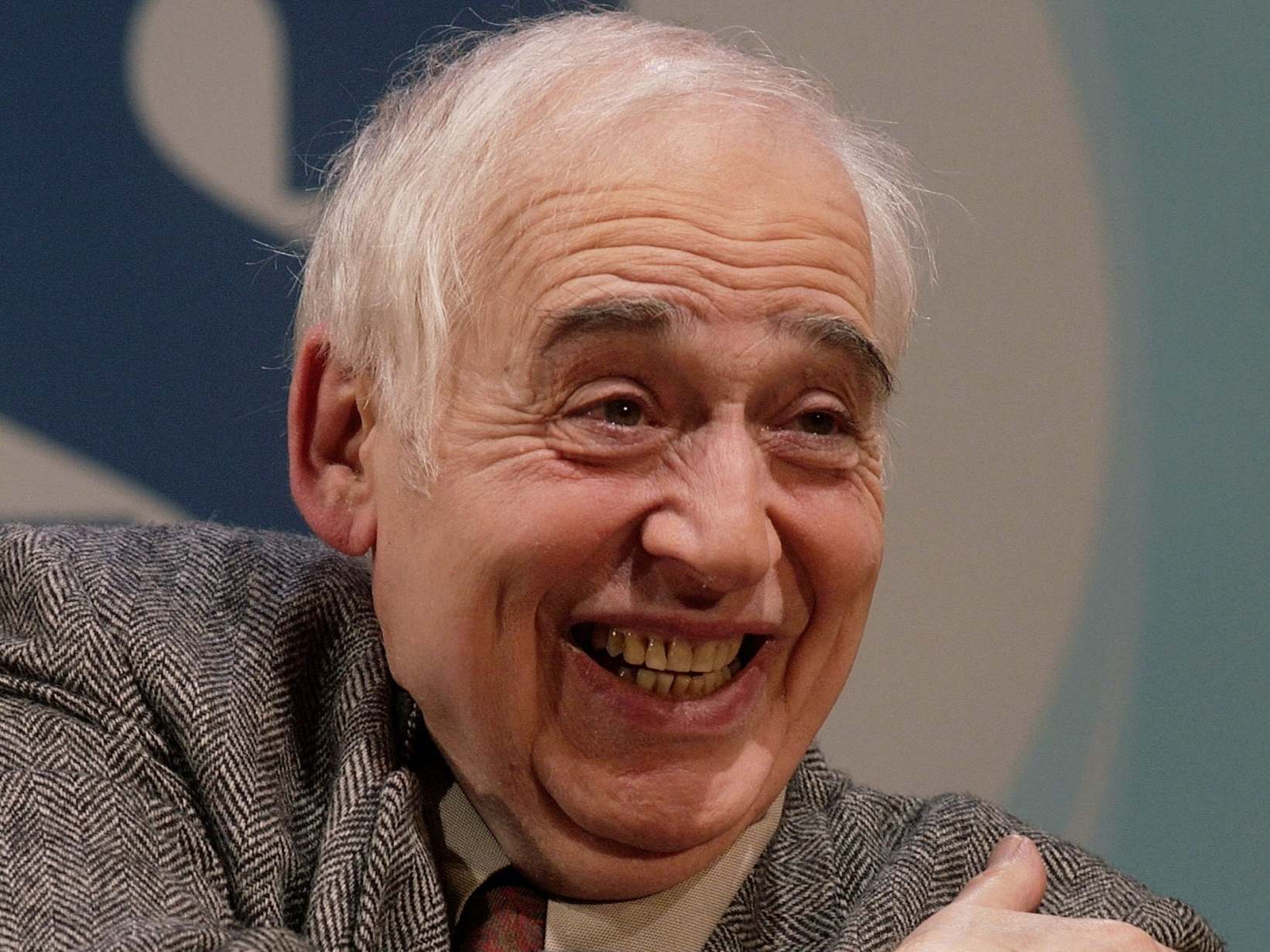

Harold Bloom: Literary critic and bestselling author who challenged the orthodox

He made the scholarly accessible to a larger audience, though to many he was elitist and out of touch

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Harold Bloom was an eminent critic and Yale University professor whose seminal The Anxiety of Influence and melancholy regard for literature’s old masters made him a popular author and standard-bearer of western civilisation amid modern trends.

Bloom, who has died aged 89, wrote more than 20 books and prided himself on making scholarly topics accessible to the general reader. Although he frequently bemoaned the decline of literary standards, he was as well-placed as a contemporary critic could hope to be.

He appeared on bestseller lists with such works as The Western Canon and The Book of J, was a guest on Good Morning America and other programmes and was a National Book Award finalist and member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. A readers’ poll commissioned by publisher the Modern Library ranked The Western Canon at No 58 on a list of the 20th century’s best nonfiction English-language books. But he was not a stranger to controversy. In 2004 the author Naomi Wolf wrote that Bloom had made unwanted advances while she was attending Yale. He denied the allegation.

His greatest legacy could well outlive his own name: the title of his breakthrough book, The Anxiety of Influence. Bloom argued that creativity was not a grateful bow to the past, but a Freudian wrestle in which artists denied and distorted their literary ancestors while producing work that revealed an unmistakable debt. He was referring to poetry in his 1973 book, but “anxiety of influence” has come to mean how artists of any kind respond to their inspirations. His theory has been endlessly debated, parodied and challenged – including by Bloom himself.

Bloom openly acknowledged his own heroes, among them Shakespeare, Samuel Johnson and the 19th-century critic Walter Pater. He honoured no boundaries between the life of the mind and life itself and absorbed the printed word to the point of fashioning himself after a favourite literary character, Shakespeare’s betrayed but life-affirming Falstaff.

Bloom’s affinity began at age 12, when Falstaff rescued him from “debilitating self-consciousness”, and he more than lived up to his hero’s oversize aura in person. For decades he ranged about the Yale campus, with untamed hair and an anguished, theatrical voice, given to soliloquies over the plight of modern times.

He was born in 1930 in New York’s East Bronx, the youngest of five children. His parents were Orthodox Jewish immigrants from Russia, neither of whom ever learned to read English.

Bloom’s literary journey began with Yiddish poetry, but he soon discovered the works of Hart Crane, TS Eliot, William Blake and other poets. He would allege that as a young man he could absorb 1,000 pages at a time. “The sense of freedom they conferred”, he wrote of his favourite books, “liberated me into a primal exuberance”.

He graduated in 1951 from Cornell University, then was a Fulbright Scholar at Pembroke College at the University of Cambridge. After earning his doctorate from Yale in 1955, he joined the university’s English faculty.

In the 1950s Bloom opposed the rigid classicism of Eliot, but in the following decades he condemned Afrocentrism, feminism, Marxism and other movements he placed in the “school of resentment”. A proud elitist, he disliked the Harry Potter books and slam poetry, and was angered when Stephen King received an honorary National Book Award. He dismissed as “pure political correctness” the awarding of the Nobel Prize in Literature to Doris Lessing, author of the feminist classic The Golden Notebook.

“I am your true Marxist critic”, he once wrote, “following Groucho rather than Karl, and take as my motto Groucho’s grand admonition, ‘Whatever it is, I’m against it.’”

In The Western Canon, published in 1994, Bloom named the 26 crucial writers in western literature, from Dante to Samuel Beckett, and declared Philip Roth, Thomas Pynchon and Don DeLillo among the contemporary greats. Shakespeare reigned at the canon’s centre, the inventor of our modern, self-conscious selves, a patriarch so mighty that Freud, Tolstoy and other latter-day masters nearly drove themselves mad rejecting him. “Freud is essentially prosified Shakespeare,” Bloom wrote.

He faced harsh criticism from detractors he called “lemmings”. Observers noted that The Western Canon featured a good number of Yale-affiliated poets on its list of important living American authors. Bloom was mocked as out of touch and accused of recycling a small number of themes. “Bloom had an idea; now the idea has him,” British critic Christopher Ricks said.

Bloom did not restrict his praise to white men. In The Book of J (1990), he stated that some parts of the Bible were written by a woman. (He often praised the God of the Old Testament as one of the greatest fictional characters.) He also admired Virginia Woolf, Jane Austen, George Eliot and Emily Dickinson; among the hundreds of critical editions of books he edited were works on Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou and Amy Tan.

Bloom wrote one novel, The Flight to Lucifer, but was no more effective than most critics attempting fiction, and he later disowned the book. In The Anatomy of Influence, released in 2011, Bloom called himself an Epicurean who acknowledged no higher power other than art and who lived for “moments raised in quality by aesthetic appreciation”.

He is survived by his wife, Jeanne Gould, and two sons.

Harold Bloom, literary critic and author, born 11 July 1930, died 14 October 2019

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments