential figure in British crafts and design. Primavera, the shop he founded in London, showcased pottery, glass and textiles by contemporary craftspeople that might not otherwise have found an audience. He also collected ceramics, staging exhibitions and liaising with gallerists, later donating much of his collection to public institutions.

When Primavera opened in Sloane Street in 1946, at a time of great austerity, it seemed as if Rothschild had conjured attractive objects out of thin air. He sold pioneering good design, machine and hand-made, chosen with immaculate taste. In those early days Rothschild improvised – dying and selling fishermen's nets from Dorset as room dividers and offering "coupon-free furnishing fabrics" printed on parachute silk. He sold tableware from Winchcombe Pottery and from Lucie Rie's Paddington studio, textiles by the great weavers Ethel Mairet and Rita and Percy Beales, turned bowls by David Pye, baskets from the Somerset Levels, rush-seated chairs by old Edward Gardiner and specially commissioned furniture by young designers like Nigel Walters. As soon as possible he included textiles, glass and lighting by the most innovative British and Scandinavian manufacturers.

Henry Rothschild was born in Frankfurt in 1913, the fourth and youngest child of Albert and Elisabeth Rothschild, his father the director of an international family firm dealing in scrap metal, his mother from an Offenbach banking family. The typographers Rudolf Koch and Berthold Wolpe were distant relatives and Wolpe was to design the letterhead for Primavera. Even as a child Henry had a keen eye, making collections of little objects bought in Frankfurt's Trödelmarkt. His father, none the less, decided he should join the family firm and Henry embarked on a degree in chemistry and physics at the University of Frankfurt. On the advice of his tutors he left for England after Hitler came to power, going first to Chelsea Polytechnic and then to Cambridge to read natural sciences.

Serving in Italy during the Second World War (he had received his British naturalisation papers in 1938), he found himself in a pre-industrial world, watching potters near Bologna making freely decorated tin glaze and admiring traditional needlework and textiles at Assisi and Arezzo. It was a transformative experience and at Primavera Rothschild was always to include undiscovered examples of vernacular art and craft chosen for their formal beauty – Sicilian cart carvings, Marsh Arab rugs, Coptic and Nigerian textiles, Dutch pastry moulds and Polish woodcarvings, scissor cuts and tinfoil churches made as a diversion by apprentice locksmiths.

From the start Rothschild showed studio ceramics, staging one-man shows for the most adventurous sculptural potters of the post-war period including Ian Auld, Gordon Baldwin, Hans Coper, Ruth Duckworth, Gwyn and Louis Hanssen, Gillian Lowndes (an artist he deeply admired), Colin Pearson and Helen Pincombe as well as more established figures like Bernard Leach, Michael Cardew and Katherine Pleydell-Bouverie. In 1953 he organised an important British ceramics show at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and during the 1970s he curated a series of exhibitions in Germany that brought British ceramics to central Europe.

Rothschild's politics were left-liberal and he assisted in the creation of important craft and design collections formed for circulation in schools by the Greater London Council and by Bedford, Leicestershire, Bristol and the West Riding of Yorkshire education authorities. The circulation department of the Victoria and Albert Museum was another customer and he selected important pieces for the ceramics collection at Paisley Museum and Art Gallery in Scotland. This egalitarian belief in good design for all inspired him to start Primavera (Contracts) Ltd in the early 1960s.

He and a team of designers furnished university bedsitting rooms and common rooms, providing well-designed desk units and seating complemented by attractive rugs, the "university" blanket (in 10 colourways), bedspreads and curtains – "I believe good patterns and colours help the student," he said. Thus undergraduates in the Wolfson Building, St Anne's College, Oxford and at the universities of Canterbury, Exeter, Lancaster, Newcastle and York had their taste educated enjoyably and subliminally.

In 1959 Rothschild opened a branch of Primavera in Cambridge, opposite King's College, that paid special attention to artists and craftspeople locally and in East Anglia. His London Primavera (from 1967 in Walton Street) closed in 1970 but he continued to run the Cambridge branch until 1980 while curating major shows at Kettle's Yard, chiefly of British ceramics, but also staging an important survey show, "Leading German Craftsmen" (1973). His attitude towards the country of his birth was generously forgiving.

Over the years Rothschild built up a major collection of studio pottery, much of which he donated to the Shipley Art Gallery, Gateshead and to York City Art Gallery.

Rothschild could be irascible but he was also inspiring, amusing, cosmopolitan and conspiratorial. He looked and sounded like a professor, never losing his German accent. His instincts were all for the greater good and in 1990, aged 77, he founded Wintercomfort, a charity for Cambridge's rough sleepers. His passion for good art, craft and design (and for gardening and classical music) never left him – pleasures he shared with Pauline de Ste Croix, his wife of more than half a century, who predeceased him.

Tanya Harrod

Heinrich Wilhelm Jacques Rothschild, shopkeeper and collector: born Frankfurt 21 November 1913; married 1952 Pauline de Ste Croix (died 2002, one daughter); died Oxford 27 May 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments