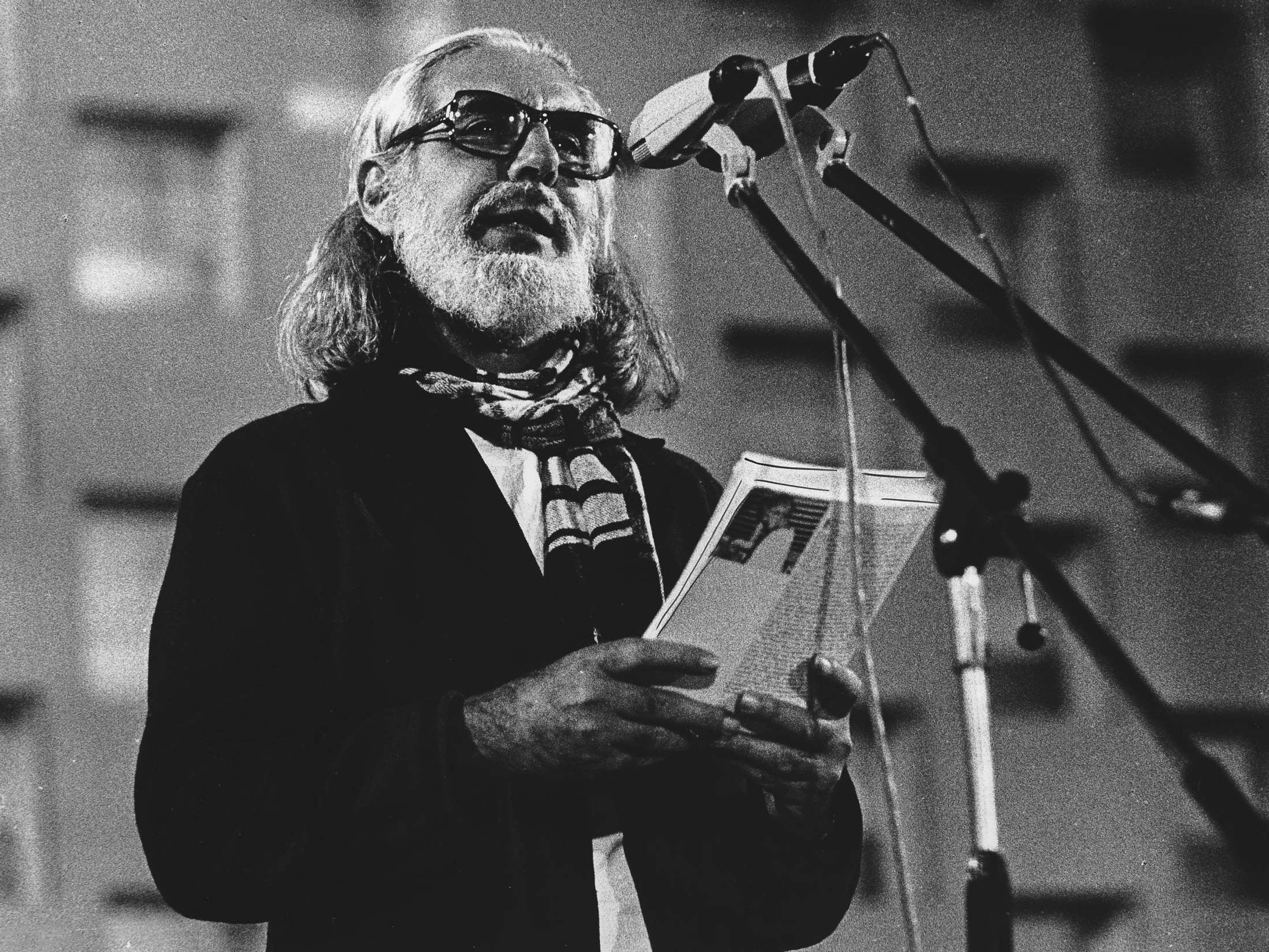

Ernesto Cardenal: Nicaraguan poet and priest who railed against autocracy

He was revered as a literary and moral beacon in the Latin American nation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Father Ernesto Cardenal was a Nicaraguan poet, priest and political revolutionary who wielded his pen as a weapon against two autocratic regimes: the Somoza family dynasty and the left-wing Sandinista party that took its place.

For many Nicaraguans, Cardenal, who has died aged 95, was revered as a literary beacon and a moral authority, a Catholic priest who drew on Marx as well as the Gospels to champion social justice in his ministry and writings.

One of Latin America’s most acclaimed poets, he wrote verses that offered a cosmic fusion of spirituality, politics, science and history, while appearing at frequent lectures and readings that made him a kind of international ambassador for Nicaragua.

Cardenal drew few boundaries between his callings. The son of a wealthy Nicaraguan family, he fought with a revolutionary group in his late twenties, then emerged as a leading proponent of liberation theology, which emphasises Jesus’s message to the poor and oppressed.

With a thick beard and signature black beret, he celebrated mass with Sandinista revolutionaries in the jungle, later joining their leader Daniel Ortega when those forces marched into Managua in 1979 and toppled the Somoza family, whose rule had lasted more than 40 years.

Declaring that “the triumph of the revolution is the triumph of poetry”, he went on to work for nearly a decade as Nicaragua’s minister of culture, angering the Vatican with his mix of politics and religion while aiming to teach tens of thousands of Nicaraguans how to read and write.

Cardenal traced his religious convictions to the years he spent at a Trappist monastery in Kentucky, where he befriended Thomas Merton, a distinguished writer and priest. He later completed his religious training in Mexico, Colombia and Nicaragua, where he was ordained in 1965 and settled on the Solentiname Islands in Lake Nicaragua.

He had originally intended to establish a parish church. Cardenal, a sculptor as well as a writer, instead presided over a sprawling art colony, turning Solentiname into a haven for painters and spiritual seekers alike. On Sundays, he led the islanders in discussions of Christianity, eventually recording their conversations and adapting the dialogues into a multi-volume work, The Gospel in Solentiname (1975), considered a touchstone of liberation theology.

Some of the islanders joined the Sandinistas, organising in a 1977 raid against Anastasio Somoza Debayle’s forces with the blessing of Cardenal. The government responded by destroying the Solentiname chapel and other buildings, and Cardenal was labelled the “number one enemy of the people”.

He later served in the Sandinista cabinet alongside his brother, education minister and fellow Catholic priest Fernando Cardenal, who died in 2016. Both men defied Pope John Paul II’s order to quit their government jobs and focus on their ministries, and during a 1983 visit to Managua the pope publicly reprimanded Cardenal, reportedly telling him to “straighten out your position with the church”.

The next year, Cardenal was suspended from the priesthood, setting off a break with the church that was repaired only last year, when he was absolved by Pope Francis. By then, Cardenal had become an outspoken critic of Ortega, whose party had stifled a rebellion from a CIA-backed army known as the Contras and was accused of rampant corruption and human rights abuses.

Ernesto Cardenal Martinez was born in Granada, on the shores of Lake Nicaragua, in 1925. After graduating from a Jesuit high school, he studied literature at the National Autonomous University of Mexico and at Columbia University in Manhattan, where he immersed himself in American poetry. He saw the form as a way for Latin American nations to assert independent political identities: poems such as “Zero Hour” and “With Walker in Nicaragua” recalled the history of US imperialism through figures such as Sam Zemurray, the head of United Fruit Company, and William Walker, who conquered Nicaragua in the mid-1850s.

Cardenal also spoke out against the Somoza regime in his verse, skirting government censorship by publishing outside the country as an “anonymous Nicaraguan”. His later works increasingly incorporated scientific themes, notably in Cosmic Canticle (1989), a 500-page poem that drew on the theories of physicists such as Richard Feynman and Stephen Hawking.

In recent years he led a Granada cultural centre, the Casa de los Tres Mundos, and received literary honours including Chile’s Pablo Neruda Ibero-American Poetry Award and Spain’s Reina Sofia poetry prize.

Ernesto Cardenal, poet, priest and revolutionary, born 20 January 1925, died 1 March 2020

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments