Gloria Richardson: Civil rights activist who refused to compromise

Woman who fought against US segregation in the 1960s and help push through change

Gloria Richardson, who has died aged 99, was a civil rights activist and founding member of the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee (CNAC), which galvanised the local community of Cambridge, Maryland, in the fight against desegregation. Historian Paula Giddings described Richardson as “the first woman to be the unquestioned leader of a major movement and one of the first major leaders to openly question nonviolence as a tactic”.

Until 1964, many areas of public life in America were subject to segregation. Black people could vote but public spaces such as schools, restaurants and cinemas – even hospitals – were separated.

The racist Jim Crow laws enacted in the late 19th century had reversed former progress and enforced paradoxical “separate but equal” racial segregation on public transport and in public spaces. The CNAC brought these critical issues to the fore and contributed to the eventual passing of the Civil Rights Act.

Gloria St Clair Hayes was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1922 to Mabel and John Hayes. She grew up in Cambridge, Maryland, where her mother’s family ran a grocery store and funeral home. She was educated at Howard University in Washington DC, graduating with a degree in sociology in 1942.

On return from university, she married Harry Richardson, a teacher, and had two daughters. Her daughter, Donna, was a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee civil rights campaign group which inspired the creation of the CNAC. Chaired by Gloria Richardson and Inez Grubb, the CNAC held marches and demonstrations throughout 1962 and the following year, calling for desegregation and equality of rights.

Dr Peter Levy, author of Civil War on Race Street, said: “She defied the white power structure. They had always expected the black leaders to hold the peace, hold the order. They’re saying, ‘OK, if you guys agree to call off your protest, we’ll negotiate with you,’ and she said, ‘No, you’re not going to negotiate with us unless we’re on the streets, unless we’re marching’.”

Richardson, who was arrested three times, refused to condemn the violence that had become a feature of the demonstrations. She noted: “I am not saying that violence is necessarily the answer but I am not condemning the violence. It is a residue of frustration.” Thus, for her, the struggle had to take place both on the streets and in the council chambers.

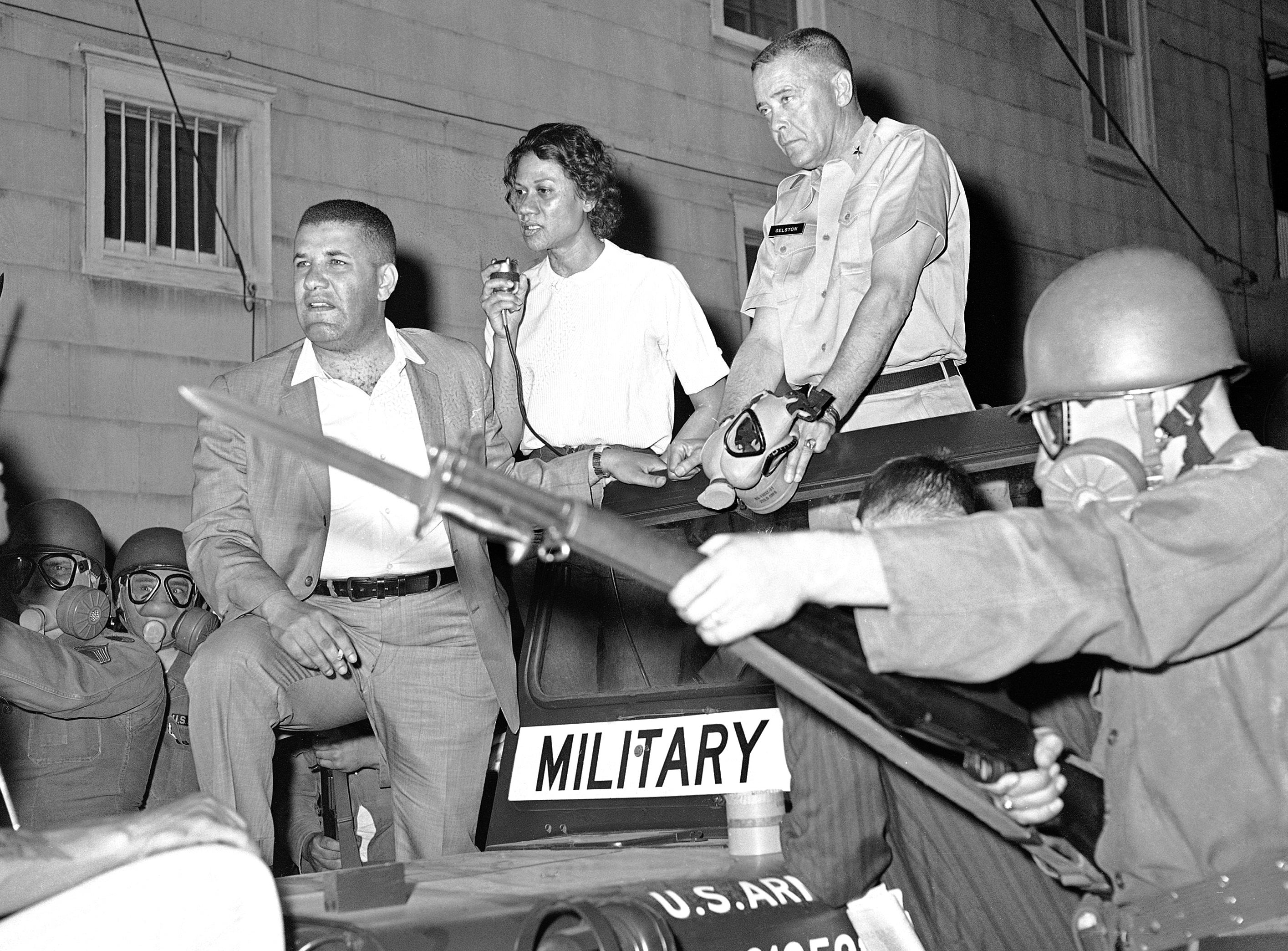

Commenting on a now famous photograph of her pushing aside a soldier’s bayonet, Richardson recalled: “We usually had something going on daily – demonstrations, marches, picketing – when we were out that day we heard what we thought were bullets and I was crossing to find out what happened.”

On 18 July, 1963, following a week of violent demonstrations, the state governor, J Millard Tawes, declared martial law and brought in troopers to quell the uprising. Just five days later on 23 July civil rights leaders, including Gloria Richardson, signed the Treaty of Cambridge, in the presence of US attorney general Robert Kennedy, calling for the immediate desegregation of all public spaces in Maryland.

At a national level, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August brought as many as 300,000 people to the capital, demonstrating for civil rights across the country. It was there that Martin Luther King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech, calling for equality and freedom.

Success for the campaigners came in the form of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, signed into law by president Lyndon Johnson on 2 July. This legislation prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, colour, religion, sex or national origin.

Richardson had lived since the mid-1960s in New York City, where had she worked with the Black Action Federation – a successor to the CNAC – and with Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited. Asked how she would like to be remembered, she replied: “I guess I would like for them to say I was true to my belief in black people as a race.”

She is survived by her two daughters, Donna and Tamara, from her marriage to Harry Richardson, whom she later divorced. She subsequently married Frank Dandridge, a photographer.

Gloria Richardson, civil rights activist, born 6 May, 1922, died 15 July, 2021

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments