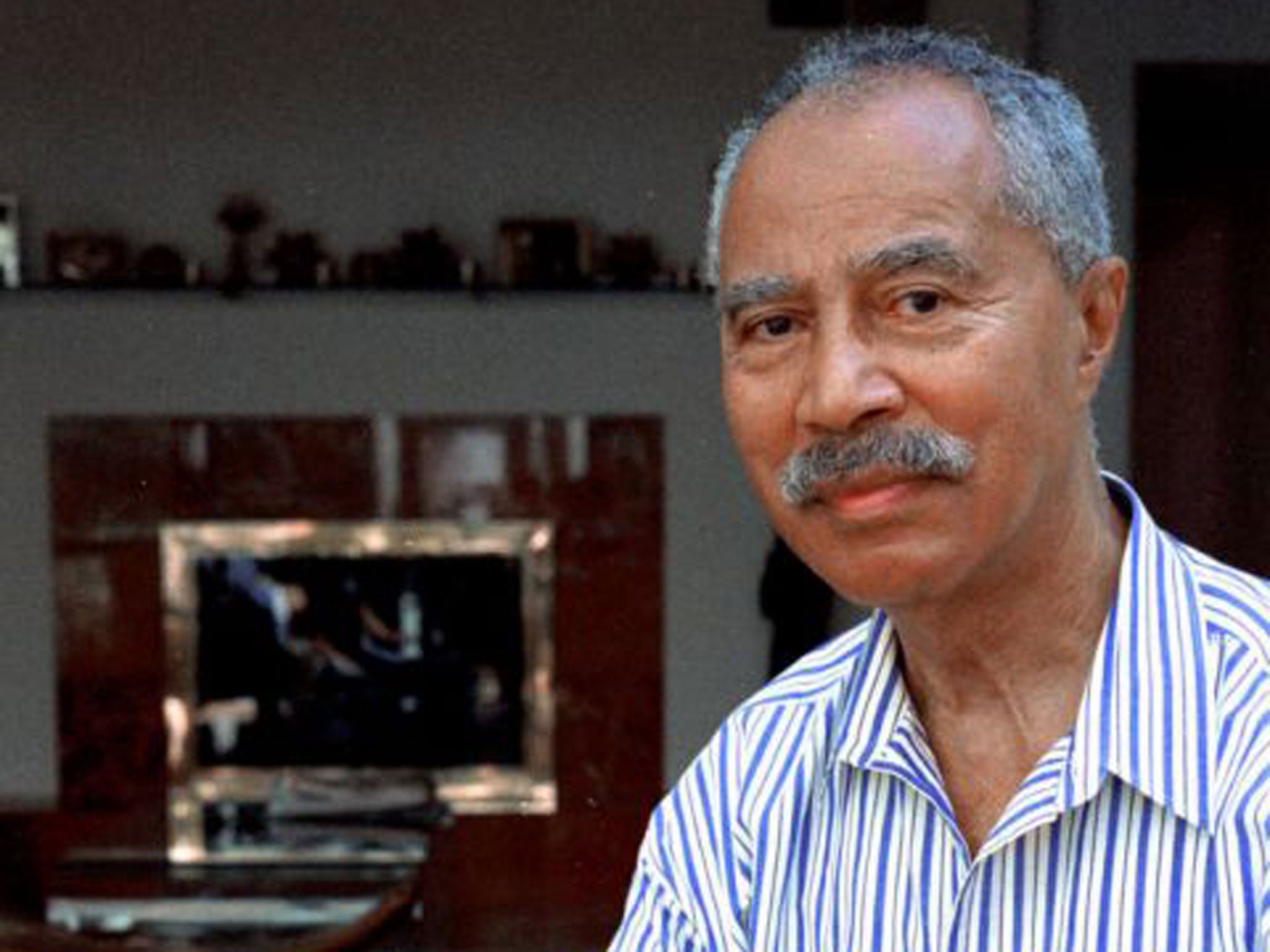

Hans Massaquoi: Journalist who grew up black in Nazi Germany

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hans Massaquoi, who died on 19 January at the age of 87, was a former managing editor of Ebony magazine who wrote a memoir about his childhood growing up black in Nazi Germany. "He had quite a journey in life," said his son, Hans Jr.

Massaquoi said he credited Alex Haley, author of Roots, for convincing him to share his experience of being "both an insider in Nazi Germany and, paradoxically, an endangered outsider". Destined To Witness: Growing Up Black In Nazi Germany was published in the US in 1999, and a German translation was published.

Massaquoi's mother was a German nurse and his father was the son of a Liberian diplomat. He grew up in working-class neighbourhoods of Hamburg. He recounted the story of a school photograph from 1933. Wanting to show what a good German he was, Massaquoi said he cajoled his babysitter into sewing a swastika on to his sweater. When his mother spotted it that evening, she cut it off, but a teacher had already taken a snapshot. Massaquoi, the only dark-skinned child in the photograph, is also the only one wearing a swastika.

He writes that one of his saddest moments as a child was when a teacher told him he could not join the Hitler Youth. "Of course I wanted to join," he said. "I was a kid and most of my friends were joining. They had cool uniforms and they did exciting things – camping, parades, playing drums."

Germany was at war by the time he was a teenager, and he describes in the book the near-destruction of Hamburg during the Allies' Operation Gomorrah bombing attack in the summer of 1943. He wrote about becoming a "swingboy" who took great risks by playing and dancing to versions of American swing music, which was condemned by the Nazi regime.

After the collapse of Germany at the end of the war, he said he saved his mother and himself from starvation by playing saxophone in clubs that catered to the American Merchant Marine. Eventually he left Germany, first joining his father's family in Liberia before going to Chicago to study aviation mechanics.

He was drafted into the US Army while on a student visa in 1951. Afterward, he became a US citizen and eventually became a journalist. He worked first for Jet Magazine before moving to Chicago-based African-American publication Ebony, where he rose to managing editor before retiring in the late 1990s.

"Many have read his books and know what he endured," his son said. "But most don't know that he was a good, kind, loving, fun-loving, fair, honest, generous, hard-working and open-minded man. He respected others and commanded respect himself. He was dignified and trustworthy. We will miss him forever and try to live by his example."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments