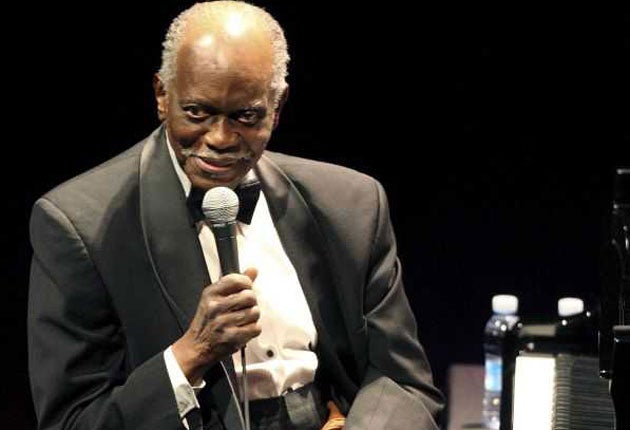

Hank Jones: Pianist whose collaborators included Miles Davis, Ella Fitzgerald – and Marilyn Monroe when she sang to JFK

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The cavernous echoing and banging of folding seats at the almost empty ground of Middlesborough Football Club is hardly a good setting for recitals by two of the most gentle and cerebral of all jazz pianists. Yet it was at a jazz festival held at the ground that both Hank Jones and Bill Evans made their British debuts in 1976.

Like Evans, Hank Jones was a delicate and thoughtful improviser, more at home in the concert hall or recording studio. So much in demand was he throughout his career that it's estimated that he appeared on over a thousand recordings. His keyboard technique was colossal – the result of powerful concentration whenever he played – and he was regarded as the accompanist par excellence, working for Ella Fitzgerald for almost five years and for Marilyn Monroe for one night.

He accompanied Miss Monroe in 1962 at Madison Square Garden on that famous night exactly 48 years ago today when she sang "Happy Birthday" to President Kennedy.

"She did 16 bars," he said. "Eight bars of 'Happy Birthday' and eight bars of 'Thanks for the Memory'. We rehearsed those 16 bars for eight hours. So I think that's something like a half-hour for a bar of music. She was very nervous and upset. She wasn't used to that kind of thing. And I guess who wouldn't be nervous singing 'Happy Birthday' to the president? She actually was a very good singer; however, on this particular occasion I think she was somewhat hampered by having imbibed rather freely. And it was very interesting. I didn't know that Kennedy was in the audience until she sang this song, 'Happy Birthday to You, Mr. President'."

But that was trivia to the stoical pianist, who in his time had played for every jazz musician of note, from Louis Armstrong to Charlie Parker to Frank Sinatra. His playing was like silk, delicate and flawless, but with a tough spine. He knew his own worth, but was modest and dignified, never once showing off or indulging in piano pyrotechnics. His improvisations were ever a model of clarity.

"When you listen to a pianist," he said, "each note should have an identity; each note should have a soul of its own. I try to play evenly. I don't take too many excursions. I don't go too far away from the melody, I don't go out into the deep water. I want the listener to understand what I'm doing. I try to stay pretty much right down the middle and yet keep it interesting."

Jones was the third of 10 children in a family that was both musical and deeply religious.

"My father thought all my energies should be directed towards playing in the church," he said. "He thought playing jazz was the work for the devil." Jones inherited his father's fastidiousness, always saying grace before a meal and never drinking, swearing or smoking. His two younger brothers matched his talents in jazz, Thad Jones being a gifted trumpeter and arranger and Elvin one of the best of the post-Buddy Rich drummers.

He was born in Mississippi but the family moved to Pontiac in Michigan where he grew up. He took sporadic piano lessons from the age of 12 and began playing professionally across Michigan and Ohio when he was 13. He stayed in the area until his mid-20s. In 1944 he was working with a territory band that had Lucky Thompson on tenor sax. Impressed, Thompson invited Jones to New York, where he arranged a job for him playing with the trumpeter Hot Lips Page at the Onyx Club.

Jones found plenty of work around 52nd Street, the jazz centre that had become the crucible of bebop. His playing style had emerged from his listening to Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, Earl Hines and Art Tatum, and although deeply rooted in swing he was already filtering in ideas from the new music. He joined groups led by Andy Kirk, John Kirby, Billy Eckstine and, at the Spotlite Club in 1946, by Coleman Hawkins, who also had in his band the young Miles Davis and Max Roach.

In 1947 Norman Granz enrolled Jones in his "Jazz at the Philharmonic" (JATP) road show, where he worked with Buddy Rich and Ray Brown backing Charlie Parker, Lester Young, Coleman Hawkins, Buck Clayton and a host of giants including Ella Fitzgerald. Granz moved Jones gradually to play solely as the singer's accompanist.

One of Jones' ambitions was to make a two-piano album with Oscar Peterson, the man who succeeded him in JATP. But Jones always drove a hard bargain, and although he regarded Peterson as the finest of all living jazz pianists, over years of trying Granz was unable to come up with a contract for the partnership that would satisfy him.

Jones joined trombonist Tyree Glenn's band in 1953 and that year was pianist in the Gramercy Five, Artie Shaw's last small group before he walked away from jazz. Jones stayed with Shaw until June 1954. From March 1955 to January 1956 his trio with bassist Wendell Marshall and drummer Kenny Clarke became the house band at Savoy Records, recording many albums backing the label's stars, but also producing a multitude of trio recordings including the masterful Have You Met Hank Jones? solo piano album (1956). In 1956 he also joined Benny Goodman's band, beginning an off-and-on working relationship that lasted for 20 years. In 1959 he became a staff pianist at the CBS studios, holding the job for 14 years.

"It was very confining," he said. "There was no time for any other playing because you were on 24-hour call." He worked for long spells on the shows of Ed Sullivan and Jackie Gleason before CBS closed their music department in 1974. Now free to tour, he appeared annually at the Nice Jazz festival until the end of the decade. "I did freelancing too, but very few nightclubs."

It was appropriate that in 1979 he became musical director of the Broadway musical Ain't Misbehavin', a show built on the music of his first love, the pianist Fats Waller. He stayed with the show for five years – leaving, typically, over a dispute about his contract.

By now his stature was recognised and he played concerts as a soloist and in duets with many other pianists, including John Lewis, Marian McPartland, Tommy Flanagan and George Shearing. Jones continued to record and appear in concerts until fairly recently, forming a particularly potent partnership with Joe Lovano, a saxophonist more than 30 years his junior.

He continued to play at festivals and last year performed in the Newport Festival in New York and toured Europe, appearing in Vienna, Paris, Geneva, Prague and Istanbul. Among his many awards he was nominated for five Grammys and last year received a Grammy for lifetime achievement. He was given the National Medal of Arts and the National Endowment of the Arts' Jazz Masters Award.

"Hank was the perfect pianist," said Bill Charlap, one of Jones' younger successors. "He was a consummate artist and a consummate professional. He had it all – he played the past, the present and the future all at the same time."

Henry "Hank" Jones, pianist: born Vicksburg, Mississippi 31 August 1918; married Theodosia (one daughter); died New York 16 May 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments