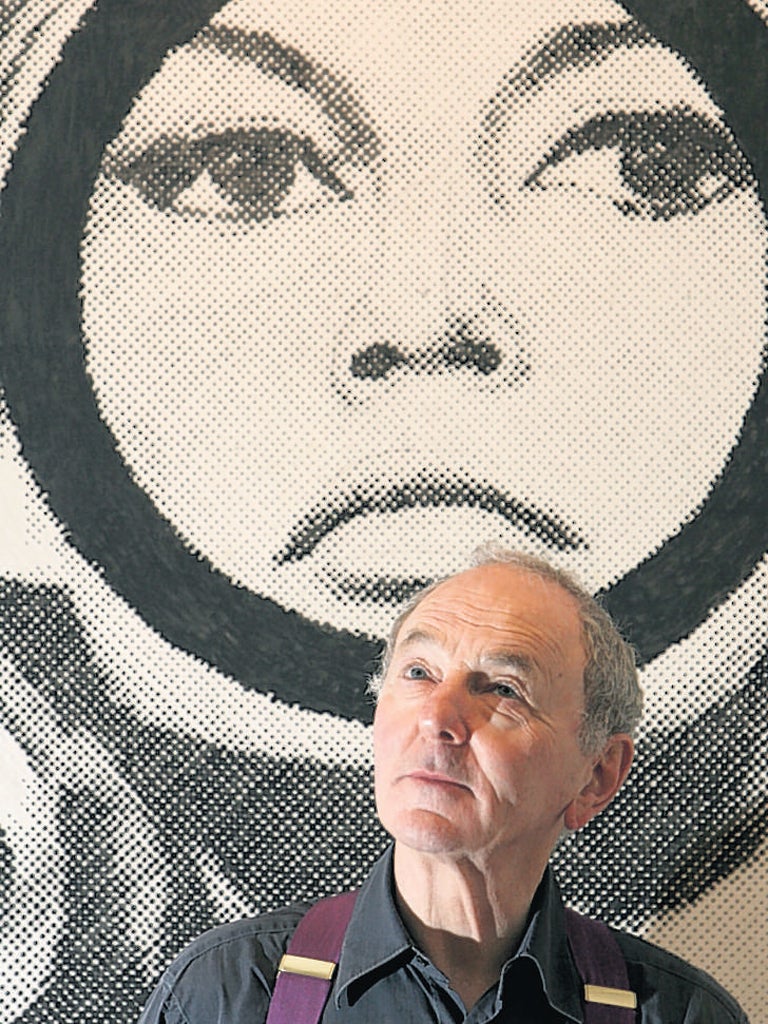

Gerald Laing: Artist whose work encompassed Sixties Pop Art and figurative sculpture

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Gerald Ogilvie Laing of Kinkell was unquestionably one of the late 20th-century British sculptors whose work will be recognised and valued for centuries to come. "He was a great figure in the heady world of the international Pop Art scene," James Holloway, Director of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, told me. He later became a figurative sculptor of great distinction; two of his heads will be on display in the Gallery when it reopens on 1 December.

Laing was the antithesis of the caricature of a wayward, disorganised artist. He went about his calling with the discipline and efficiency of a Sandhurst-trained regular military officer, which he had once been. In 1994, my wife, Kathleen, deeply impressed by Laing's contribution as a fellow commissioner of the Royal Fine Art Commission for Scotland, asked him to sculpt my head in bronze. The venue had to be a spot in the Parliamentary Precinct. The Sergeant-at-Arms went to some trouble to secure a room. Enter Laing. "This will not do at all," he said. "The light is totally unsatisfactory." It looked as if the commission was cancelled. What did Laing want? "A room with the early morning light streaming through the window, overlooking the Thames."

A less forceful artist would have been fobbed off. But Laing, always determined, persuaded/cajoled the Sergeant into allowing us to use a Commons Committee room. I had to be "on parade" at 8am till 9am for successive mornings. Of chatter there was little: Laing's modus operandi was intense concentration. He encouraged me to bring my MP's morning mail. Every so often, he would bark "attention", and after a few minutes "at ease". Later in the day Bob Sheldon, then chairman of the Public Accounts Committee, whose room was just along the corridor, and other colleagues, would gingerly lift Laing's dust cover and take a peep. They discerned a supremely methodical artist.

Gerald Ogilvie Laing was born the son of an officer, Gerald Francis Laing, whom he respected as a no-nonsense disciplinarian. After success at Birkhamsted School, and greater success at Sandhurst, Laing was commissioned to the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers. Within months he became bored and wrote to his commanding officer that he wished to resign his commission. The letter was ignored. Laing wrote again. This time he was summoned to the CO, who told him, "Laing if you write letters like this, you will have no future in the army!" It took him five years to extricate himself. From 1960 to 1964 St Martin's School of Art in London enjoyed the unusual experience of teaching a highly organised young officer.

From 1964 to 1969 Laing lived in New York, exhibiting in the Richard Gray Gallery in Chicago and in Los Angeles. His work, inspired by the pop scene and influenced by Andy Warhol, featured in selected group exhibitions at, among others, the Albright Knox Gallery in Buffalo, in the Museum of Contemporary Art in Nagaoka, Japan, in the San Francisco Museum of Art and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Andy Warhol was one of his friendships and lifelong influences; his bronze portrait of Warhol in 1990 is but one of his wonderful likenesses – others included Air Vice-Marshal Johnnie Johnson, Sir Charles Fraser, Alexander Goulandris and his son Titus, aged two.

Laing was not only a sculptor but a painter and weaver of tapestries. He approached Henry Moore to ask him if he could use his drawings as a basis for tapestries. I believe it is the only occasion Moore gave any such permission, since he was impressed by Laing's application in perfecting the art.

Laing believed that portraiture is not simply the imitation of nature. He told me, somewhat dauntingly, that "it is the substitution of sculptural metaphor for the objective reality of the sitter." He explained that this metaphor is achieved by the selection and reinvention of the natural forms which constitute the physical appearance of the sitter. Each form should be, he argued, in itself intriguing and original, and could be seen as separate and abstract: taken together all of them compose into a human presence – as Laing put it, much as "a newspaper photograph closely inspected disintegrates into a series of dots, but re-forms into a coherent image when seen at a distance."

Among Laing's major public commissions were the Callanish at Strathclyde University, the frieze of the Wise and Foolish Virgins at No 3 George Street Edinburgh, the Fountain of Sabrina at Broad Quay House, Bristol, the Conan Doyle Memorial and Tanfield House Axis Mundi, Edinburgh, the Bank Station Dragons in London, the four figures on Rowland Hill Gate at Twickenham and the Fifth Fusilier Memorial at Badajoz in Spain, which gave Laing special pleasure since he'd been a fusilier 40 years earlier.

Dons at my own college, King's Cambridge, told me how impressed they were by Laing's exhibition, which they hosted, of anti-war paintings inspired by Iraq. "Never," he blazed, "should MPs on green benches send other people's fathers, brothers, sisters, and sons to war unless there is a clear military objective! It was absent in Iraq." He also made a recent series of paintings featuring the singer Amy Winehouse.

Laing's workplace and physical and spiritual home for 40 years was Kinkell Castle in the Black Isle of Ross & Cromarty, where he was chairman of the local Civic Trust. Determined to stay there during lingering cancer, despite its spiral staircases, Laing was visited by friends from Britain and the US who had travelled to say their goodbyes to this remarkable artist. His book Kinkell: the Reconstruction of a Scottish Castle would be an ideal present for any architecturally minded relative or friend.

Gerald Ogilvie Laing of Kinkell, soldier and artist: born Newcastle upon Tyne 11 February 1936; married 1962 Jennifer Anne Redway (one daughter), Galina Vassilovna Golikova (two sons), 1988 Adaline Havemeyer Frelinghuysen (two sons); died Kinkell, Ross & Cromarty 23 November 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments