Helen Frankenthaler: Innovative painter who took abstract art in a new direction

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1952, at the age of 23, Helen Frankenthaler painted the picture that would launch her career and free American abstraction from the heavy hand of Jackson Pollock. Pollock had already pioneered the technique known as "soak stain" painting, in which pigment is applied directly to the unprimed canvas. But where Pollock's paints were flicked on in splats or left to clot in scabby pools, the soak stains in Frankenthaler's Mountains and Sea were washed thinly over the canvas in colours and forms that seemed vaguely floral. Seen in reproduction, Mountains and Sea looks like a work on paper, probably around A4 in size and done in watercolour. Actually, it is 7ft wide by 10ft high, and the method of its making, nailed to a wall in Frankenthaler's studio, was every bit as heroic as Pollock's.

In spite of this, Frankenthaler's work was quickly pigeonholed as feminine, a mistake that plagued her to the end of her life. "For me, being a 'lady painter' was not an issue," she said, sharply. "I don't resent being a female artist, and I don't exploit it. I paint." Unable to be one of the boys, she resolutely refused to be one of the girls: in the bra-burning Sixties, her views on feminism were scathing, outspoken and unpopular. Her politics, too, were not typically those of a New York Jewish painter.

This may have had something to do with Frankenthaler's untypically patrician background as an artist. Born in the Upper East Side to Alfred Frankenthaler, a judge in the New York State Supreme Court, her upbringing was less O Henry than Henry James. The three Frankenthaler girls were educated to have careers; Helen, showing signs of a precocious talent, as an artist.

Raised on Park Avenue, schooled privately in Manhattan and finished at the progressive Bennington College in Vermont, she returned to New York in 1949 as a fully formed Cubist. These old-fashioned tastes were soon changed by the high priest of pure abstraction, Clement Greenberg. Meeting the critic, 20 years her senior, in 1950 and taking him as a lover, the elfin Frankenthaler began to make the kind of work Greenberg was known to favour. His support of her survived the end of their affair in 1955, and he included Frankenthaler in his ground-breaking 1964 show, Post-Painterly Abstraction.

By then, Mountains and Sea had changed the face of American abstract painting. Shortly after the canvas was finished, Greenberg had taken the artists Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis to Frankenthaler's studio to see it. Both men were astonished. Jackson Pollock's sculptural surfaces and muscular posturing had seemed to mark a full stop to the possibilities of abstract painting. Now, in the thin washes, wide-open spaces and luminous palette of Mountains and Sea, they saw a chance of escape from texture into colour. The three artists would become the earliest proponents of the school known (by everyone except Clement Greenberg) as Colour Field painting.

In 1958 Frankenthaler married fellow-artist Robert Motherwell. Like his new wife's, Motherwell's background was highly privileged; the Harvard-educated son of the chairman of Wells Fargo Bank, he was already on his second marriage by the time the rather younger Frankenthaler met him. Throughout the Sixties, the couple lived the life of upper-class bohemians à la Scott Fitzgerald, summering in Provincetown, spending winters in France and Spain and driving too fast in a series of ever more powerful Mercedes Benz cars. They divorced in 1971.

Marriage to Motherwell may have done Frankenthaler's career a deal of harm. An early member of the New York School – he coined the movement's name himself – Motherwell worked in a graphic, black-on-white style which seemed designed to make his wife's paintings look emotional and soft-edged. While his work was constantly on show around the world, hers did less well: her first one-woman exhibition was in 1960, and then at the Jewish Museum of New York rather than, say, the Museum of Modern Art. Frankenthaler would be in her sixties by the time she was finally given a MoMA retrospective, in 1989. By that time, she was sitting as a presidential appointee to the National Endowment for the Arts, the American equivalent of the Arts Council; a post that seemed entirely in keeping with her patrician background and intuitively grand manner.

This appointment also highlighted Frankenthaler's distinctly un-bohemian politics. Writing in the New York Times in 1989, she criticised government subsidies of the arts as "not part of the democratic process", adding that state funding was "beginning to spawn an art monster". As a direct result of her views, the NEA, under the administration of George Bush Senior, cut grants to artists whose work Frankenthaler disliked – Andres Serrano, creator of Piss Christ, was perhaps the best-known victim – and slashed the Endowment's budget as a whole. All this made Frankenthaler unpopular in younger and more avant garde art circles, although – by now married to a Republican banker and living in the upper-class enclave of Darien, Connecticut – this seems not to have bothered her unduly.

Like all painters, Frankenthaler's reputation suffers from the confusion between life and art. As with many others, her later career seems less distinguished than her earlier: although she moved from oils into acrylic from the 1970s on and began to use Japanese woodblock images in her paintings, she never replicated the excitement of Mountains and Sea. None of this explains the sharp division of critical opinion on her work, which has tended to be either fawningly laudatory or vicious. In the latter camp is the critic of the Los Angeles Times, who has dismissed Frankenthaler as "a minor formalist artist" and Mountains and Sea as a work of "slight innovation". It is impossible to know whether he would have written these words had Frankenthaler been less privileged or politically conservative, or if she had been a man.

Charles Darwent

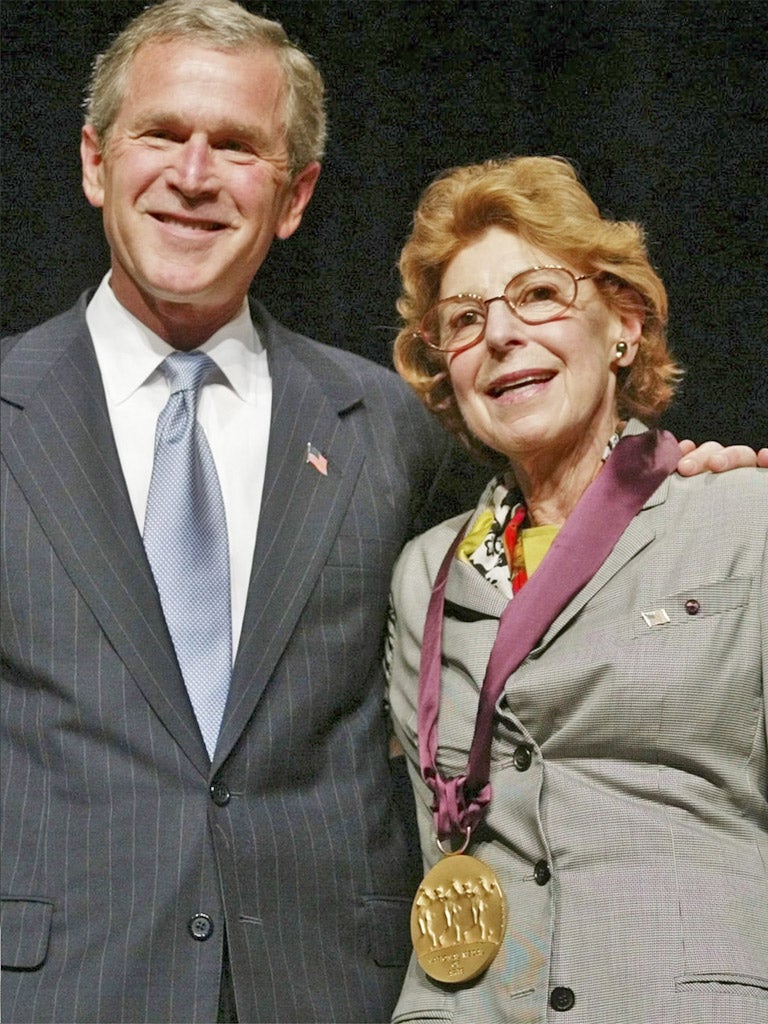

Helen Frankenthaler, artist: born New York City 12 December 1928; married 1958 Robert Motherwell (divorced 1971), 1994 Stephen DuBrul (died 4 January 2012); National Medal of Arts, 2001; died Darien, Connecticut, 27 December 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments