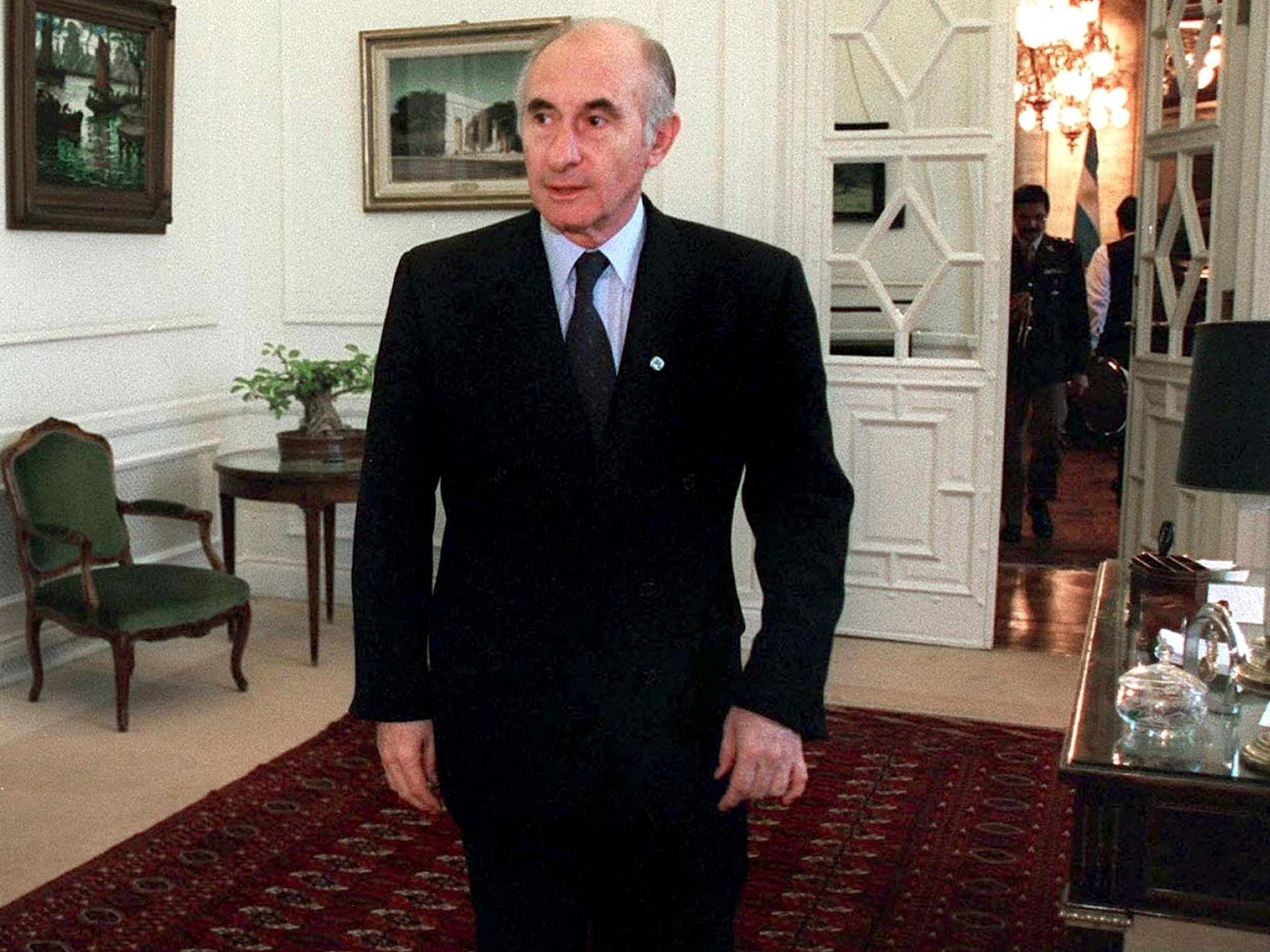

Fernando de la Rua: Argentinian president who fled office besieged by riots

De la Rua was elected as a change-maker but led his country for little more than a year

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Fernando de la Rua’s dramatic departure by helicopter from the roof of the Argentinian presidential palace in 2001 epitomised the tumult of his short-lived administration, a period of financial free-fall and deadly social unrest in one of Latin America’s largest economies.

De la Rua, who has died aged 81, was a man with an aggressively bland public personality – he proudly called himself “boring” in a TV campaign advertisement – was greeted as a welcome change to Argentinian politics when he came to power in December 1999.

A legal scholar and longtime senator who served briefly as the first elected mayor of Buenos Aires, he emerged as a consensus choice for president in a centre-left alliance that was seeking to quell the chaos fomented by a decade of increasingly erratic rule under Carlos Menem.

De la Rua inherited the pandemonium, presiding over a crisis that thrust millions of middle-class Argentinians into poverty, sent unemployment soaring above 20 per cent and set the stage for default on the country’s $132bn (£100m) debt.

A century earlier, Argentina had been one of the 10 richest nations in the world. But the country had long teetered over the economic and political abyss under flamboyant nationalist-populists such as Juan Peron from 1946 to 1955 and the military leaders who led the 1976-83 junta during which tens of thousands of citizens were killed or disappeared.

Menem, elected in 1989, had also struggled to combat unemployment and hyperinflation, and his conservative policies enraged many fellow Peronists – followers of the Justicialist Party of the late strongman who traditionally favoured labour and big government. He privatised state-owned companies, curbed the power of unions, scissored state subsidies and pink-slipped thousands on the bloated government payroll.

In his most controversial manoeuvre, Menem fixed the exchange rate of the Argentinian peso to the American dollar one to one. It brought a windfall of foreign investment at first but ultimately proved destabilising, making the country impossibly expensive for the vast majority of Argentinians.

Menem did himself no favours with an authoritarian tendency that led him to alter the constitution to permit him to seek a second consecutive term. As his country slid into recession, he did little to hide his taste for Ferraris and penchant for squiring beauty queens. His political actions and personal extravagance opened the way for De la Rua, a stalwart of the centrist Radical Civic Union that forged an alliance with disgruntled Justicialists.

De la Rua, who played up his sedate image in an election that was essentially a referendum on Menem, did not rouse Argentinians with his vibrant oratory or record, but he trounced Justicialist candidate Eduardo Duhalde.

Congress, along with many governorships, remained in Peronist hands. And De la Rua’s Alianza coalition was fragile – less ideologically than opportunistically aligned. The country was sliding deeper into recession, and De la Rua, by most accounts, hesitated to take assertive steps to reverse course. He said drastic moves would spook investors or else provoke economic catastrophe that the political opposition could then use as ammunition against him.

Under pressure from the International Monetary Fund, he made gestures towards austerity, including an unsuccessful effort to sell the luxurious presidential jet Tango 01 that Menem purchased for $66m. But he largely maintained Menem’s economic policies. Meanwhile, it became cheaper for investors to park money in Brazil and other countries that had devalued their currency.

De la Rua’s coalition frayed with an alleged vote-buying scandal in late 2000 in which several administration officials were accused of paying senators $5m to pass a bill weakening workplace protections. His vice president resigned, reportedly in protest of De la Rua’s unwillingness to investigate the charges vigorously. The president’s approval rating plummeted to 7 per cent, and the alliance was walloped in the 2001 midterms.

After a bank run in November 2001, the economy minister Domingo Cavallo imposed the “corralito”, a last-ditch move severely limiting bank withdrawals. Across the country, protesters wielding pots and pans clanged out their anger. Some started fires on the boulevards of the capital city. De la Rua declared a state of emergency, which did little to lessen public rage. Demonstrators turned more violent and there was looting.

Authorities deployed tear gas and rubber bullets and rode through the streets on horseback, striking protesters with clubs. Marchers yelled back: “Assassins! Assassins!” More than 20 people were killed in confrontations with police, and dozens more on both sides were injured.

De la Rua’s attempts to form a new government with the opposition were rebuffed. In a position he described as “total solitude”, he tendered his resignation on 20 December and alighted by helicopter. It was widely seen as a moment of disgrace.

In a 2016 interview, he blamed the IMF and his political opposition for creating conditions ripe for a “civil coup”, accusing Peronists and the media of encouraging the protests and then blaming the government for repression. He also criticised the head of presidential security for insisting on his evacuation by helicopter. “That was a mistake,” he said, “like all those cases in which one allows an image to become a symbol.”

During a series of caretaker administrations and after the election of Peronist Nestor Kirchner in 2003, the government abandoned the fixed exchange-rate system and broke with the IMF by defaulting temporarily on its debt. The economy fell sharply in early 2002 but began to skyrocket after that. A demand for Argentinian commodities such as beef and soybeans helped to generate ample financial reserves.

Fernando de la Rua was born in Cordoba, Argentina’s second-largest city in 1937. He received a doctorate in law from the University of Cordoba at 21 and began his rise in the Radical Civic Union while writing books on legal procedure.

In 1973, he was elected as a senator representing Buenos Aires and also was the vice presidential running mate of Ricardo Balbin, who lost decisively to Peronist candidate Hector Campora. De la Rua returned to legal practice during the junta years and resumed his senate career after the military rule.

In 1996, he became Buenos Aires’s first elected mayor, a position previously filled by presidential appointment. His term at the helm of Argentina’s largest city, with 12 million inhabitants, was perhaps the high point of his career. He vowed to emphasise probity, fiscal restraint and good services in a municipality not known for any of those qualities.

He was credited with transforming a $600m deficit into a surplus by targeting sticky-fingered city officials and politically connected business executives who had wangled sweetheart deals. He also grew the city’s subway system. His reputation as a municipal leader helped elevate him to the presidency.

De la Rua faced trial in 2012 and 2013 for his alleged role in the vote-buying scandal that tarnished his administration. He and several colleagues were acquitted. “With this verdict,” he said, “I have recovered my dignity.”

He is survived by his wife, Ines Pertine Urien, whom he married in 1970, and three children.

Fernando de la Rua, born 15 September 1937, died 9 July 2019

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments