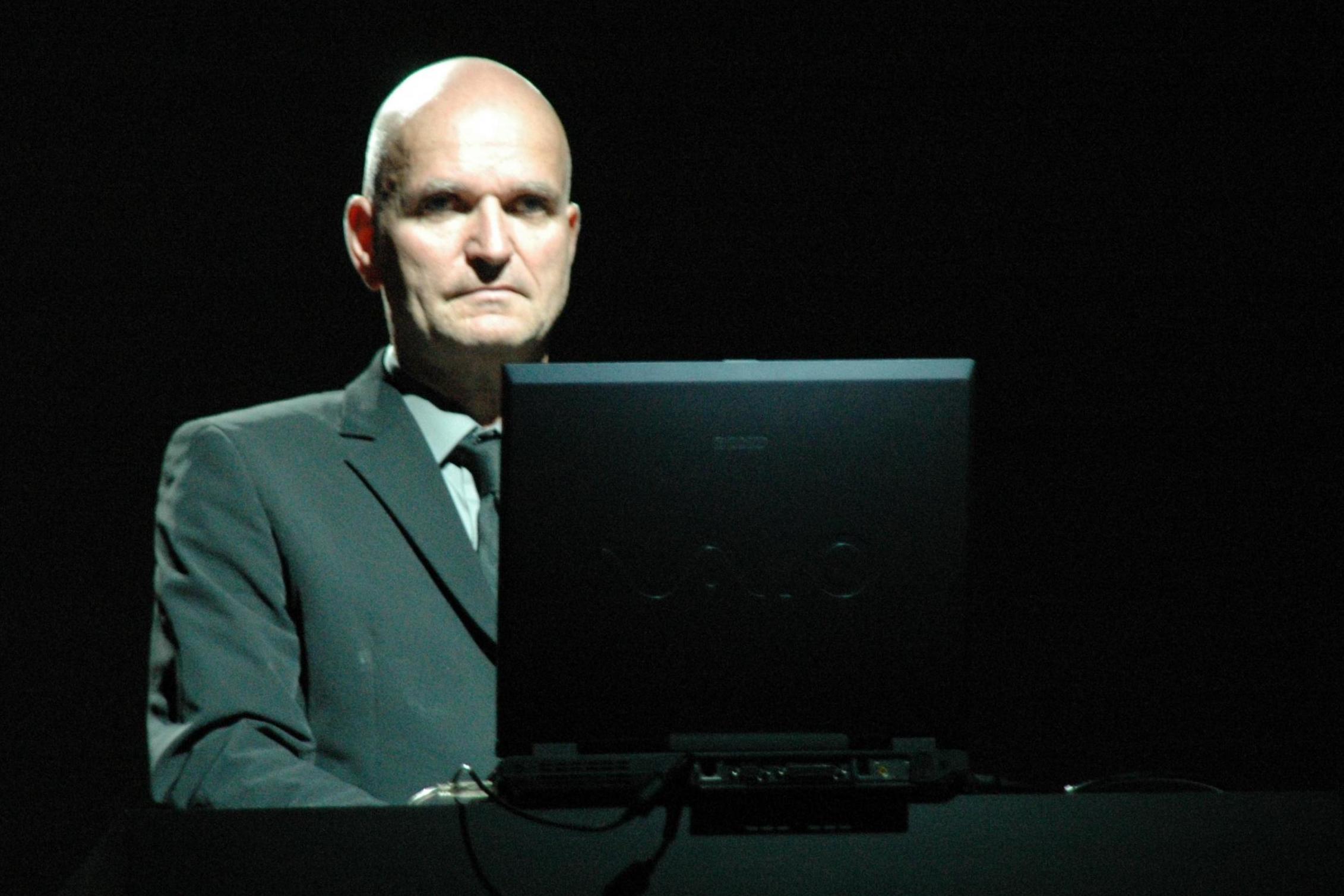

Florian Schneider: Kraftwerk co-founder whose electronic innovations changed the course of pop music

His group pioneered a new approach to composition, one that would be hugely influential in the 1970s and 1980s

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Florian Schneider, who has died of cancer aged 73, was the co-founder of Kraftwerk, the German group whose embrace of synthesisers and new digital technology in the 1970s changed the pop-punk music scene.

Schneider’s parents were Evamaria and Paul Schneider-Esleben, the latter of which was a renowned architect who designed Cologne Bonn airport. Schneider grew up in a wealthy, artistic household.

While studying flute at the Dusseldorf Conservatory in 1968 he befriended fellow student Ralf Hutter. Both youths were involved in the local rock scene that emphasised experimentation and looked to Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Electronic Music Studios in Cologne for inspiration. The duo joined Organisation, a band who fitted the then-popular progressive rock mode of musicians jamming over simple rhythms.

Organisation released one album, Tone Float, in 1969 before the two friends formed Kraftwerk (German for “power station”). In 1970 Schneider became interested in making music using synthesisers – his family wealth allowed him to purchase what were extremely expensive instruments back then – and, that same year, he visited an exhibition of the British artists Gilbert and George, noting their identikit suits and haircuts.

Hutter and Schneider signed as Kraftwerk to Philips in 1970 and released three albums – Kraftwerk (1970), Kraftwerk 2 (1972) and Ralf und Florian (1973) – that employed traditional instrumentation, which the duo then distorted using various electronic effects.

With Autobahn (1974), Kraftwerk offered up an entirely electronic approach to making contemporary music. While a select few rock groups in the US and Europe had experimented with synthesisers and drum machines, Kraftwerk took it to a new level: sonically Autobahn could still be classified as prog-rock yet Kraftwerk’s man-machine aesthetic set them apart from their contemporaries.

An edited 45” of the title track became a surprise hit single in both the UK and US and suggested pop possibilities few had recognised. Kraftwerk toured the US and UK for the first time, increasingly reliant on keyboard synthesisers – Schneider now stopped playing flute – and began processing their vocals through vocoders. This breakthrough didn’t immediately win Kraftwerk a large international audience – Radioactivity (1975) received poor reviews and sales and the British music media and Musicians Union both dismissed the band as “robots, not real musicians” alongside employing negative stereotypes of Germans.

Trans-Europe Express (1977) won a far warmer welcome alongside an endorsement from David Bowie while post-punk UK synthesiser-led bands The Human League, Ultravox, Depeche Mode and Soft Cell were all disciples.

The Man-Machine (1978) took Kraftwerk’s machine-as-master concept a stage further, although Computer World (1981) found Kraftwerk bereft of new ideas and memorable songs. As if to demonstrate the point, an older song, “The Model”, from The Man-Machine, topped the UK charts in February 1982.

Just as Kraftwerk became a spent creative force, their influence was everywhere: in the US pioneering rap and techno DJs began mixing Kraftwerk in their sets. By now Kraftwerk’s live show incorporated robots and the four identically dressed and coiffured band members effectively removed themselves from stage across the performance.

Schneider and Hutter became studio obsessives, spending years in their recording studio yet releasing only one one further single and album across the 1980s – both disappointing – while 1991’s The Mix album found the duo remixing their earlier recordings (and achieving little by doing so).

Kraftwerk’s last studio album, Tour de France Soundtracks (2003), relied on a reworking of their 1983 “Tour de France”. The group became regulars on the international tour circuit, where young audiences embraced the band as pioneers of electronic dance music, and their spectacular performances proved suitable for everywhere from the Tate Modern to the Tribal Gathering festival.

Hutter and Schneider almost never gave interviews and ran Kraftwerk with monastic discipline (suing a former member who published a memoir on his time in the group). When a press release announced that Schneider had left Kraftwerk in November 2008, few were wiser as to why.

Schneider’s intense privacy was maintained after leaving Kraftwerk and little is known as to what he got up to – more than once there was speculation he had died.

Unexpectedly, in 2015, he released “Stop Plastic Pollution”, an electronic protest song recorded with Dan Lacksman and Uwe Schmidt, and spoke at an environmental gathering about his concern for the world’s oceans.

He died of cancer in April and his family held off announcing this until after his funeral. He is believed to be survived by a daughter.

Florian Schneider, musician, born 7 April 1947, death announced 6 May 2020

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments