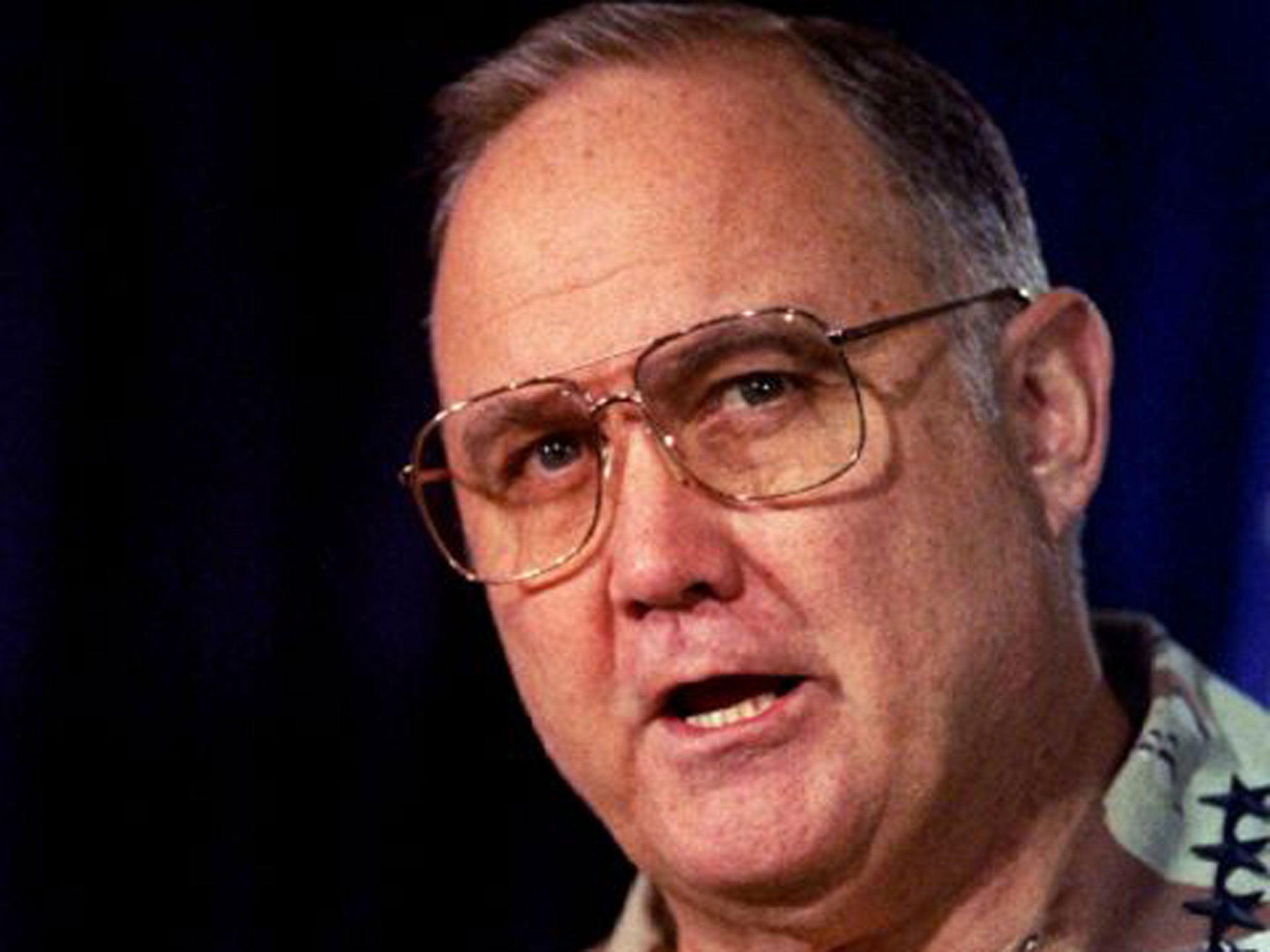

General Norman Schwarzkopf: Soldier who led the coalition force to victory in the first Gulf War

'The truth is, you always know the right thing to do,' he said. 'The hard part is doing it'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Not since the Second World War and its immediate aftermath, and Generals named Eisenhower, Patton and MacArthur, was there a US military hero like Norman Schwarzkopf. He had brains, self-confidence and swagger by the truckload. He gave quotes to die for. Most important of all, he was a winner.

The first Gulf war, in which Schwarzkopf commanded the 670,000-strong US-led coalition force that swept Saddam Hussein's army from Kuwait in 1991 in a ground war lasting 100 hours, restored to the American military the self-belief, reputation and prestige that had been lost in the disaster of Vietnam a generation earlier. And for the first time in almost half a century a general had caught America's national imagination.

There was never much doubt that Norman Schwarzkopf would be a soldier. His father was an officer in the US expeditionary force that had gone to Europe in the First World War, before a stint in civilian life as the first superintendent of the New Jersey State police (in which capacity he led the investigation into the kidnap and murder of the Lindbergh baby in 1932).

But by 1940 Schwarzkopf senior was back in the army, serving as a liaison officer in Iran and Europe. Later he would train Iranian security forces who backed the Shah during the 1953 coup. Thus the son who arrived at West Point in 1952 was already the quintessential army brat. Having lived half his life abroad, he spoke fluent French and German. In 1956 Norman junior graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering and was commissioned an infantry second lieutenant.

The most celebrated US military career in modern times began relatively quietly. Schwarzkopf had two domestic postings before a spell in Berlin, immediately before the erection of the Wall in 1961, after which he went back to West Point to teach engineering. Within a year, however, he had applied to go to Vietnam.

Between 1965 and 1971, Schwarzkopf served two tours in Vietnam. His heroism earned him three silver stars – the last of them when as battalion commander he went back into a minefield to rescue several badly wounded men – and forged a reputation that would never leave him, of a leader who was tough and demanding on the men under him but ready to risk his own life for theirs.

The nicknames they gave him, "Stormin' Norman" or "the Bear" reflected the grudging but genuine respect in which he was held (his wife would claim years later that of the two, he always preferred "Bear"). They might not appreciate his methods but, Schwarzkopf always insisted, it was for his mens' own good. "When you get on that plane to go home," he used to tell them, "if the last thing you think about me is 'I hate that son of a bitch,' then that's fine, because you're going home alive."

Vietnam also imparted a wider lesson (as it did to many US commanders who served there, among them Colin Powell) – that a successful war required a clear purpose, sufficient forces to do the job as quickly and efficiently as possible, and a defined exit strategy. In the first of America's two wars against Saddam, that doctrine was vindicated. In the second, waged by George W Bush, it was ignored, with disastrous results.

By the early 1970s Schwarzkopf was rising rapidly through the ranks. After a series of staff jobs, he was promoted to major general in 1982. A year later he found himself ground commander of American forces sent to the Caribbean island of Grenada by Ronald Reagan to reverse a left-wing coup. His role in what was codenamed "Operation Urgent Fury" was small, and outrage, both at home and abroad, was widespread at what seemed a blatant act of American imperialism. But this tiny war was a success, and the healing of the wounds of Vietnam had begun.

By 1988 Schwarzkopf had become a full four-star general, and was appointed to head US Central Command, with responsibility for the Middle East, south Asia and the Horn of Africa. Then, on 2 August 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait – and he found himself in charge of a very large war indeed. And though the ultimate military and diplomatic decisions were made by President George HW Bush, the Secretary of State James Baker, and Dick Cheney, then Defense Secretary, for the ordinary American public Gulf War One was Norman Schwarzkopf's war.

His press conferences, at which he appeared in battle fatigues with reporters as mere stage props, were tours de force. The war, an air bombardment and ground campaign, lasted six weeks in all, and the much vaunted Iraqi army collapsed like a house of cards. The hero of the hour was Schwarzkopf, and the general visibly revelled in his glory, proving himself a master of the soundbite in the process.

To hear him tell it, a key to victory was his "Hail Mary" move (the term refers to an ambitious play in American football), a bold advance across the western desert that outflanked the Iraqi forces and cut off their retreat when they were driven from Kuwait. Even more memorable was his reply when someone asked his opinion of Saddam's military prowess. "Hah," came the reply. "He is neither a strategist nor is he schooled in the operational arts, nor is he a tactician, nor is he a general. Other than that he's a great military man."

After the war, a video of highlights from his 27 news conferences became a commercial bestseller. Schwarzkopf returned home to 20th century America's version of a Roman triumph. There were parades in New York and Washington DC, and awards of every colour. The rights to his memoirs, It Doesn't Take a Hero, sold for $6m, a breathtaking sum at the time. Queen Elizabeth II made him an honorary knight, while the French foreign legion, some of whose men fought under him in Gulf War, bestowed on him the rank of private first class. Schwarzkopf remains the only American to be so honoured.

The war was not only the climax but also the last act of his military career. Having turned down the job of Army Chief of Staff, Schwarzkopf announced his retirement in summer 1991, ending an active service career of 35 years. In retirement he remained a celebrity, besieged by admirers whenever he passed through a commercial airport. In 1994 he had successful surgery for prostate cancer and quickly emerged as the country's best known campaigner for awareness of the disease.

In subsequent years his reputation waned somewhat. Some in the military accused him of turning his back on the army, seduced by fame and fortune in the civilian world. Others resented his less-than-gracious treatment of some fellow officers. More broadly, the first Gulf War came to appear less brilliant than it seemed at the time. A prostrate Saddam was allowed to stay in power, and to remain a thorn in America's side for a further dozen years. Should America – and therefore Schwarzkopf – have finished the job in 1991?

The question was implicitly answered in 2003. Schwarzkopf was on record opposing the invasion six months before it happened. His worries, over a lack of troops, inadequate post-war planning and a failure to understand the fraught history of Shias, Sunnis, and Kurds, were tragically borne out by events. As Schwarzkopf once remarked, about statecraft, military command and life in general, "The truth of the matter is that you always know the right thing to do. The hard part is doing it."

Herbert Norman Schwarzkopf, US general: born Trenton, New Jersey 22 August 1934; US Military Academy, West Point 1952-1956; commissioned US Army 1956; served in Vietnam 1965-1968, 1969-1971; major general 1982, lieutenant general 1986, general 1988; Commander-in-chief, US Central Command 1988-1992; Hon KCB 1991; married 1968 Brenda Holsinger (two daughters, one son); died Tampa, Florida 27 December 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments