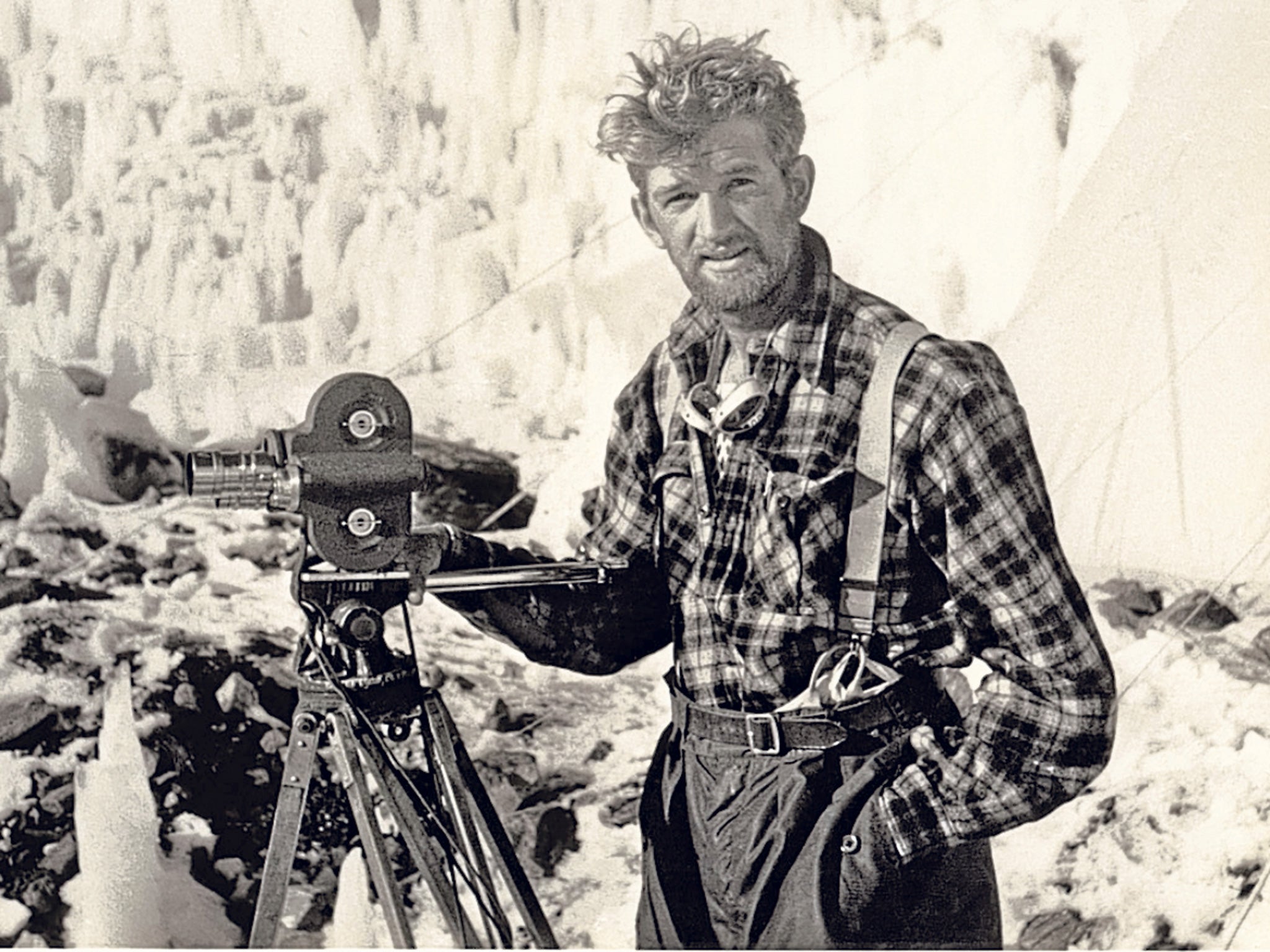

George Lowe: Last surviving member of the 1953 expedition that conquered Mount Everest

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.If George Mallory's off-the-cuff justification for climbing Everest, "because it's there", are the best known words in mountaineering, Edmund Hillary's less enigmatic summary of the first ascent, "we knocked the bastard off", must rank a close second. Hillary never intended the remark for public consumption. He delivered the words to his fellow New Zealander and close friend George Lowe some 150m above the South Col on 29 May 1953. Lowe had climbed to meet Hillary and Tenzing Norgay as they descended the mountain, but neither he, nor the rest of John Hunt's team waiting below, knew the whether the pair had reached the summit.

"They were moving fairly rapidly – the only tiredness showed in their slightly stiff-legged walking as they cramponed the last part of the couloir," Lowe recalled. "I crouched, back against the wind, and poured out the thermos contents as they came. Ed unclipped his mask and grinned a tired greeting, sat on the ice and said in his matter-of-fact way, 'Well, George, we knocked the bastard off!' It was not quite matter-of-fact – he was incredulous of what they had done."

Lowe felt the need to put the record straight in the 1990 Alpine Journal: he said it meant no disparagement to Everest and was intended for his ears alone. In New Zealand slang, big mountains were referred to with admiration as "big bastards", said Lowe. "Ed had to live with the fact that I told the BBC what he said on meeting me, and he has never forgiven me for it!"

Lowe's sense of fun is in play, and even were it not, Hillary had little to forgive; Lowe had played a major part. An accomplished ice climber, he had spent 11 days at around 7,000m, battered by high winds, pushing the route up the Lhotse Face towards the South Col. Hunt described it as "an epic achievement of tenacity and skill".

On 28 May Lowe had led the way up from the South Col. With Lowe, as well as Hillary and Tenzing, were Alf Gregory and Ang Nyima. At 8,340m they picked up a cache of gear left, after a gruelling carry, by Hunt and Da Namgyal. Hillary was carrying around 63lb, Lowe and Gregory 50lb each and the two Sherpas 45lb each – all way over the 15lb reckoned to be a good load at such an altitude. This Herculean effort succeeded in placing a camp at about 8,500m, from where Hillary and Tenzing would go for the top.

Wallace George Lowe was born in the farming community of Hastings, North Island, the seventh of eight children, and seventh child of a seventh child. His father was a fruit grower and kept bees. He got his queen bees from the Hillary family in Auckland,

The young George hardly seemed destined to be a climber. At nine he had broken his left arm; it would not mend and had to be realigned seven times. It remained bent and virtually without muscle for the rest of his life. Added to this, he had an early fear of heights. He attributed his embrace of mountaineering to his determination to face up to his weaknesses.

Climbs with Hillary and others in the Alps led to the Himalaya in 1951, where he and three companions made the first ascent of Mukut Parbat. At the village of Rhaniket they picked up their mail, including a telegram from Eric Shipton inviting two of them to join an expedition to Everest's south side. The telegram "turned four amiable New Zealanders, relaxing in the hill station lounge, into four tense tigers, caged, self-seeking, eying each other with jealousy," Lowe wrote in his readable memoir Because it is There (London, 1959). But he and Ed Cotter were broke and had to watch as Hillary and Earle Riddiford departed.

A year later, thanks to Hillary's recommendation, Lowe was invited by Shipton to join the British expedition to Cho Oyu (8,201m), a tough rehearsal for the 1953 attempt on its neighbour, Everest. It remained unclimbed but Lowe and Hillary took consolation in an outstanding first crossing of the Nup La pass from which they descended secretly into Tibet. The two colonial boys had earned their ticket to join the chaps next year.

Lowe had trained as a teacher and was working in the primary school where he had been a pupil. He had been given leave for his Himalayan trips in 1951 and '52, but a third time he was refused, so he resigned.

Though Lowe would later return to teaching, Everest opened a second profession, photographer and film-maker. Lowe had been a keen "stills" amateur and when pneumonia rendered Tom Stobart, the expedition cameraman, unable to work at altitude, his movie moment arrived. Entering the Khumbu Icefall it was the first time he had held a ciné camera; action sequences he shot contributed greatly to the success of the Oscar-nominated The Conquest of Everest.

These credentials, together with a familiarity with crevasses, led to his being invited to join the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, which occupied him for three years. In a tracked Weasel vehicle called Wrack and Ruin he made the 2,158-mile crossing in 99 days, uniting with Hillary at the South Pole on 19 January 1958, his fellow Kiwi having approached from Scott Base in the opposite direction.

In 1959 Lowe returned to education, first at Repton School, Derbyshire, and then from 1963 at the Grange School in Santiago, where he became headmaster. In 1962 he had married Hunt's daughter Susan and their three sons were born in Santiago. The family returned to the UK in 1973 – the year of the military coup in Chile – after which Lowe worked as a schools inspector.

Like Hillary he felt a deep commitment to the Sherpas and in 1989 helped found the UK arm of Hillary's Himalayan Trust, funding schools, health services and other projects. The work was shared by his second wife Mary, who continues as secretary.

Lowe, the last surviving member of the 1953 climb, has been described as the "forgotten hero" of Everest. It is unlikely he minded. Though witty and amusing company, he shunned the limelight and expressed relief he was not in the summit party. "Ed Hillary was the right one. I wouldn't have had the diplomacy that he had," he said.

Wallace George Lowe, mountaineer, photographer and teacher: born Hastings, New Zealand 15 January 1924; CNZM, OBE; married 1962 Susan Hunt (marriage dissolved; three sons), 1980 Mary Richards; died Ripley, Derbyshire 20 March 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments