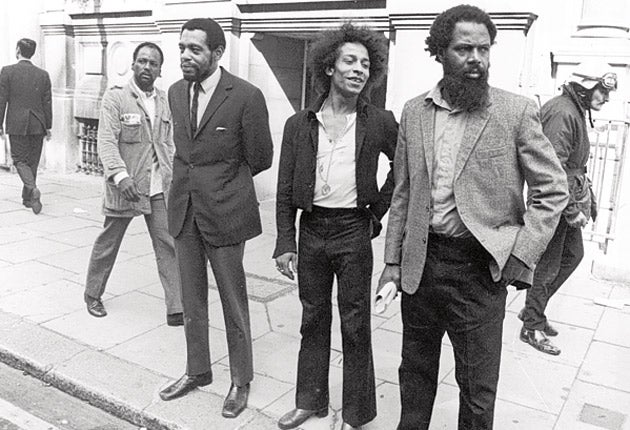

Frank Critchlow: Community leader who made the Mangrove Restaurant the beating heart of Notting Hill

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For many years Frank Critchlow played a central role in the Notting Hill's black community. He set up the Mangrove Restaurant, the first black restaurant in "the Grove". This apparently innocuous activity set him on a collision course with the local police, who equated black radicalism with criminality. Police persecution of the Mangrove became emblematic of the experience of the black community at large, and Critchlow's struggle brought the British Black Power movement its first major victory.

Critchlow was born in Trinidad in 1931. He moved to Britain at the age of 21 and worked for a time maintaining gas lamps for British Rail. In 1955 he took a new course, becoming band leader with The Starlight Four. In the late 1950s Critchlow changed direction again, setting up the El Rio, a small coffee bar in Westbourne Park Road, Notting Dale, and then in 1968 the Mangrove Restaurant in All Saints Road.

The Mangrove, which served the cuisine Critchlow had learned from his mother, soon became the beating heart of Notting Hill's West Indian community. Black people who wanted advice on housing or legal aid went there, as did black radicals who wanted to discuss the revolution in the Caribbean, or the fortunes of the American Black Power movement, as well as bohemian "whitebeats" looking for an alternative to square English culture. The community aspect of the Mangrove was evident in the pages of The Hustler, a small community newspaper edited by Courtney Tulloch which was produced on the premises.

The Mangrove, like the Rio before it, gained a reputation for radical chic. The Rio came to public attention in 1963 when it was referred to in the Denning Report on the Profumo Affair as one of Christine Keeler's and Stephen Ward's regular haunts. The Mangrove also saw its fair share of big names including the black intellectuals CLR James and Lionel Morrison, celebrities such as Nina Simone, Sammy Davis Jr, Jimi Hendrix and Vanessa Redgrave, and white radicals like Colin MacInnes, Richard Neville and Lord Tony Gifford.

But the thriving restaurant soon came under attack. "The heavy mob", a group of officers who according to The Hustler policed Notting Hill like a colonial army, raided the Mangrove 12 times between January 1969 and July 1970. They claimed that the Mangrove was a drugs den, in spite of the fact that their repeated raids never yielded a shred of evidence. The police pursued Critchlow on a host of petty licensing charges, including permitting dancing and allowing his friends to eat sweetcorn and drink tea after 11pm. Critchlow stood resolutely against this persecution. "Unless you're an Uncle Tom," he protested in an interview with The Guardian in 1970, "you've got no chance."

Darcus Howe, who was working at the Mangrove, urged Critchlow to look to the community for support. Together, Howe, Critchlow and the local Panthers organised a March. On 9 August 1970, 150 protesters took the streets, flanked by more than 700 police. Police intervention resulted in violence and Critchlow, Howe and seven others were charged with inciting riot.

The march sent shockwaves through the British polity. Special Branch was called in, and files at the National Archives show that the Home Office considered trying to deport Critchlow. Meanwhile, the Mangrove Nine made legal history in demanding an all-black jury, taking control of the case and emphasising the political nature of police harassment. Police witnesses described Critchlow's restaurant in lurid terms, as a hive of "criminals, ponces and prostitutes". Critchlow fought back with numerous character witnesses who defended his reputation as a respected community leader.

After 55 days at the Old Bailey Critchlow and his fellow defendants were acquitted. What is more, 28 years before the Macpherson Report, the judge publicly acknowledged that there was "evidence of racial hatred" within the Met. Horrified, the Assistant Commissioner wrote to the Director of Public Prosecutions seeking a retraction of the judge's statement. The Home Secretary, Reginald Maudling, arranged a meeting between the judge and senior civil servants but the statement was never withdrawn.

The case did not end institutional racism, but, as Critchlow put it, "It was a turning point for black people. It put on trial the attitudes of the police, the Home Office, of everyone towards the black community. We took a stand and I am proud of what we achieved – we forced them to sit down and rethink harassment."

In the '70s Critchlow founded the Mangrove Community Association, which continued the work begun by the restaurant, organising demonstrations against apartheid in South Africa, institutional racism, and supporting national liberation movements from Africa to the Middle East. Critchlow was also instrumental in establishing and running the Notting Hill Carnival. According to Tulloch, while the Carnival came from the community rather than any individual, there was a group of Trinidadians with "a tremendous wealth of serious musical ability", including Critchlow, who set the ball rolling. He continued to be involved as it grew in scale, defending it for many years from "McDonaldisation".

Police persecution of the Mangrove never wholly ceased. In 1989 Critchlow was in court once again, this time accused of drug-dealing, and again, church leaders, magistrates, community leaders black and white, all spoke out in his defence. Again he was acquitted of all charges. The final victory was Critchlow's; in 1992 he sued the Met for false imprisonment, battery and malicious prosecution. The police refused to admit fabricating evidence but paid him a record £50,000. Speaking at the time, he said that the money would help "in a small way. But it is no compensation for what they did. Everybody knows that I do not have anything to do with drugs. I don't even smoke cigarettes. I cannot explain the disgust, the ugliness, not just for me but for all my family, that this whole incident has caused."

Looking back, Lord Gifford commented, "Frank was determined to build a business in and for the North Kensington Community. He persevered in the face of adversity and harassment. His restaurant was a place where all people of good will were welcome. He was a hard-working pioneer who was not recognised as he should have been." For his friend Darcus Howe, Frank Critchlow was simply, "a Caribbean man who did ordinary things in extraordinary ways."

Robin Bunce and Paul Field

Frank Critchlow, community activist: born Trinidad 13 July 1931; three daughters, one son; died 15 September 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments