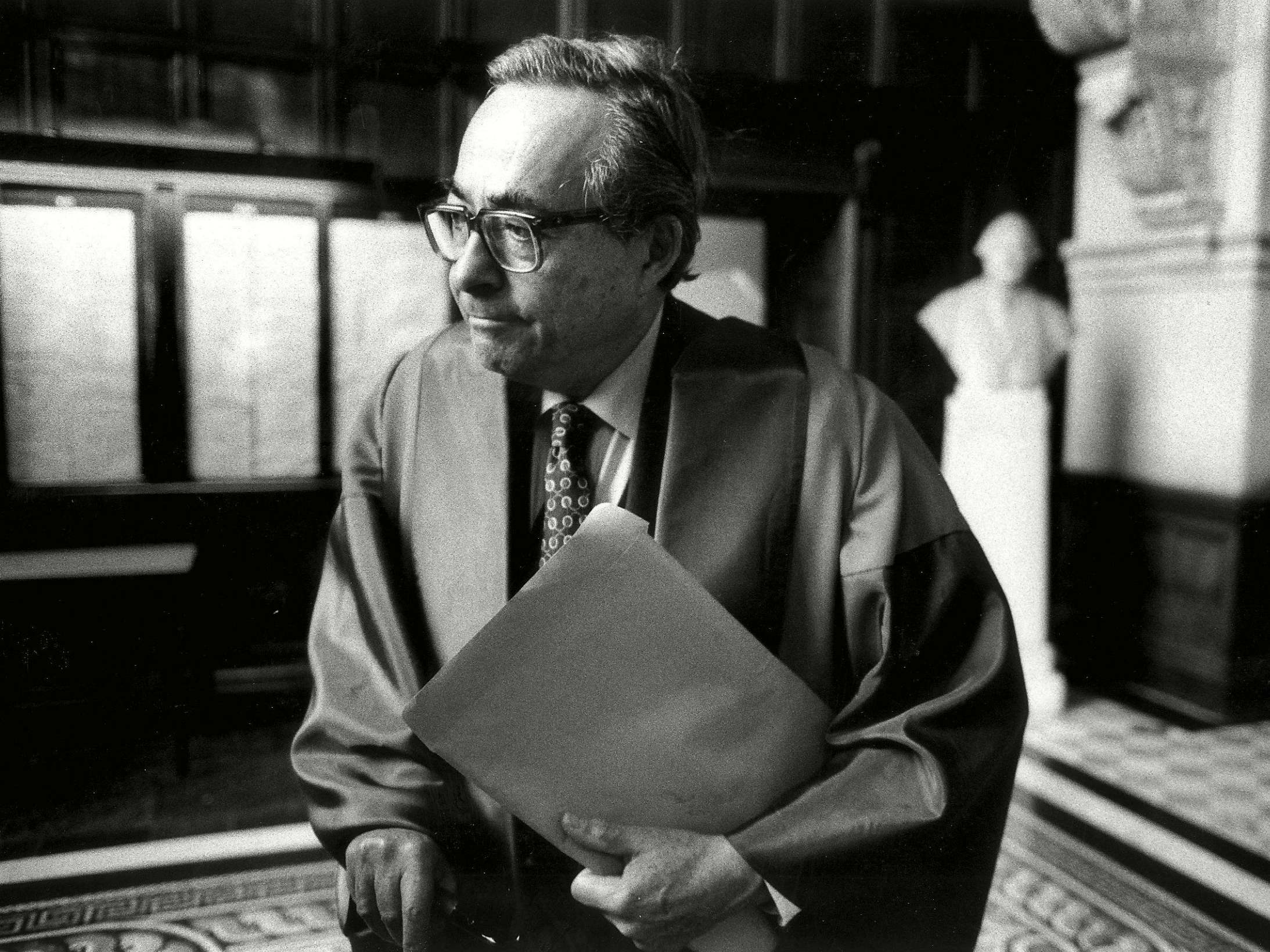

George Steiner: Literary critic whose influence went well beyond academia

A scholar and polymath of rare depth and range, he was a staunch defender of ‘high’ literature and philosophy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.George Steiner was a renowned literary critic who trained his formidable mind on literature that spanned millennia, from the ancient classics to works of modern masters, exalting European humanism even as he grieved its inability to spare the world from atrocities such as the Holocaust.

Steiner, who has died aged 90, was the rare literary critic whose scholarship was celebrated and debated far beyond the silence of university libraries.

He spent the greater part of his career teaching at the University of Cambridge, but he also was chief critic from 1966 to 1997 at The New Yorker. Such was the esteem surrounding Steiner that he drew comparisons to Harold Bloom, the late Sterling professor of the humanities at Yale University whose bestselling works sparked impassioned public debate about the value of his beloved western canon.

Over more than a half-century of scholarship, Steiner hopscotched from the Greek myth of Antigone to the works of Shakespeare, Coleridge, Proust and Borges. A critic who first made a name for himself analysing Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, he later championed Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance before it became a classic of the countercultural era.

In the background, if not the foreground, of all Steiner’s work was the devastation of the Holocaust, which he survived by fleeing Paris with his Viennese-born Jewish parents shortly before the Nazi occupation in 1940. The proximity of art to murder – “Europe,” Steiner once observed, “is the place where Goethe’s garden almost borders on Buchenwald” – was a theme that ran throughout his entire oeuvre.

His works of criticism included Tolstoy or Dostoevsky (1959), In Bluebeard’s Castle: Some Notes Towards the Redefinition of Culture (1971), After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation (1975) and Grammars of Creation (2001). But he became particularly known for works such as Language and Silence: Essays on Language, Literature, and the Inhuman (1967).

“The house of classic humanism, the dream of reason which animated western society, have largely broken down,” he wrote in that volume. “We know now that a man can read Goethe or Rilke in the evening, that he can play Bach and Schubert, and go to his day’s work at Auschwitz in the morning.”

In his devotion to high literature, high philosophy and any other pursuit that could be classified as high rather than low, Steiner was resolute. “We live in a time when even professors claim not to see much of a difference between Pushkin and Letterman,” he said in 1998. “There is a terrible fear of being found ‘literary’.”

Francis George Steiner was born in Paris in 1929. His father worked for a bank and counted among his friends the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. The future scholar credited his mother with instilling in him the fortitude to overcome a birth defect that made his right arm nine inches shorter than the left.

He taught himself to write with a fountain pen but later found it more convenient to type his books on an Olivetti typewriter and later an IBM Selectric.

Asked whether he read anything “frivolous” in his boyhood, Steiner quipped: “Moby-Dick.” He told The Independent in 2003 that he began studying Greek at the age of six to discover the end of Homer’s Iliad.

Having foreseen the intensifying persecution of Jews in Nazi Europe, his father moved the family to the United States when Steiner was 11. He stopped using the name Francis at that time and became a US citizen in 1944. Steiner received a bachelor’s degree from the University of Chicago in 1948, a master’s degree from Harvard University in 1950 and a doctoral degree from the University of Oxford, where he was a Rhodes scholar, in 1955. After his dissertation was at first rejected, he worked briefly for The Economist magazine before beginning his academic career.

He taught at several US universities but made his life in Europe, he said, because his father had said that if he did not, then Hitler would have succeeded in his quest to rid Europe of Jews. Steiner had a long association with the University of Geneva in Switzerland, in addition to his post at Cambridge.

He ventured into fiction with works including the novella The Portage to San Cristobal of A.H. (1981), in which he imagined that Hitler had survived the Second World War and escaped to Latin America, where he was discovered by Nazi hunters.

Among Steiner’s later books were the memoir Errata: An Examined Life (1998) and My Unwritten Books (2008), about the works he would have liked to write.

His wife, the historian Zara Alice Shakow, whom he married in 1955, died 10 days after her husband, on 13 February. He is survived by his two children.

George Steiner, writer and critic, born 23 April 1929, died 3 February 2020

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments