Elizabeth Wurtzel: Prozac Nation author whose candid prose triggered a memoir boom

She wrote provocatively about personal and mental health struggles, attracting both admiration and scorn

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Elizabeth Wurtzel chronicled her struggles with depression and drug addiction in bestselling memoirs that helped to spur a boom in confessional writing, turning her into a Generation X touchstone at 27 with the publication of Prozac Nation.

Wurtzel, who has died aged 52, announced in 2015 that she had breast cancer, a challenge that she dismissed as “nothing” compared with stemming her drug use or overcoming the death of her rescue dog Augusta.

Writing with extreme candour, Wurtzel was one of several authors who helped to reinvigorate the personal memoir in the 1990s. The form had long been dominated by politicians, artists or entertainers. Wurtzel was instead a self-described “twenty-nothing”, largely unknown outside circles who read her rock criticism in publications such as The New Yorker and New York magazine.

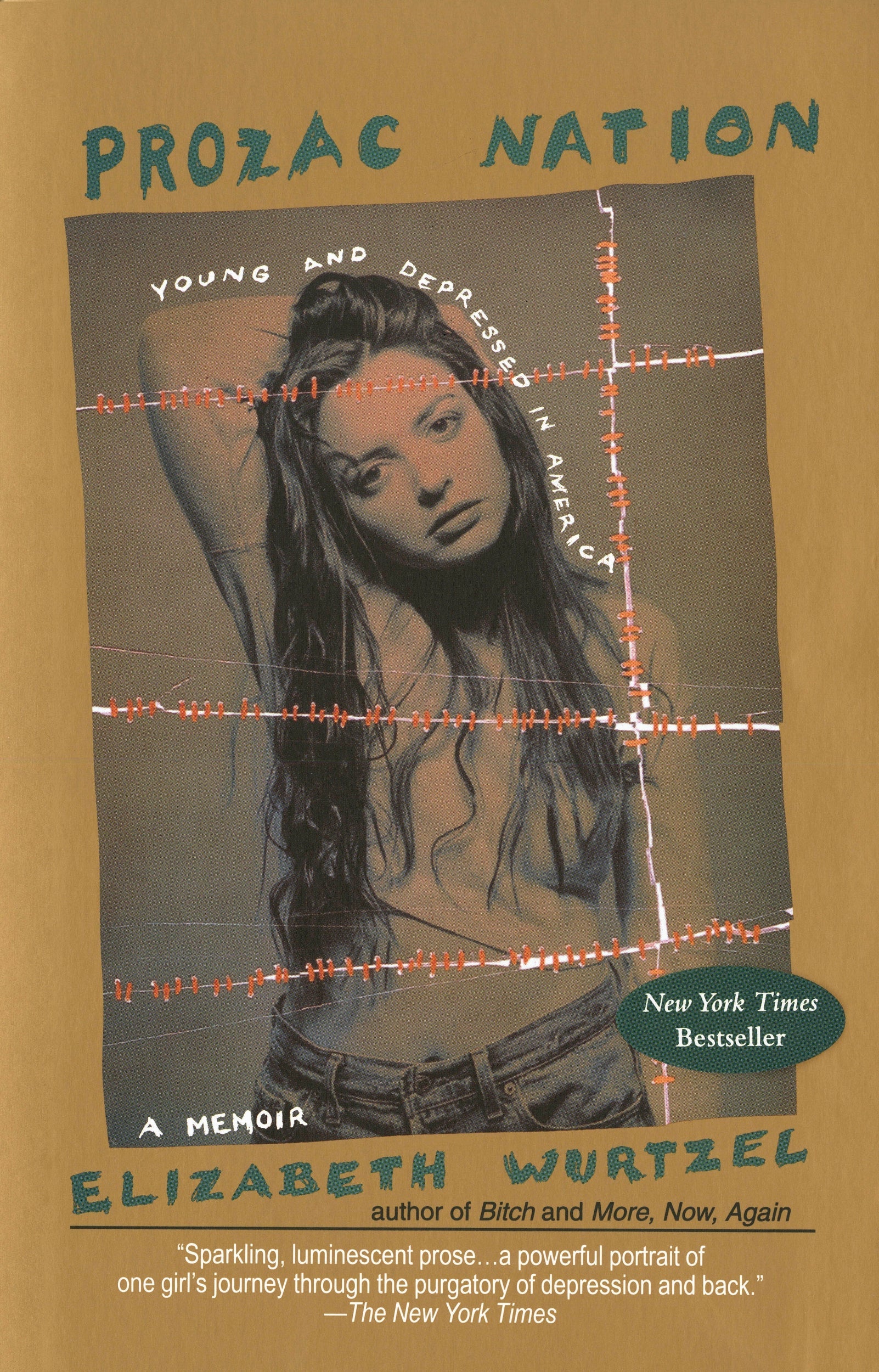

Her harrowing debut, Prozac Nation: Young and Depressed in America (1994), established her as one of the most provocative writers of her generation, generating awe among readers who saw in her work an honest depiction of depression and mental health issues, as well as derision from some critics who accused her of self-absorption, narcissism and relentless self-promotion.

The book took its name from an antidepressant that she was one of the first to be prescribed, and drew comparisons to William Styron’s memoir Darkness Visible (1990), which had kickstarted a national dialogue surrounding depression, and Susanna Kaysen’s Girl, Interrupted (1993), which recalled the author’s mental health struggles as a young woman in the 1960s.Wurtzel was decades younger that Styron and Kaysen, and far more explicit in her descriptions of razor blades that she used to slice up her legs at age 11, sex acts that left her with chapped lips, and a “black wave” of depression that led to a suicide attempt. Its description of a young woman’s messy, emotionally torturous journey into adulthood was later viewed as a precursor to television shows such as Girls, created by Lena Dunham.

Wurtzel went on to make “a career out of my emotions”, as she later put it, receiving a reported $500,000 advance for her second book, the essay collection Bitch: In Praise of Difficult Women (1998). For the cover photo, she posed topless, sneering at the camera and raising a middle finger; the opening pages included scathing quotes from reviewers, in addition to the usual round-up of praise.

By then, Wurtzel’s life had been upended by cocaine, heroin and other drug use, including crushing and snorting 40 tablets of Ritalin a day. In her memoir More, Now, Again (2002), she recalled smuggling cocaine into Scandinavia through her diaphragm and enlisting her drug dealer to send “an eightball of coke” via FedEx.

Those misadventures came to an end in 1998, when Wurtzel said she stopped using drugs, aside from the antidepressants that she credited with keeping her alive. Within a decade, she also launched a new career, graduating from Yale Law School and working for several years at the white-shoe firm of Boies Schiller Flexner.

The 9/11 terrorist attacks had left her feeling “powerless” and unable to write, she said, explaining her decision to become a lawyer, although elsewhere she said she simply went on a whim. But her writing never stopped – and, as it had from nearly the beginning of her career, her own life remained a focus.

In a 2018 essay for New York magazine, she wrote of discovering that her father was not Donald Wurtzel, as she had believed for 50 years, but in fact photographer Bob Adelman, a leading chronicler of the civil rights movement. “Life,” she wrote, “is just a shock to the system.”

Elizabeth Lee Wurtzel was born in Manhattan in 1967. Her mother, Lynne Winters, was an assistant at Random House when she had an affair with Adelman, according to Wurtzel. He remained a family friend, lived a block away and died in 2016. (Wurtzel said it was only after his death that she learnt of their relationship.)

She described her other “father” – Donald Wurtzel, an IBM data analyst – as “hard to reach,” and said that she spent years trying to make sense of their relationship, “in writing and therapy and conversation, with cocaine and heroin, with recovery and perseverance, and with my thoughts”. She was two when her parents divorced.

A precocious writer, she began putting together short books about pets at age six, adapted Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” into a play, and studied at the Jewish day school Ramaz. She also faced crippling depression that sometimes left her unable to get out of bed.

Wurtzel graduated from Harvard College in 1989, after receiving a college journalism award from Rolling Stone for her stories in the student-run Crimson newspaper. She was fired from a Dallas Morning News internship amid accusations of plagiarism but soon found work as a music critic, and began turning an unpublished 20,000-word article about Harvard into a personal account of depression. Originally titled “I Hate Myself and I Want to Die”, it was changed to Prozac Nation at the insistence of her editor, and adapted into a 2001 movie starring Christina Ricci.

Wurtzel also published an advice book, Radical Sanity (1999, later known as The Bitch Rules and The Secret of Life). After receiving her law degree in 2008, she wrote about intellectual property law in the 2015 book Creatocracy.

She is survived by her husband Jim Freed, whom she married in 2015 but from whom she separated in 2019.

Elizabeth Wurtzel, author, born 31 July 1967, died 7 January 2020

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments