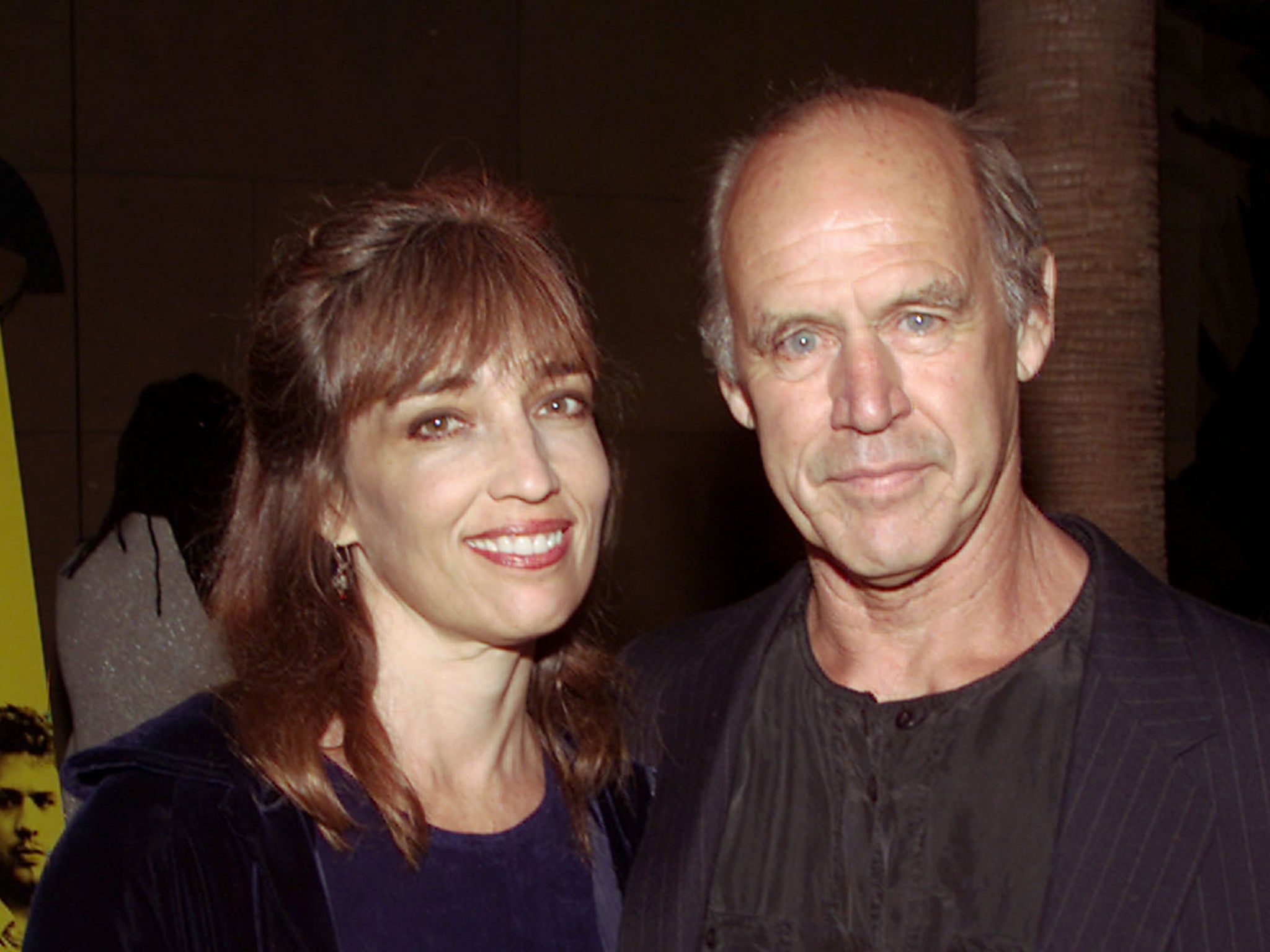

Geoffrey Lewis: Character actor whose wide-eyed stare and sinister chuckle made him perfect as disturbing and scene-stealing villains

He was most familiar as a regular player in Clint Eastwood’s films

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Among the most prolific of latter-day Hollywood character actors, Geoffrey Lewis was unmistakeable with his wide-eyed stare and sinister chuckle. Gaining in visibility during the 1970s wave of tough, realistic Westerns featuring younger protagonists than previously in the genre, such as Robert Benton’s Bad Company (1972), he was most familiar as a regular player in Clint Eastwood’s films, generally made by the star’s Malpaso Company.

Often playing subordinates with differing degrees of loyalty, Lewis on occasion resembled a rodent granted human form. He would smile with his mouth, but his flickering eyes would tell a different story. Possessing a lightly pitched, vaguely countrified voice, he was a master at stealing scenes while skulking in backgrounds, chewing tobacco, polishing his gun or shooting threatening looks. With his dark back-combed hair, high forehead, wide mouth turned downwards and prominent jowls, at times he looked similar to another lugubrious Geoffrey, the very British Mr Palmer.

After spending his early childhood in Rhode Island, from the age of 10 he lived in Wrightwood, California – one schoolfriend from Victor Valley High School recalled him joking around by assuming a Southern accent, even at that stage. His earliest acting excursions were at the Plymouth Theater in Massachusetts.

Starting as he meant to go on, Lewis was in Bonanza (1970) as a townsman recognising a purported rain-maker as a mountebank. A science-fiction entry in the series The Name Of The Game, “LA 2017” (1971), was an early directorial credit for Steven Spielberg. Twice, Lewis was in third-villain-from-the-left mode in Mission: Impossible (1972), on the second occasion saying to Peter Graves “Does it hurt? That’s tough” while tying him up.

Lewis’s first film with Eastwood, who starred and directed, was High Plains Drifter (1973), unshaven and at his most wide-eyed as an outlaw just out of prison. He was then a partner in crime to the star, and getaway driver to Jeff Bridges in drag, in Thunderbolt And Lightfoot (1974); writer-director Michael Cimino returned Lewis to a Western setting in the financially calamitous Heaven’s Gate (1980).

For Eastwood’s former collaborator Sergio Leone, Lewis was a villain posing as a barber at the end of My Name Is Nobody (1973). Another spaghetti western to feature Lewis was Sella D’Argento (1978), directed by horror specialist Lucio Fulci. For John Milius, who had co-written Eastwood’s first two Dirty Harries, he appeared unexpectedly well-groomed as one of the gangsters in Dillinger (1973). Milius smartened him up again as Roosevelt’s Consul General in Morocco in The Wind and The Lion (1975). Off-screen, Lewis and the writer-director shared a fondness for firearms.

The Great Waldo Pepper (1975) cast Lewis as a government man temporarily halting Robert Redford’s airborne exploits. A 1975 episode of Starsky and Hutch, among villains who turn Hutch into a heroin addict, was excluded from the BBC’s broadcasts of the series. He played a psychologist in Michael Mann’s The Jericho Mile (1979), a prison-set drama uncompromising by television standards.

For all that Lewis’s redneck villains could be deranged and menacing, arguably his most disturbing rural role was a gravedigger in the TV version of Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot (1979), particularly when seen in a rocking chair after having fallen victim to a vampire. Very different was Every Which Way But Loose (1978), where he was the gormless Orville, manager to Eastwood’s bare-knuckle boxer Philo Beddoe. Orville took second place in sidekick duties to Clyde the orang-utan.

Eastwood, Lewis and leading lady Sondra Locke returned to their roles for Any Which Way You Can (1980), and in quick succession reteamed for circus tale Bronco Billy (1980). Directing, Eastwood cast Lewis as Locke’s no-good husband, winding up in a psychiatric home. He also did an episode of BJ And the Bear (1980), a series whose premise was clearly appropriated from the Which Way films.

Continuing to work hard, Lewis, coincidentally or otherwise, was seen supporting action stars who had similar Republican or rightist politics to Eastwood, but not quite the same gravitas. He was an unscrupulous lawyer in the unpleasant Charles Bronson vehicle 10 To Midnight (1983), guested in Chuck Norris’ TV series Walker, Texas Ranger (1994), and worked with Mel Gibson in The Man Without A Face (1993) and Maverick (1994).

Increasingly allowing his baldness to be seen, his TV parts included The A-Team (1984), as a bad guy harassing a religious sect: Magnum, PI (1986), playing older than his years as a murderous circus act called Gus the Geek: and The X-Files (1999), as a photographer whose subjects drop dead immediately afterwards. Eastwood used him again in Pink Cadillac (1989), and as an exploited inventor surrounding himself with flies, one of the eccentric inhabitants of Savannah in the altogether higher-profile Midnight In The Garden Of Good And Evil (1997).

Lewis had a second line in intoning short stories against a musical accompaniment, beginning in 1970 with an act called The Great American Entertainment Show, and from 1984 as part of a band, Celestial Navigations, billed as “word/jazz storytellers”. Allowing him freer reign with accents and facial expressions, and sometimes written by himself, the stories often had a spiritual aspect; Lewis’s activities in that area led him to become a Scientologist, maintaining that it had aided his career choices.

His association with the movement dated back to an obscure short, Freedom (1970). In Double Impact (1991) he was the foster father of Jean-Claude Van Damme. In real life his daughter Juliette achieved prominence in the early 1990s. Like him she has musical inclinations, which she has latterly focused on, as well as a belief in Scientology. They acted together in The Way Of The Gun (2000) and Blueberry (2004).

Geoffrey Bond Lewis, actor: born San Diego, California 31 July 1935; married 1973 Glenis Batley (divorced 1975), 1976 Paula Hochhalter (five daughters, four sons); died Los Angeles 7 April 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments