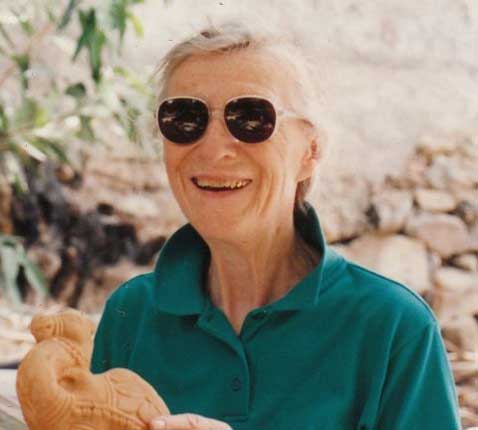

Elizabeth Eames: Influential, widely published archaeologist whose expertise was in medieval floor-tiles

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1949 Elizabeth Eames became Special Acting Assistant Keeper in the Department of British and Medieval Antiquities in the British Museum. She had been appointed to unwrap and catalogue the department's collections, which had been sent away to safe places for the duration of the Second World War. But before long she was invited to work on the collection of medieval floor-tiles that the trustees had acquired, with a grant from the National Art Collections Fund from the Duke of Rutland in April 1947 to augment the not inconsiderable collection already in the museum.

Writing in the Archaeological Newsletter for October 1948, Rupert Bruce-Mitford discussed progress in medieval archaeology, referring to a landmark in the subject, the London Museum Medieval Catalogue, to Gerald Dunning's work on medieval pottery – and to the British Museum's plans to publish a catalogue of its medieval tiles, so recently enlarged by the acquisition of the Rutland Collection. He remarked that with these works "the foundations of medieval archaeology will have been well and truly laid".

By the 1960s Eames's domain was a tiny room at 1a Montague Street, with a desk, filing cabinet, bookcase and a phone, which she disliked using. In the basement were three rooms, with racks and low-drawered mahogany cabinets containing the largest and most important collection of medieval floor-tiles in the world.

The Rutland acquisition included the Canynges pavement from Bristol, pieces of pavement from Halesowen, West Midlands, part of a pavement from Burton Lazars, Leicestershire, tiles from Byland Abbey, Yorkshire, from the tile-kiln at Bawsey, Norfolk, and masses of tiles from the abbeys at Hailes, Chertsey, Rievaulx and Maxstoke Priory. Already in the museum's collection were more than 3,000 tiles from Chertsey Abbey and the decorated wall-tiles from Tring, Hertfordshire.

The list of material demonstrates the enormous diversity and quality of tiles that Eames had to study and understand. Nothing had been published properly and questions about the techniques of production had never been raised. Eames had to start from scratch, acquiring an unsurpassed knowledge of the literature.

She did so with alacrity, publishing many seminal papers and contributions to articles, as well as her own Medieval Tiles: a handbook (1968), followed by English Medieval Tiles (1985) and English Tilers (1992). She established a thorough academic approach and made this neglected subject her career, transforming the study of floor-tiles over the whole of Europe. The British Museum's collection was finally published in 1980 as the two-volume Catalogue of Medieval Lead-Glazed Earthenware Tiles in the Department of Medieval and Later Antiquities, British Museum – with 14,000 tiles listed and illustrated with more than 3,000 designs.

She was born Elizabeth Graham in Northampton in 1918, the eldest child of Fred Graham, a research chemist, and his wife Eva. After Rugby High School she went to Newnham College, Cambridge (the first pupil from her school to win a place at the university) and there read English for part II, before changing to Archaeology and Anthropology. Following war service in the ATS, she gained an MLitt – on women in Viking society – from Cambridge in 1950, having studied at the University of Oslo in 1947-48. She joined the British Museum in 1949, the same year that she married Herbert Eames, a solicitor and later a Conservative councillor in Lewisham, south-east London.

Much of Elizabeth Eames's work was delivered as lectures to the Society of Antiquities of London (she was elected a Fellow in 1958), or to the British Archaeological Association, which she had joined in 1950, and in whose journal she published regularly. She was a member of the BAA's council for three terms, serving for 17 years, and was elected vice-president in 1978.

In preparing the BM catalogue, Eames engaged many young illustrators, who had to meet her rigorous standards, although, surprisingly, she never published any of her own drawings. For more than 40 years anyone who had floor-tiles to discuss went to see Eames. Welcoming, always, generous with time and information, she was the fulcrum of medieval-tile studies.

I nervously went to see her in 1966, having become interested in some tiles from North Devon. Eames was stunningly encouraging, urged more field work and research and then suggested that the result should be submitted for an essay prize. Floor-tiles studies have remained for me an interest ever since. And I am only one of several students whose work was greatly influenced by Elizabeth Eames.

In her publications there is scarcely a county in England which does not have a note or article. On a wider academic front she was well respected and known overseas. So much so that a small seminar held in the British Museum in March 1983, to mark the publication of her catalogue, was attended by fellow scholars from France, Germany, Denmark, Ireland and Holland. Significantly, catalogues of tiles from Germany and Denmark are modelled on Eames's BM catalogue, and with Tom Fanning she produced an important corpus of Irish medieval tiles, published in 1988.

During her career she supervised or helped with excavations on medieval kilns at Meaux Abbey, Yorkshire (1957-58), Clarendon Palace in Salisbury (1967-68) – organising the lifting of two pavements and the kiln itself to the British Museum – Ramsey Abbey, Cambridgeshire (1967-68) and Haverholme Priory in Lincolnshire (1970). In the early 1970s she created a new gallery at the museum to display the collection of tile pavements and kilns.

Eames, with Dr A.B. Emden, with support from the British Academy, established the Census of Medieval Tiles in Britain in the late 1960s, engaging a large number of field workers to assemble material from the English counties. Census volumes for Dorset and Wales have been published and similar volumes for Somerset and the whole of northern England have also appeared. Without Eames's impetus, these volumes and many other publications by specialists would have been impossible.

But Eames's contributions to medieval studies were not confined to her work on floor-tiles. Throughout her busy personal and family life she worked assiduously for the City Literary Institute, London University Department of Extra Mural Studies, the City University and the WEA (London District). For more than 45 years she taught a wide variety of courses, which were frequently oversubscribed. She commanded great respect and the admiration of thousands of students.

Eames was president of the Surrey Archaeological Society, and the Southwark and Lambeth Archaeological Society; she served as governor of special-needs schools in the London borough of Lewisham and was associated with the Horniman Museum for many years.

Elizabeth Sarah Graham, archaeologist: born Northampton 24 June 1918; Special Acting Assistant Keeper, Department of British Archaeology 1949-80; MBE 1978; married 1949 Herbert Eames (died 1983; one son, two daughters); died Hampstead, London 20 September 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments