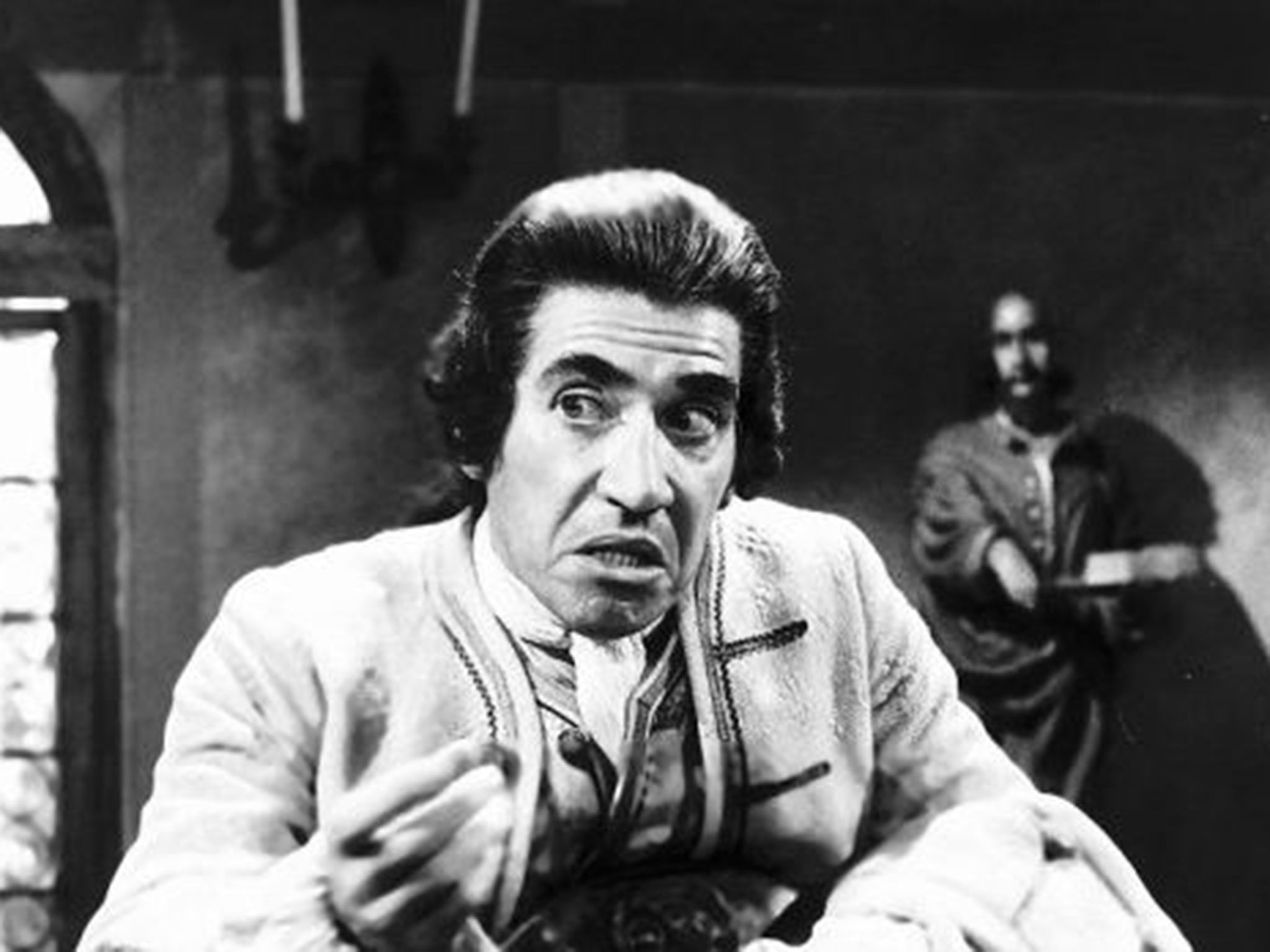

Frank Finlay: One of the finest character actors of his generation, who found fame as Casanova and in 'Bouquet of Barbed Wire'

He never courted fame, but simply worked hard, with wonderful results.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The fatherly Frank Finlay was a quietly masterful presence, and one of the finest character actors of his generation. A modest and generous performer, his skills seemed to conquer all genres and all mediums. But while his career was diverse (he appeared in plays by both Trevor Griffiths and Jeffrey Archer) his performances were consistently splendid.

He could suffer quite beautifully, for comic or tragic effect, whether he be Salieri, Casanova or the confused and obsessive paterfamilias of Bouquet of Barbed Wire, the 1976 television serial that made him a household name. He was a key player in the early days of both the English Stage Company at the Royal Court and the National Theatre, and while his film career had its moments (such as Polanski's The Pianist in 2002), the stage and television were much more bountiful places for his talents.

Physically, Finlay wasn't an obvious comic performer; his solemn, worried and conservative looks could have doomed him to a career of police inspectors. But in fact he could be hilarious: as the unsmiling Corporal Hill in Arnold Wesker's Chips With Everything (Royal Court, 1962) he was delicious when promising: “I will tear and mercilessly scratch the scorching daylights out of anyone who smarts the alec with me”, and made his announcement that “I never smile, I never joke” almost a lament.

By contrast, he was the essence of ineptitude as Dogberry in Franco Zeffirelli's carnivalesque Much Ado About Nothing at the Old Vic in 1965. (A BBC studio recording of the play capturing Finlay's performance in all its glory was believed lost, but was recovered in 2010.)

The son of a butcher, Frank Finlay was born in Farnworth, Lancashire in 1926. His Irish parents had come to England in the late 19th century as millworkers. He inherited a devout Catholicism from them, and after schooling at St Gregory the Great and Bolton Technical College, at 14 he began work as a butcher's apprentice, but after dabbling in acting at Farnworth Little Theatre, in 1951 he joined a fortnightly rep in Troon, Ayrshire.

His professional debut came the following year at Halifax; he then spent 10 months at Sunderland with The Mayville Players, performing works by RF Delderfield and future Dad's Army player Arnold Ridley. He won the Sir James Knott Scholarship to Rada, and from there worked at Bolton Rep and Guildford before ageing up to originate the role of the tragic idealist Harry Khan, rendered impotent and ultimately incontinent by the failure of a socialist ideal, in Arnold Wesker's Chicken Soup with Barley at the Belgrade, Coventry in 1958.

The Royal Court had initially been unconvinced by the play and had decided to test it out in the provinces; its success led to The Wesker Trilogy (1959), a major event of the revolution that was taking place in Sloane Square. (The posters on the fronts of London buses read “You Must See The Wesker Trilogy”.) The trilogy decisively announced Finlay in the theatre.

He continued at the Royal Court with Sergeant Musgrave's Dance (1959) by John Arden, and the more gently progressive Sugar In The Morning (1959) by Donald Howarth. Olivier then invited him to join the new National Theatre, originally based at Chichester. He played the Gravedigger in the NT's opening production of Hamlet in 1963, and stayed for four years; his most celebrated moment was undoubtedly as Iago to Olivier's Othello in 1964.

In The Sunday Times, Harold Hobson called the performance: “convincing and powerful… less a Machiavelli than one of those amoeba-minded Southern senators who still foam at the mouth at the thought of a black man and a white woman getting into bed together.” The film of the production two years later saw Finlay one of four cast members nominated for an Oscar.

The new writing of the 1970s provided him with some fine opportunities: as the boozy trade unionist Sloman in Trevor Griffiths' The Party (in which Olivier bowed out as an unlikely Glaswegian communist), and as Czech communist Josef Frank in Howard Brenton's Weapons of Happiness, the first play commissioned by the new National Theatre on the South Bank.

A brief stint with the RSC in the late '60s saw him star in a work by one of the hottest writers of the era, David Mercer, as the Marxist critic of After Haggerty (Aldwych, 1970), then with another, Dennis Potter, as Christ in Son of Man (Roundhouse, 1969). He worked with Potter again on television in the inevitably controversial Casanova (1971), a superbly melancholic serial that earned him a Bafta nomination; having triumphed the previous year in a magnificent BBC Play for Today written by Ingmar Bergman entitled “The Lie”, which microscopically examined the collapse of a middle-class marriage, Finlay was now established as a television face, and also a favourite for dramas of tortured sexual entanglement.

He was therefore the perfect choice for Bouquet of Barbed Wire (1976), which had 26m people transfixed by its story of a father's blindly obsessive love for his manipulative daughter (Susan Penhaligon). Also noteworthy among his many television roles were a charming BBC telling of 84, Charing Cross Road (1975), playing Hitler in The Death of Adolf Hitler (1972) and giving a lovely turn as the father of Helen Mirren's Jane Tennison in the final Prime Suspect (2006).

Frank Finlay called acting “his hobby” and this perhaps gives some clue as to why he never quite won the same recognition of many of his contemporaries. He never courted fame, but simply worked hard, with wonderful results.

Francis Finlay, actor: born Farnworth, Lancashire 6 August 1926; married 1954 Doreen Shepherd (died 2005; one daughter, two sons); died Shepperton, Middlesex 30 January 2016.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments