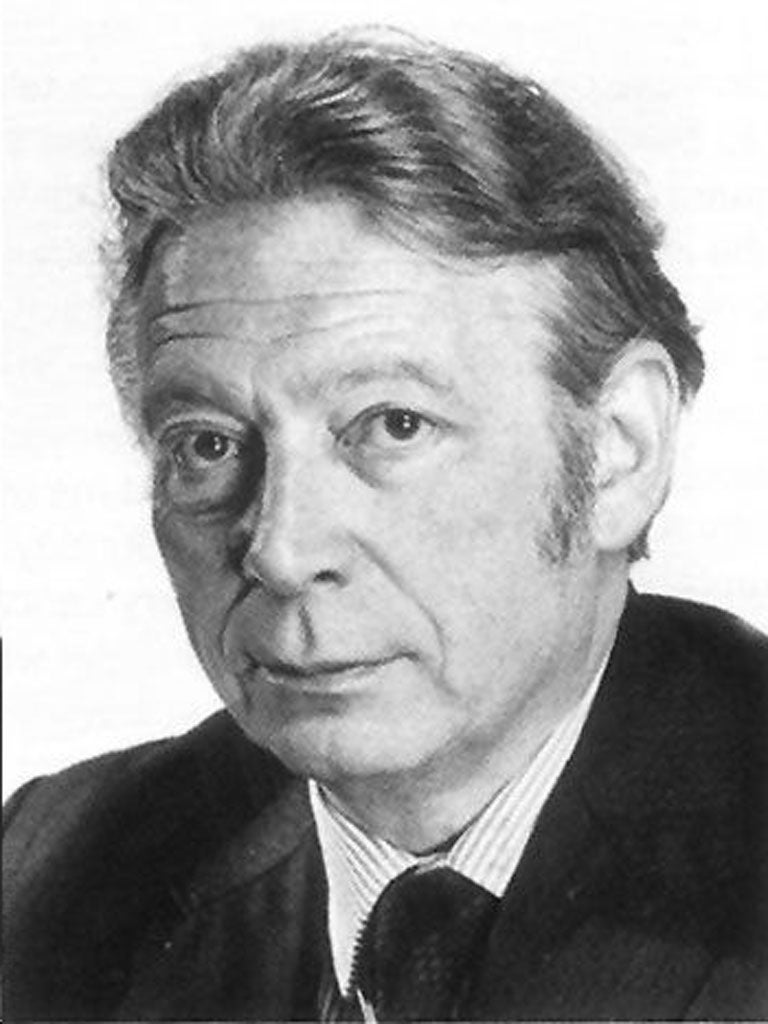

Geoffrey Goodman: Industrial and political journalist respected and admired by Left and Right

He regarded Robert Maxwell as a monster and regretted not resigning earlier from the ‘Mirror’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.By the time he retired from the Daily Mirror in 1986 Geoffrey Goodman had become a Fleet Street institution. His 18 years on the paper, as Industrial Editor, won him the respect of colleagues, politicians and both sides of industry.

Goodman was born in poverty and spent his early years in an economically depressed Stockport in the 1920s. He was an only child but lived in an extended Jewish family; his two sets of grandparents were immigrants from Poland and Russia. His father was unemployed for long spells and in the 1930s moved to London in an unsuccessful bid for work. The politics of the family were on the Left and they took seriously the vision of a new Jerusalem.

During the war he served with the RAF and, waiting to be demobbed, wrote for The Soldier magazine. He soon got a job on the Manchester Guardian but left after some months, amid suspicions that AP Wadsworth, the editor, had fired him because of his membership of the Communist Party. He spent time on the Liverpool Daily Post, writing leaders, and then joined the News Chronicle in 1949. His reports on the dock strike that year established his reputation as a reporter on industrial relations.

Ten years later, when the Chronicle was taken over by Odhams, he went to the Daily Herald. In these years he became close to the leading figures in the trade union movement and in the Labour Party, particularly Aneurin Bevan and Michael Foot, his two heroes. At one time Foot’s wife approached him to write her husband’s biography.

He left the Herald (now The Sun) in 1969 to join the Daily Mirror. He also had attractive offers from the BBC to present his own news programme and to return to the Guardian with his own column. In 1970 he passed up the opportunity of winning a safe Labour seat in Leicester. Hugh Cudlipp, the Mirror editor, offered him his own column as an inducement to stay. By now he had established an unrivalled authority on the political and industrial issues of the day.

In these years Goodman was close to Harold Wilson and Jim Callaghan, both of whom he liked while appreciating their shortcomings. In 1974 he was a member of the Royal Commission on the Press (the third such body since 1945). In 1977 he and David Basnett, the trade union leader, wrote a minority report advocating the use of public funds to encourage diversity in the Press. Nothing was done about his recommendations and Goodman looked back on the episode as a waste of time.

In 1975 he took leave from the Daily Mirror to head the Government’s counter-inflation publicity unit. Conservatives objected to him holding the post as well as serving on the Royal Commission: its task was to sell the Government’s pay policy. However, the Treasury ignored it and Harold Wilson lacked the energy to get ministers to co-operate with it. Goodman returned to the Mirror a year later.

He was inseparable from the Daily Mirror and the Labour movement – at the time it was still the best-selling newspaper and a political force to be reckoned with. He was comfortable with its politics, which he helped to shape. Things went wrong at the end, however, when Robert Maxwell (whom he regarded as a monster) took control of the Mirror Group in 1984. He was a clumsy hands-on proprietor and unilaterally savaged a column of Goodman’s on the miners’ strike. A furious Goodman (who had just been elected journalist of the year) threatened resignation unless he was given an undertaking that it would not happen again.

He was fortunate enough to retire in 1986 with his pension still intact. Years later he confessed that he felt that he had been demeaned by working for Maxwell and that he should have resigned immediately. Professionally and politically the 1980s were a grim period; his kind of politics was on the back foot in the face of Margaret Thatcher and his paper was now challenged by The Sun.

Goodman’s judgement, as the doyen of industrial reporters, was widely respected. He knew who to talk to, considered the evidence and arrived at a clear and balanced view. He agreed with the thrust of Barbara Castle’s proposed reforms of the trade unions in 1969 but not how they were being implemented.

He was unenthusiastic about Blair’s new Labour project and considered the leader’s portrait of old Labour as a cruel caricature. He did not think that Blair’s team could hold a candle to the 1945 Attlee Government. Goodman also had a great capacity for friendship, usually but not exclusively on the Left. In the 1980s his main sources inside Thatcher’s cabinet were the “wets”, Peter Walker and Jim Prior.

He enjoyed a busy retirement, sustained by good health and a lively mind. He was short and stocky and his pleasant voice made him a natural broadcaster; his dignified bearing and fine mane of white hair made him stand out in any gathering. He was the founding editor, in 1989, of the British Journalism Review, and its success owed much to his dedication and editorial skills. At a dinner in 2002 to mark his retirement as editor Tony Blair paid tribute but then had to listen as Goodman’s reply included a withering verdict on the Labour government.

In 2003 Goodman wrote an autobiography, From Bevan to Blair, covering his 50 years in journalism. He had earlier written well-received books on Frank Cousins, the T&G leader, The Awkward Warrior (1979) and The Miners’ Strike (1985). The Cousins’ biography was written during a research fellowship at Nuffield College, Oxford, a project encouraged by his good friend Bill McCarthy, Professor of Industrial Relations at Oxford. He also wrote insightful and sympathetic obituaries for many newspapers, including the Independent, for the leading figures on both sides of industry, as well as Labour politicians.

He was sustained by a happy marriage to Margit Freudenbergova. A persecuted Jew, she had left on one of the last trains from Prague in 1939 and many of her family perished in the camps. He met her in Prague in 1945 and they married in 1947. He read widely, was a superb conversationalist and was a familiar figure at a corner table at lunch in The Gay Hussar in Soho. It was far cry from his deprived childhood in Stockport. As well as supporting Tottenham Hotspur, in Who’s Who he listed his recreations as pottery, poetry and “climbing – but not social.”

Geoffrey George Goodman, journalist and author: born Stockport 2 July 1921; Founding Editor, British Journalism Review 1989–2002, then Emeritus; CBE 1998; married 1947 Margit Freudenbergova (one son, one daughter); died September 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments