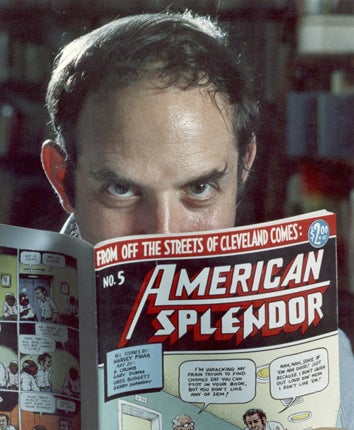

Harvey Pekar: Writer who celebrated the minutiae of everyday life in his 'American Splendor' series

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The "underground commix" of the Sixties took comic books, once the domain of superheroes and funny animals, into more adult territory. Harvey Pekar moved those adult concerns to a different level.

As the writer of the series American Splendor, Pekar dealt with the most boring miniutiae of everyday life in the decaying city of Cleveland, Ohio. While similar in some ways to the work of his friend Robert Crumb, who illustrated his first strips and described Pekar's work as "so staggeringly mundane it verges on the exotic", Pekar's characters were less comically exaggerated than Crumb's, and less likeable.

He never spared himself, and one of the glories of the 2003 film American Splendor, which cleverly mixes his life and work just as he did himself within the graphic medium, is the way Paul Giamatti, playing Pekar, avoids playing him like a Woody Allen character, searching for sympathy for his neurotic humour. Pekar is sometimes compared to Russian realists like Dostoyevsky or Gogol, but a closer match might be Henry Miller, the novelist who insisted that the stuff of his everyday life was just as important, just as suitable a subject for fiction, as anyone else's.

Pekar produced his comix while working for 36 years as a file clerk in a Veteran's Administration hospital. It was boring, repetitive work but he consistently refused promotion, fearing extra responsibility, leaving himself time, originally to work as a jazz critic. It was through their mutual mania for record-collecting that he first met and bonded with Crumb.

Pekar was born in 1939 in Cleveland to immigrant Polish Jews. Although his father was a Talmudic scholar they ran a grocery above which the family lived. After the war, the neighbourhood changed into one that was largely black, and Pekar was often bullied. The family moved to the largely Jewish suburb of Shaker Heights, and Pekar, having been bullied for his perceived privilege, now found himself looked down on by the more affluent, and was seen as something of a tough guy in his new neighbourhood. He began exhibiting a chronic fear of success, as detailed in his 2005 book The Quitter (illustrated by Dean Haspiel).

After high school he enrolled at nearby Case Western Reserve, but soon dropped out. Before being hired by the VA in 1965 he worked a series of menial, dead-end jobs, which left him time to write for the magazine Jazz Review. At one point he joined the Navy but was discharged because, as he explained, his anxieties caused to him to fail every inspection.

He met Crumb, a teenager drawing for Cleveland's American Greeting Cards, in 1962. As Crumb's underground work became more and more successful, Pekar said he spent a decade contemplating the idea of using the form to tell his own stories. He produced scripts illustrated with stick figures which so impressed Crumb that he illustrated them for his own People's Comix in 1972. Artists as varied as Spain Rodriquez or Richard Corben flocked to draw his stories for various underground commix, but Pekar wanted to do longer pieces and began self-publishing the American Splendor series in 1976.

Eventually, they would be selling some 10,000 copies an issue, helped by his winning an American Book Award for a 1987 collection, and by his appearances on David Letterman's late-night TV chat show. Inevitably Pekar bristled at Letterman's using him as a comic resource, and in 1988 on one programme launched into a tirade, branding Letterman a "shill" for NBC's corporate owners, General Electric, who were also one of America's biggest military contractors. He would not return until 1993.

By then he had survived a diagnosis of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; the medical benefits provided by his menial job proved essential. He and his third wife Joyce Brabent collaborated on Our Cancer Year (1994), illustrated by Frank Stack, which detailed his struggles and the strains on their relationship. Their 1983 marriage was announced in an American Splendor issue titled "Harvey's Latest Crapshoot", which detailed their first date, on which his home-cooked meal gave her food poisoning.

After beating cancer, Pekar's attitude towards marketing his work changed. In 1992 he began a four-year run writing a jazz strip, illustrated by Joe Sacco, for Village Voice. He went with mainstream publishers for American Splendor, Dark Horse from 1994-2002 and then, after the success of the film and an American Splendor collection (Doubleday, 2006), DC Vertigo. His subjects also widened. He wrote American Splendor: Unsung Hero, about his fellow VA worker and Vietnam veteran Robert McNeill, and a series of non-fiction works, including studies of the Sixties radical group Students for a Democratic Society (2008), the Beat poets (2009) and a graphic adaptation of Studs Terkel's Working (2009). But even then he said he considered himself "too insecure, obsessive and paranoid" to think of himself as a success.

He was found dead at home by his wife. Although no cause of death was announced, the police told the press that Pekar suffered from "prostate cancer, asthma, high blood pressure and depression". It might have been a panel from one of Pekar's comics.

Harvey Pekar, writer: born Cleveland, Ohio 8 October 1939; married firstly, secondly, 1983 Joyce Brabent (one adopted daughter); died Cleveland Heights 12 July 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments