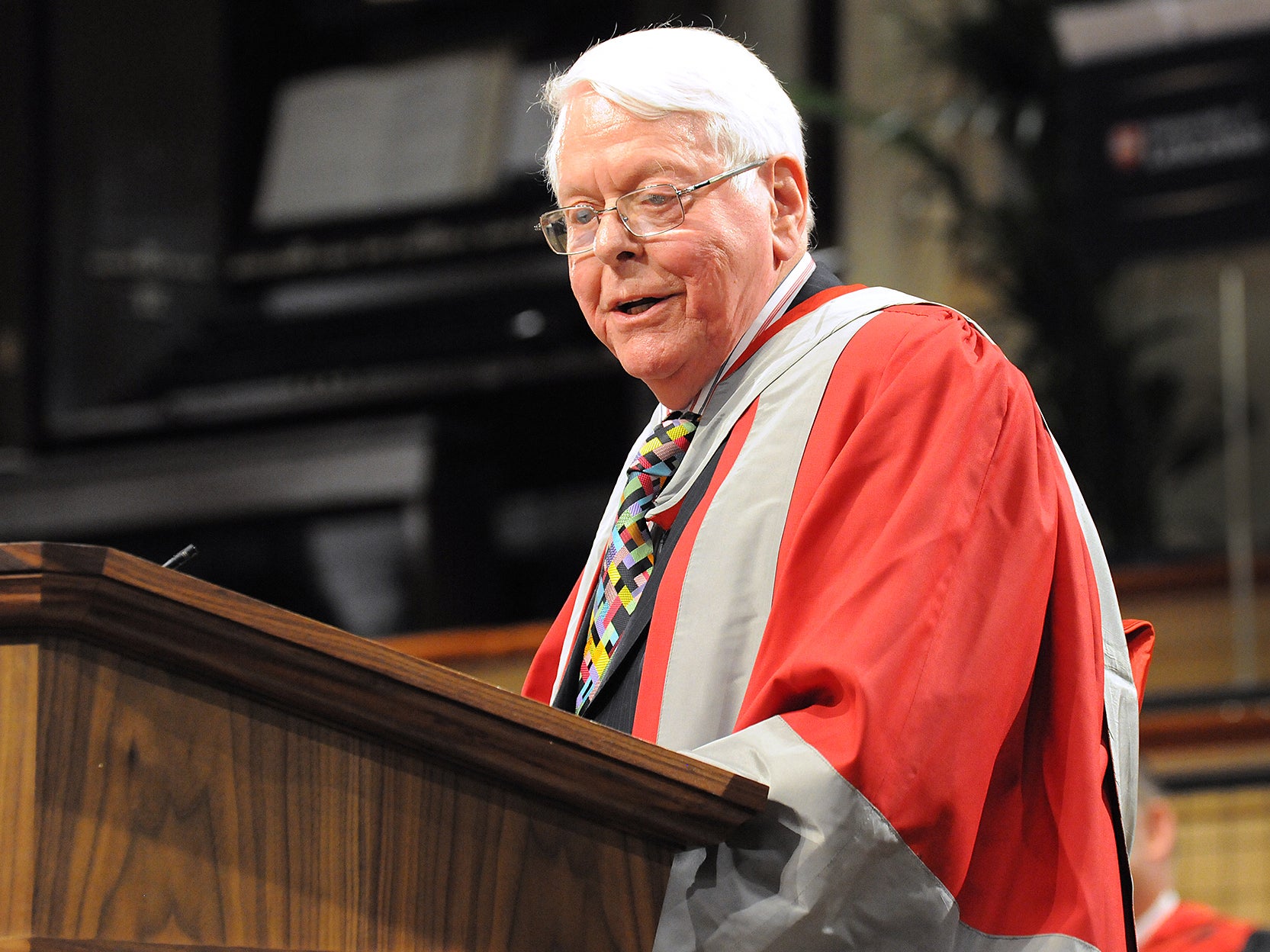

Eric Dunning: Scholar who got the ball rolling for sports sociology

At a time when football was not a respectable research field, the sociologist got stuck in – and made sure it became one

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Professor Eric Dunning was a pioneer and founding father in the sociology of sport. From the 1980s to 2000s, whenever “football hooliganism” was in the news, Dunning was the familiar expert on television and radio.

He was born in Hayes, Middlesex, the second son of Sidney Dunning and Florence Daisy Morton.

After attending Acton County grammar school, in 1956 he entered what was then University College Leicester, where he attended Norbert Elias’s introductory lectures in sociology. He was so entranced that he switched from his intended subject of economics to become a sociologist.

While at Acton, he had learned German, which proved to be of great significance as he was able to read Elias’s magnum opus, Uber den Prozess der Zivilisation it’s original form from 1939.

At the time, Elias was little known and the book only appeared in English, as The Civilising Process, many years later. Dunning always considered himself a sociologist tout court, not just of sport, and throughout his career took part in the theoretical debates that raged among his peers, acting as a prominent champion of Elias’s developmental or “process” perspective.

Seeking an area for postgraduate research, Dunning asked Elias whether football was a respectable field for research. At that time it was not: among British sociologists there was often, as Dunning recalled, “a contemptuous dismissal of sport as an area of sociological enquiry”. Dunning and Elias set out to change that, and in effect founded the sociology of sport, which today is a thriving field.

Dunning’s postgraduate work focused on the development of football from a rough and wild folk game into a modern sport, characterised by formal organisation with elaborate written rules, one object of which was to regulate, and steadily reduce, the socially permitted level of violence within the game – a manifestation of a civilising process.

The two papers which Dunning published on football, in History Today in 1963 and New Society in 1964 were among the earliest, and in Britain were probably the very first, published pieces of research to examine sport from a sociological perspective.

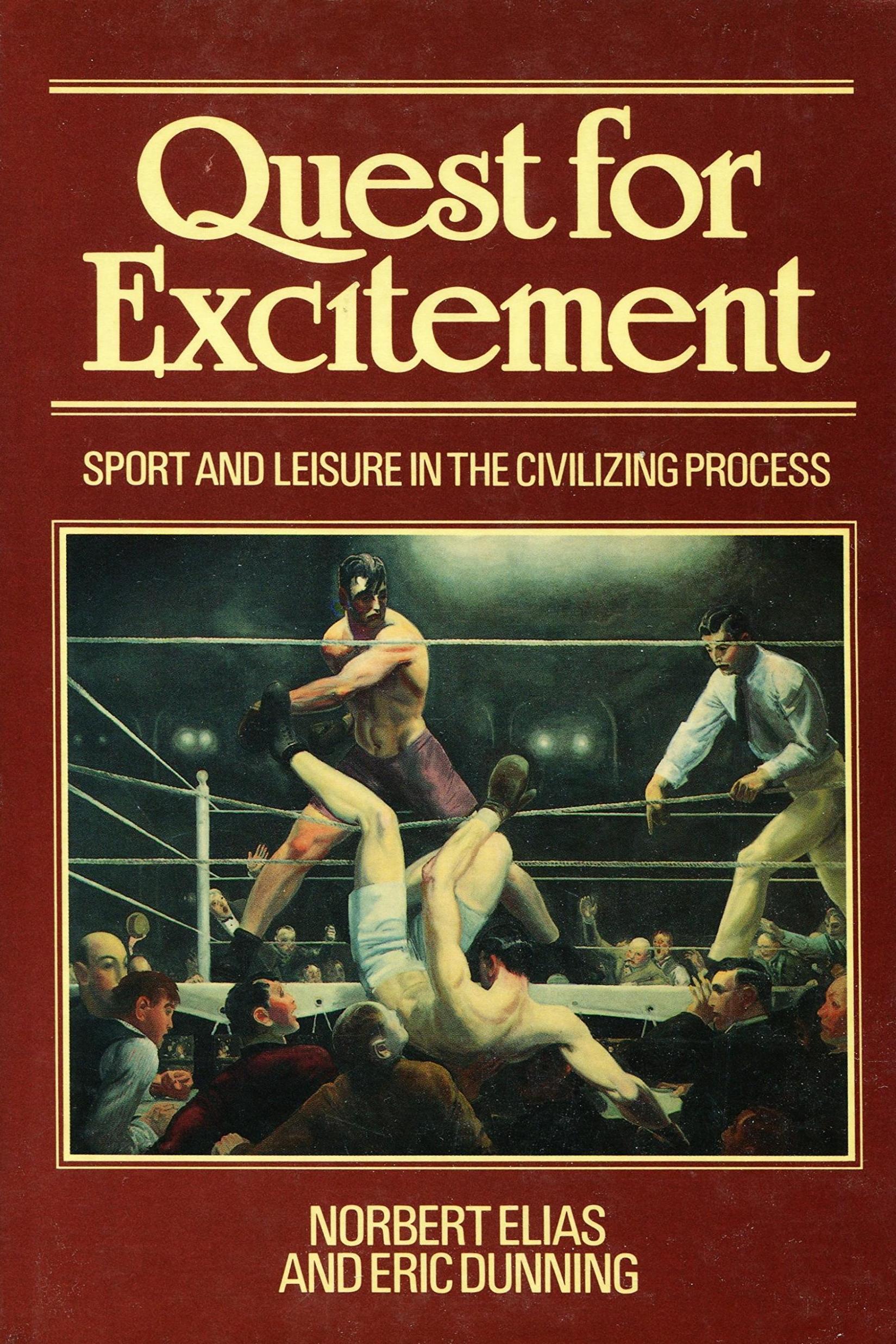

Dunning authored or edited 14 books and wrote almost a hundred scholarly papers on sport. Quest for Excitement (1986, republished 2008), co-authored with Elias, has been highly influential in generating a more theoretically informed sociology of sport and has been translated into six languages. Their essays, separately and together, covered the development of sports and leisure from the ancient Greek Olympics to the present day.

Among many other things, they stressed how sports gradually developed rules to maintain the “tension balance” or level of excitement for both players and spectators; the offside rule in football or the LBW rule in cricket are examples of this. The theme is developed in Barbarians, Gentlemen and Players (1979), his study with Ken Sheard of the development of rugby, which is arguably the best sociological study of the development of any sport.

From 1984 onwards, Dunning and his Leicester colleagues produced several books on spectator violence, and the work of what became known as the “Leicester School” is regarded as the most substantial and influential work in this area, the starting point for all subsequent research.

They observed football hooliganism at first hand, and served as advisers to (among others) Lord Justice Taylor in his report following the Hillsborough disaster of 1989. But their historical perspective served as an antidote to some of the more hysterical commentary of the time on the problem of disorderly spectators.

They were able to show that it was not a new problem; it could be traced back many decades. Nor was it associated exclusively with football, and it was not uniquely a British problem either. What was probably true, though, was that violent incidents had over time become more associated with sporting events and less with industrial, political or civil conflict in general.

Eric Dunning’s outstanding contribution to the sociology of sport was recognised when his book Sport Matters was awarded the North American Society for the Sociology of Sport prize as the best book published in the field in 1999.

In 2008 he was presented with a Festschrift and in 2013 the University of Leicester, where he spent his entire academic career, conferred upon him the degree of Doctor of Letters honoris causa.

Dunning was an inspirational lecturer and a natural teacher who conveyed complex ideas with great clarity. To colleagues and students he always charitable with his time, help and advice. To his friends he will be remembered as a bon viveur who loved wine and jazz, a teller of jokes and stories but, above all, as an extraordinarily kind and generous person.

He is survived by his two children Michael and Rachel, grandchildren Florence and Isabelle, and his brother Roy.

Eric Dunning, sociologist, born 27 December 1936, died 10 February 2019

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments