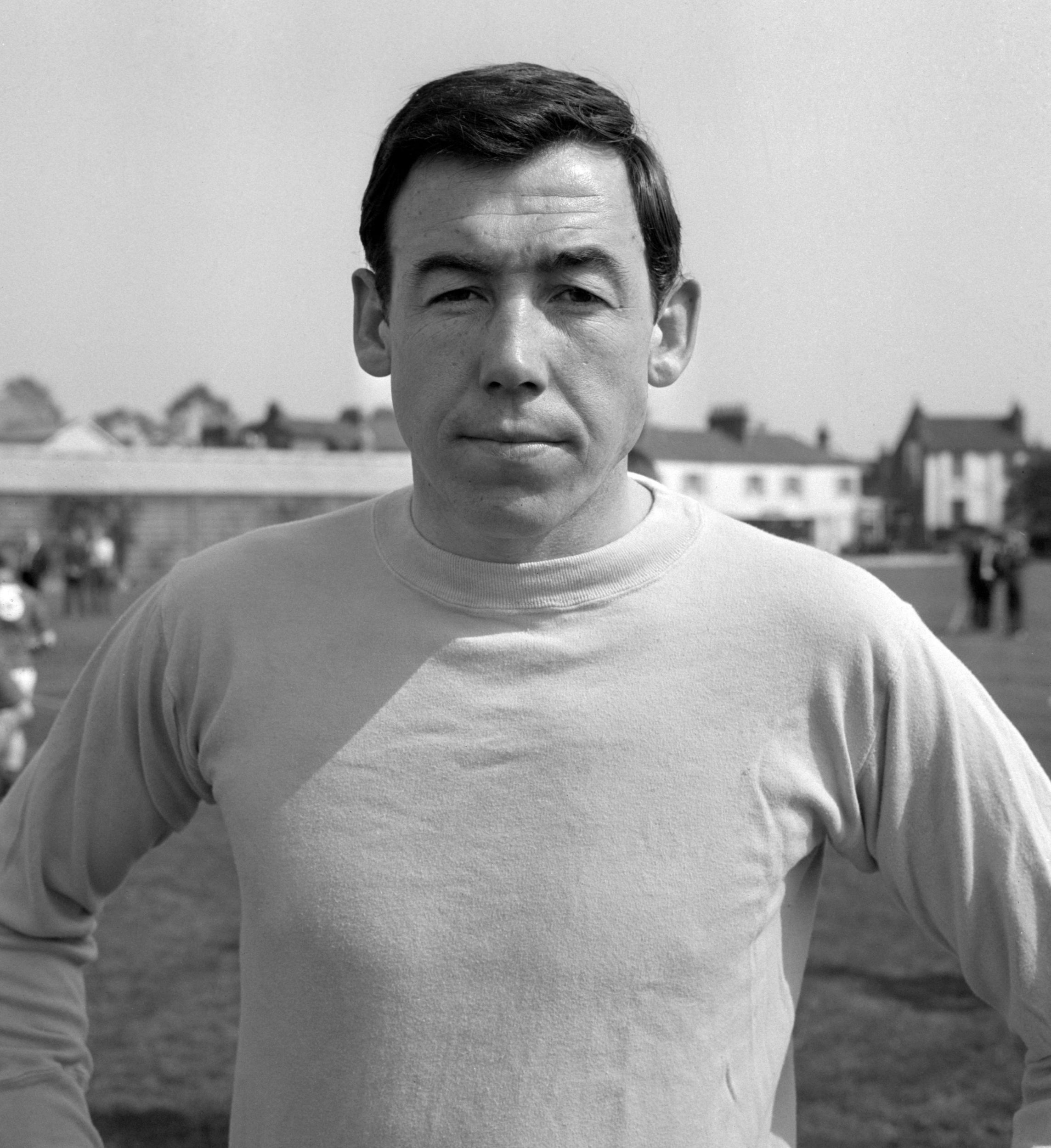

Gordon Banks: England goalkeeper who helped team to World Cup glory in 1966

Three Lions’ shot-stopper who went on to become the best in the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There were no ifs or buts or maybes; Gordon Banks was the best goalkeeper in the world, setting fresh standards of excellence, inspiring a generation of imitators and remaining at the pinnacle of his profession even in a league blessed with a plethora of brilliant custodians.

Already exceptionally accomplished when he helped England to win the World Cup at Wembley in 1966, he touched rarefied new heights when Sir Alf Ramsey’s team attempted to defend their crown in Mexico four years later.

One save in particular, a breathtakingly acrobatic flip to deny Pele when a goal seemed inevitable, earned Banks global lionisation, which was ironic as his footballing credo expressly eschewed the unnecessarily flamboyant.

He wrote in his 2002 book Banksy: My Autobiography: “The mark of a good goalkeeper is how few saves he has to make during a game. A spectacular save is the last resort when all else – positioning, anticipation, defence – have failed.

Banks, who has died aged 81, played 73 times for his country, a record which might have been extended but for a car accident in which cost him the sight in his right eye.

Yet, remarkably for such a universally admired performer, he never represented a fashionable club. Although he was hugely influential as both Leicester City and Stoke City won the first major trophies in their respective histories, the question will always be asked: what might he have achieved with Liverpool, Manchester United or Arsenal, all of whom spurned the opportunity to sign him when he was in his pomp?

It was an era when strikers changed hands for £200,000 yet somehow – despite the obvious fact that then as now, a goal saved was as important as a goal scored – the top custodians remained chronically undervalued. The equable Yorkshireman was allowed to change employers for a mere £52,000 in 1967.

The youngest of a steelworker’s four sons, Banks grew up in a grimy Sheffield suburb before leaving school to work as a coalman’s mate, then as an apprentice bricklayer. Humping sacks and lugging hods represented unglamorous graft but they helped to build up a muscular physique which served him admirably as he made his way as a goalkeeper in local amateur football.

Not that Banks’ early progress was especially meteoric, he was released by one club, Rawmarsh, after conceding 15 goals in two games. However, his clear potential earned him selection for Sheffield Boys and, despite being overlooked by hometown clubs Wednesday and United, he was spotted by Chesterfield of the Third Division North, for whom he signed as a part-timer in 1953.

During this period he set about learning his trade and honing his natural talent, which became increasingly evident during a 1954-55 season spent minding the net for the Spireites reserves. It was a poor team, which let in 122 goals as it finished bottom of the Central League, but Banks shone and the following season his ability was revealed to a wider audience as Chesterfield progressed unexpectedly to the final of the FA Youth Cup.

Facing some of the brightest young talent in the English game, the likes of Bobby Charlton and Wilf McGuinness, the underdogs excelled themselves against Manchester United, narrowly losing out 4-3 courtesy of a disputed late winner.

In November 1958, the 18-year-old made his senior debut and acquitted himself so capably that he retained his place for the remainder of the campaign, which was to be his last at Saltergate.

Chesterfield were desperately short of cash and when Leicester City of the old First Division offered £7,000 for his services in the summer of 1959, a deal was swiftly completed.

At Filbert Street, Banks found himself competing with five other senior keepers, but soon he emerged as the pick of the bunch, and that autumn he unseated Dave MacLaren to win a regular place in manager Matt Gillies’ combative side.

With Banks increasingly reliable behind an organised rearguard, and with the spirited Frank McLintock in midfield, Leicester enjoyed their finest season to date in 1960-61, finishing sixth in the League and reaching the FA Cup Final, where they lost 2-0 to the champions, Tottenham Hotspur.

Sadly, little went right for City at Wembley, having already lost centre-forward Ken Leek for disciplinary reasons, then being reduced to 10 men early in the game through injury to Len Chalmers (before substitutes were allowed), but Banks underlined the qualities that had recently earned him an England under-23 call-up.

Both brave and strong, with an ability to catch practically every ball within reach of his big hands, he was also blessed with a natural elasticity accentuated by a single-minded devotion to training.

Yet for all those physical virtues, arguably his most valuable attributes were his acute positional sense and composure.

In one-on-one confrontations with attackers, often he would leave a slight gap to entice the opponent to shoot where he wanted him to, and no matter how manically the action raged around him, he appeared to be in calm control.

Even Banks suffered aberrations, though, and one should coincide with the climax of a memorable 1962-63 campaign during which he had been instrumental in Leicester finishing fourth in the First Division and reaching another FA Cup final. This time at Wembley they started as favourites against a Manchester United side which had only narrowly avoided relegation, but Banks made three mistakes, all of which were punished, with Leicester eventually losing 3-1.

Overall, however, his development continued impressively and in April 1963 he had been rewarded by new England boss Alf Ramsey with his first international cap. That day he endured more Wembley heartache as England lost 2-1 to Scotland, but his competent performance saw him retain the gloves to face Brazil a month later. He eventually established himself as England’s number-one for practically all of the next eight years.

In 1964 Banks sampled success for the first time at club level when Leicester beat Stoke City in the two-legged final of the League Cup, a fledgling competition which had yet to capture the public imagination, but still the victory represented a notable achievement.

Back in the international arena, far greater glory was beckoning. Ramsey had vowed that England would win the World Cup on home soil in 1966, and they confounded majority opinion by doing so, with Banks exuding a colossal presence between the posts.

He preserved clean sheets as the team eased past Uruguay, Mexico, France and Argentina, was beaten once in the semi-final against Portugal (by the magnificent Eusebio from the penalty spot) but also pulled off a late match-winning save from Mario Coluna, and was blameless for the pair he let in during the dramatic final triumph over West Germany.

Shortly afterwards Banks was voted the world’s top goalkeeper and, not yet 30, he appeared to be an asset which any club would cherish. But Leicester City thought differently.

True, they were blessed with another marvellous custodian, the precocious teenager Peter Shilton, who had signalled that he would leave Filbert Street if he was not guaranteed regular first-team football. So the Foxes, against whom Banks had nursed frustrating financial gripes over several years, opted for the rookie, and in April 1967 manager Gillies declared, to the hurt of the 29-year-old England star, that his best days were behind him.

Most of the major clubs expressed an interest but then withdrew – Liverpool’s Bill Shankly reckoned his hands were tied by parsimonious Anfield directors – and at one point Banks was close to an attractive link-up with World Cup colleagues Bobby Moore, Geoff Hurst and Martin Peters at West Ham. Ultimately, though, the best offer was Stoke City’s £52,000 and he headed for the Potteries.

Banks might have wilted at what appeared to be a mystifying collective slight from football’s prime movers, but instead he flourished under the guidance of his new boss Tony Waddington and continued to burnish his reputation with England.

Indeed, Banks’ international stature reached a new zenith in the 1970 World Cup when he defied Pele with that gravity-defying save in a group match. The Brazilian was certain he had scored with a powerful downward header from Jairzinho’s cross, but somehow Banks propelled himself across his line, then twisted upwards to scoop the bouncing ball over the crossbar.

England lost that match but recovered to reach a quarter-final with West Germany in which Banks was unable to play because of a stomach upset. England went on to lose the match 3-2.

Banks, who was awarded the OBE that summer, returned to Stoke, where he joined with team-mates George Eastham and Jimmy Greenhoff in furnishing the Potters with a trophy.

In both 1970-71 and 1971-72 they reached FA Cup semi-finals, losing both times in replays to Arsenal. In 1972 there was glorious consolation as Stoke won the League Cup, with Banks tipping the balance in the semi-final against West Ham with a penalty save from Hurst, then standing firm against Chelsea’s glitterati – Peter Osgood, Charlie Cooke et al – as City shaded the Wembley final 2-1 to claim their first major prize in more than a century of trying.

For Banks, who had won six caps that term although the youthful Shilton and Ray Clemence were mounting challenges to supplant him at England level, there was further joy as he was named Footballer of the Year – the first keeper receive the accolade since his boyhood hero, Manchester City’s Bert Trautmann, in 1956. But 1972 ended with the most traumatic event of his life.

He was on his way home from the Stoke’s Victoria Ground when he was involved in a car accident which cost him the sight of his right eye. At the age of 35, most men would have accepted that their career was over but Banks fought back, evolving a new method for playing with one eye, based on geometry and the adjustment of angles.

Banks went on to play in the US for Fort Lauderdale Strikers, where he was voted the North American Soccer League’s goalkeeper of the year for 1977.

Banks returned to England in 1979 to put in a coaching stint with Port Vale, then briefly bossed non-League Telford United, who relieved him of team duties due to indifferent results and reduced him to selling raffle tickets before a public outcry secured an acceptable severance payment.

That was a poignant episode which left him disillusioned for a while but he recovered, later working in corporate hospitality, as a member of the Pools Panel, and for various charities.

It added up to a relatively low-key wind-down for the World Cup winner.

Was “Banks of England” the greatest net-minder ever? Few who witnessed him in his dazzling prime would argue otherwise.

Banks is survived by his wife, Ursula, whom he met while doing national service in Germany, and their children Robert, Wendy and Julia.

Gordon Banks, footballer, born 30 December 1937, died 12 February 2019

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments