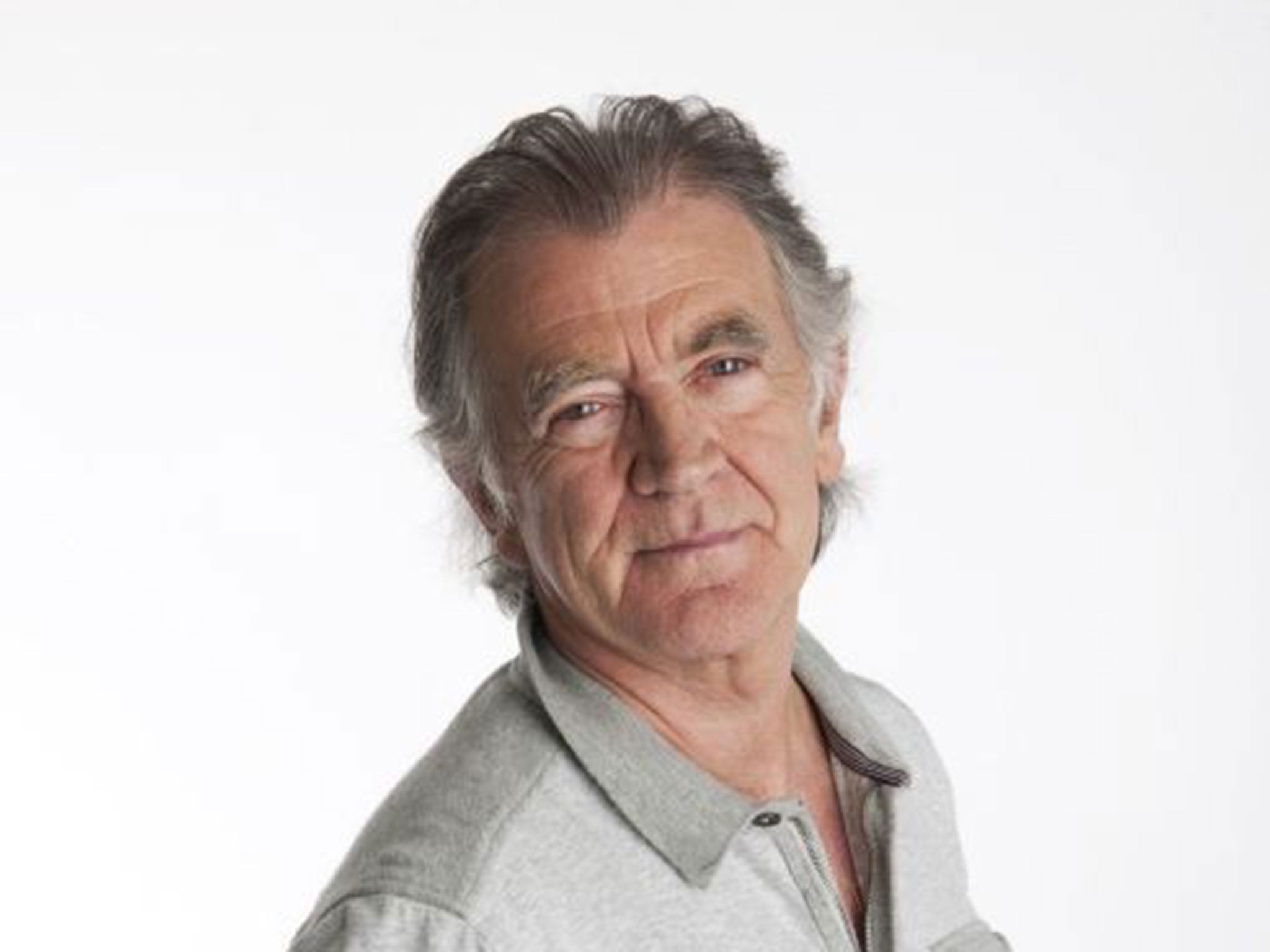

Gerry Anderson: Broadcaster who became much-loved in Northern Ireland but came unstuck when he moved to Radio 4

Listeners objected in their thousands to Anderson Country. ‘I was destroyed,’ he admitted

Gerry Anderson had the distinction of being among the most popular broadcasters in one country and one of the most reviled in another. In Northern Ireland he was regarded as an entertainer at once exceptionally clever and quick-witted, self-deprecating and with his own brand of charming unpredictability. But in the mid-1990s, when transplanted to Britain in attempt to give new reach to Radio 4, he was hounded off the airwaves by a deluge of criticism of programme content, his accent and his style in an extraordinary display of listener power.

His daily show, Anderson Country, was described as one of the most vilified programmes in the BBC’s history of the BBC. Sorely wounded – “I was destroyed,” he admitted – he returned within a year to his home city of Londonderry. There he picked himself up and quickly resumed his former status as something close to a national treasure, his almost entirely unscripted shows providing the ideal vehicle for his spontaneous badinage.

The contrast was remarkable between his rejection in London as an undesired provincial and his popularity on the other side of the Irish Sea, where he was widely regarded as something special. When he first came to the attention of the BBC’s London bosses and brought to London to front his own show it seemed like the opportunity of a lifetime. But the whole thing quickly became a nightmare.

Born in Derry in 1944, he was educated by the Christian Brothers, some of whom, he said, beat him black and blue. “Like everybody else at school in those days we were battered about,” he told his listeners. Teachers had a republican slant, “and would try to turn little boys into little republicans.” This, he said, resulted in some of his fellow pupils ending up behind bars.

Released from the Brothers’ clutches, he became something of a drifter. After a short and unsuccessful career as an apprentice toolmaker – he was sacked, he said, “for bad attitude” – he went on the dole in Derry, traditionally an area of high unemployment. According to his own description of the next phase of his life: “Retired to bedroom and emerged three years later as a rock and roll guitar player; played in bands and lived in England, Dublin, Canada and America until I got too old to stay up three days in a row; dropped out of rock and roll and went to university for five years.”

The rock scene, as portrayed in his memoirs, was less than glamorous: “Many a day was spent staring penniless through the scuffed windows of back-street boarding houses avoiding shrill, fat landladies, subsisting on a balanced diet of milk and Mars bar, waiting for news of the next gig.”

After university he worked as a teacher, assistant social worker and community magazine editor before more or less accidentally stumbling into broadcasting, eventually getting his own show on BBC Radio Foyle and Radio Ulster. He was a natural, attracting ever larger audiences and collecting a bevy of awards.

This brought him to the notice of Radio 4, whose heads calculated that his ready wit and easily self-confidence could broaden its audience. They were wrong. It quickly became clear that what was conceived as a bold new departure was a disaster, since the qualities that had made Anderson such a success in Northern Ireland repelled many Radio 4 listeners.

He was labelled Britain’s most derided broadcaster. Gone was his freewheeling unscripted humour; instead came shows featuring phone-ins and light items discussing the value of Best Kept Village competitions, and whether children should be allowed in pubs.

Newspaper columnists gave it a pasting: cheap, superficial, unbelievably dreadful and fatuous were some of the adjectives applied in the show’s first few weeks. The most telling attacks came from the public.

Chris Dunkley, presenter of the Feedback programme, summed up: “We had an enormous postbag. People really were in high dudgeon about it. They were saying, ‘Stop treating us as a social experiment. We’ve heard John Birt saying that the BBC mustn’t super-serve the middle classes, but just leave us Radio 4.’ They objected to the patronising tone that they should accept something different.”

Anderson’s performance deteriorated as his anxiety levels grew. “I began to lose confidence in myself,” he remembered. “Every day it felt like I was on trial. It got to the point where I was afraid even to speak in case I mispronounced a word or said anything even vaguely controversial or amusing. If I did I knew someone would write about it and call me a lamebrain or an airhead. I’m not a journalist and never have been and I was being asked to do journalist-type things which I wasn’t comfortable with.” His spontaneity went and his contract was ended early, by mutual agreement.

His later analysis of what went wrong centred not on BBC management but on “the core listenership of Radio 4 – about 15 per cent – that doesn’t listen to anything else,” he wrote. “They feel let down by the empire, the government, the state and the education system. They feel that the last bastion of quality is Radio 4, and when that changes they have nowhere else to go. So they campaign to get things back to as they were.”

Returning to Northern Ireland he was given his old show back again and, back in his natural habitat, gave every appearance of putting behind him his bruising encounter with middle England.

Gerald Michael Anderson, broadcaster: born Derry 28 October 1944; married Christine (one daughter, one son); died Belfast 21 August 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments