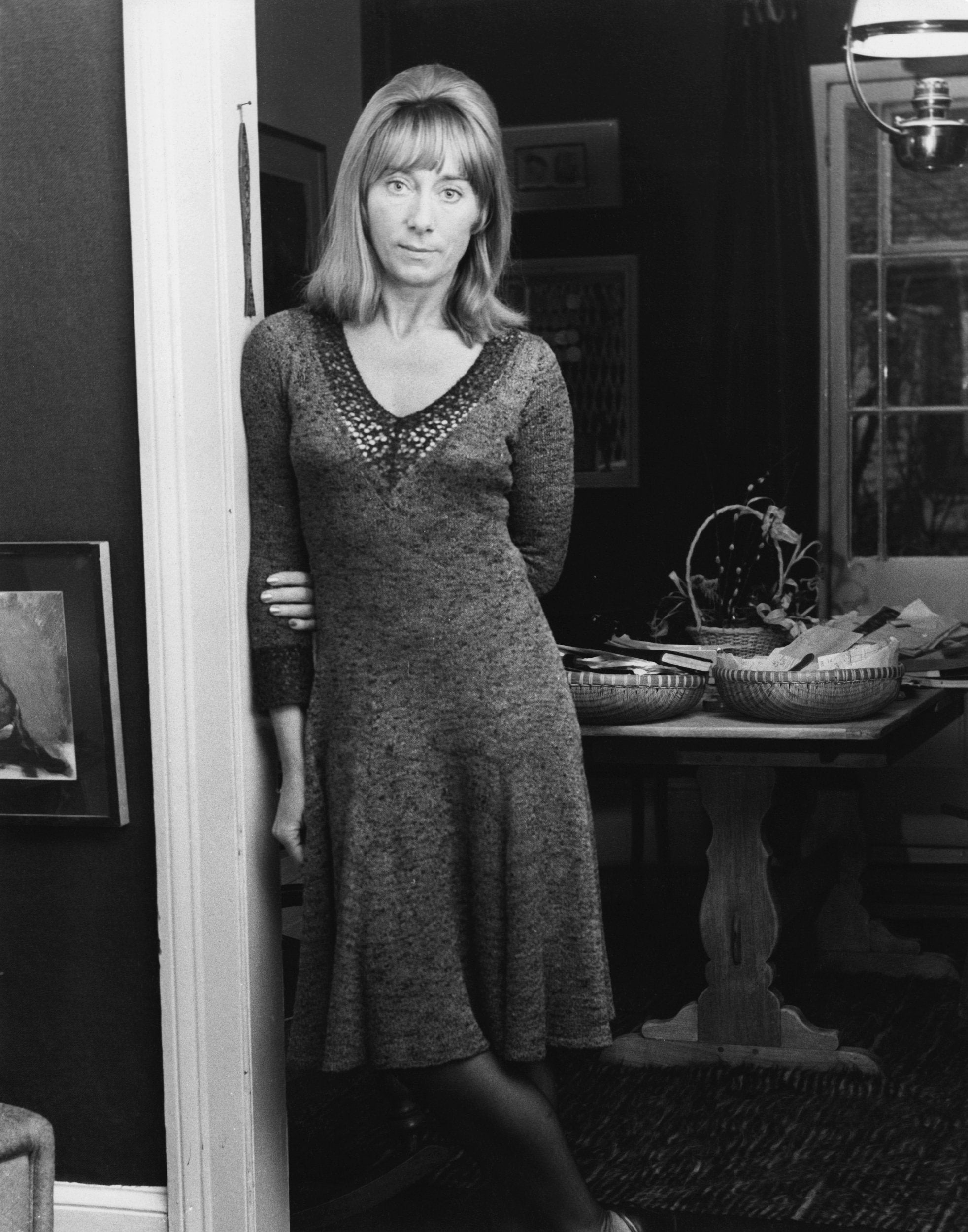

Dame Gillian Lynne: Ballerina and dancer who revolutionised choreography

Dame Gillian Lynne threw herself into dance during the war, and went on to inspire some of the West End’s biggest shows, including ‘Cats’ and ‘Phantom of the Opera’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In June, Dame Gillian Lynne was carried to a West End stage in a golden throne, surrounded by dancers from Cats, in a ceremony to mark the renaming of the New London Theatre as the Gillian Lynne Theatre.

It was a fitting tribute by the theatre’s owner, Andrew Lloyd Webber, to the dancer and choreographer whose genius helped him make shows such as Cats and Phantom of the Opera. As The Independent’s former arts editor David Lister put it, she “quite simply changed the way we think about dance”.

Lynne, who has died aged 92, was born in Bromley, Kent, to Major Leslie Pyrke and his wife Barbara. Though Barbara (nee Hart) was a keen amateur dancer, it was not she who first noticed her daughter’s talent – it was the family doctor.

When told that her daughter lacked focus and was prone to fidgeting, the doctor suggested that rather than a problem child, Barbara had a dancer on her hands.

Lynne – the stage name she picked up later in life – duly began her formal dance education at the Miss Madeleine Sharp’s Ballet Class for Young Ladies in Bromley.

She once said: “I felt I was only my real self when I was dancing or in the theatre or with my music – all the rest of the time I was or felt like a shadow, a restless shadow wandering aimlessly waiting for life to be breathed into it to give it a real form.”

In 1936, aged 10, Lynne won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Dance. Three years later, her mother was killed in a car crash.

In A Dancer in Wartime, her autobiography, published in 2011, she recalled the moment she heard the news: “I heard an extraordinary sound: a sharp deep boom. It was very strange and to this day I cannot explain it, but in that instant I understood that my childhood had ceased.”

Lynne focused on her dancing but the war took hold and she had to forfeit her place at the Royal Academy when she was evacuated to Somerset.

In 1944, back in London and dancing for the English dancer Molly Lake, Lynne was headhunted by Ninette de Valois to join her company at Sadler’s Wells. Though the war continued, Lynne wrote of the time, “Bombs, danger, ruined streets, no food to speak of – these were commonplace to us. The discipline of the dancer was such that we seemed to sail through it.”

In 2013, she recalled, “I had very poor schooling because of the war and the only thing I was any good at was divinity.”

When she was playing an angel in the ballet Job for De Valois, she said: “My talent for religious thinking led me to become so carried away ... that Ninette stopped the rehearsal and yelled ‘Lynne! There’s no need to give us your entire soul, a simple smile will do’.”

She danced her first solo at Covent Garden in 1946, in The Sleeping Beauty, which also starred Margot Fonteyn. Lynne dedicated her performance to her mother. “We were alone, entering the world she had always wanted for me, and I offered up my dance to her,” she said.

Lynne danced with the Sadler’s Wells Ballet until 1951, when she became star dancer at the London Palladium. Around the same time she was cast opposite Errol Flynn in the film The Master of Ballantrae (1953). Diversifying into choreography, Lynne would go on to work with the Royal Opera House, the Royal Shakespeare Company and English National Opera. She worked on more than 60 West End shows, however she is probably best known for her work with Andrew Lloyd Webber on his musicals Cats, Phantom of The Opera and Aspects of Love.

Despite having knee and hip surgery, Lynne continued to work well into her eighties, choreographing the 25th anniversary production of Phantom at the Albert Hall. Two years later, aged 87, she directed and choreographed Dear World at the Charing Cross Theatre.

Throughout her career, Lynne’s work was nominated for and won an enormous number of awards, including the Olivier Award in 1981, for outstanding achievement of the year in musicals, for Cats. She won a second Olivier, the Special Award, in 2013. She was appointed in the 1997 and made a dame for her services to dance and musical theatre in 2014.

Lynne was married twice. She met her second husband, actor Peter Land, aged 65, who survives her, when she directed him in a production of My Fair Lady. They married in 1980. She later joked, “I suppose I’m quite proud of being able to hang on to someone 27 years younger than myself.”

Dame Gillian Lynne, dancer and choreographer, born 20 February 1926, died 1 July 2018

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments