Ekaterina Maximova: Russian ballerina whose physical virtuosity and expressive gifts won her a worldwide following

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The news of Ekaterina Maximova's sudden death, issued by the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, was greeted with shock by her colleagues and admirers. Some of them had seen her just hours before at the Bolshoi Theatre and she had seemed on top form.

Born in Moscow 70 years ago, on 1 February 1939, the daughter of an engineer (her father) and a journalist and editor (her mother, still alive, aged 91), she became one of the greatest ballerinas of the 20th century, loved the world over. Part of her fame rested on the fact that she was one half of a glamorous partnership on- and off-stage with Vladimir Vassiliev, arguably the most exciting male dancer of the Soviet regime, the USSR's answer to the departed Rudolf Nureyev. They were ballet's most romantic couple. Yet, just as Vassiliev forged his own career as choreographer and director, she also found enormous independent success right from the start of her career. Elfin, she was nicknamed "the miraculous little elf" and "the baby of the Bolshoi Theatre" on the company's American tours, yet she combined her physical virtuosity with an expressive gift worthy of the best in spoken drama. Her range was remarkably wide, from the exuberant wit of Kitri (in Don Quixote) to the romantic spirituality of Giselle, from the strict classicism of The Sleeping Beauty to Soviet epics and experimental works.

From earliest childhood Ekaterina – "Katya" – Maximova had wanted to dance and she persuaded her mother to take her to audition for the Moscow Choreographic School (the school affiliated to the Bolshoi Ballet). She entered the school in 1949, where her teacher in her eighth and final year was the celebrated ballerina Elizaveta Gerdt. In that same year she was chosen to dance the young Masha in the Bolshoi Ballet's Nutcracker.

On graduating in 1958, she was accepted into the Bolshoi Ballet and there, only one year later, she created the leading role of the young, innocent Caterina in Yuri Grigorovich's Moscow production of The Stone Flower. Grigorovich was then emerging as a fresh, revolutionary voice in Soviet choreography and later, as artistic director of the Bolshoi Ballet, he would go on to create many of his signature ballets and productions on Maximova: she was once more Masha in his version of The Nutcracker 1966), Princess Aurora in his Sleeping Beauty (1973) and most memorably Phrygia, the wife of the titular slave-rebel in Spartacus (1968).

In 1959 she took part in her first American tour where, despite her junior status, she was enthusiastically singled out by the press. In 1960, after just two years in the company, she danced Giselle – at that time the youngest dancer to take on this major classical role. Galina Ulanova, the greatest of all Soviet ballerinas, had just retired from the stage, and she coached Maximova in the part. Maximova thus became her first "student", the beginning of an enduring mentoring relationship.

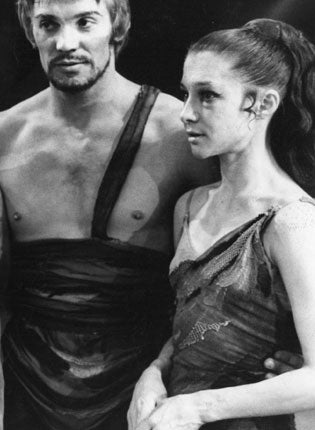

Although during her career Maximova had many stage partners, her closest partnership was with her husband Vassiliev. They had first danced together in the second-year class of the ballet school. In Grigorovich's Stone Flower Vassiliev was Danila, the young man loved by and loving Maximova's Caterina. In 1960 Kasian Yaroslavich created Fantasia (to music by S. Vasilenko) for the young couple. And when in 1969 the Bolshoi came to London, Maximova and Vassiliev in Spartacus – thrilling, emotional – almost stopped the audience's collective heart. While Vassiliev as Spartacus astonished audiences by his virile charismatic athleticism (he was a quintessential product of the heroic Moscow style), Maximova was unforgettable in the ballet's neck-breaking lifts and her expressive power.

When relations between Grigorovich and members of the company, including Maximova and Vassiliev, soured, Maximova fulfilled her maxim: "It's not important where you dance, it's important that you should dance." She danced round the world: at the Milan Scala, at the Paris Opera, at the Met in New York, at the Colon in Buenos Aires. She appeared with Ballet of the 20th Century in Béjart's Romeo and Juliet, partnered by his leading man Jorge Donn (1978). She danced with Roland Petit's Ballet de Marseille in The Blue Angel (1987). She appeared in London with English National Ballet, dancing Tatiana in John Cranko's Onegin (1989). She was in Chicago with the Joffrey Ballet, in Round of Angels (1994), made for her by Gerald Arpino as an anniversary gift. Her last performance, aged 60, was in the United States, in Martha Clarke's Garden of Earthly Delights.

She also diversified in Russia, appearing with the Moscow Classical Ballet, founded by Natalia Kasatkina and Vladimir Vasiliov (not Vassiliev!). In 1981 she danced in their Romeo and Juliet and travelled with them to London to appear in Pierre Lacotte's 1980 recreation of Filippo Taglioni's Natalie and the witty Kasatkina-Vasiliov Creation of the World (to Darius Milhaud's score) where she was Eve.

Meanwhile Vladimir Vassiliev turned increasingly towards choreography, creating many ballets for Maximova and himself such as Icarus (1971/1976), Anyuta (1986) and Cinderella (1991). Anyuta was based on a short story by Chekhov and first shown as a television film. Eventually they formed their own touring ensemble, returning to Moscow in 1995 when Vassiliev was named overall director of the Bolshoi Theatre, a post he held until 2000.

She appeared not only in television documentaries, but in many feature films as a straight actress and made-for-television ballet films, created on her and winning international prizes. These included Dmitri Briantsev's Galatea (a version of George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion) in 1978 in which she played Eliza Doolittle (the film won a BBC prize). Most vivid, perhaps, was her central role, as a Chaplinesque urchin and beautiful woman, in Old Tango, also by Briantsev, for which she won a "Best Female Performance" at the 1980 Prague International Festival.

For someone with a wide smile and luminous eyes that reached far across the orchestra pit, she seemed an unlikely candidate for depression, but she suffered bouts throughout her life. To all who worked with her she was known as Madam Nyet, because whenever she was first approached with a proposal, her first reaction, thinking she couldn't succeed, was "No!"

After retiring she became a coach at the distinguished RATI (the Russian Academy of Theatre Arts), at the Kremlin Ballet and from 1998 at the Bolshoi Ballet. She said she wanted her students – who included the prima ballerina Svetlana Lunkina – to dance better than her. She was the recipient of many honours and the subject of many books and in 2003 wrote (with Elena Fetisova) her autobiography Ekaterina Maximova: Madam Nyet.

Nadine Meisner

Ekaterina Sergeyevna Maximova, ballerina and teacher: born Moscow 1 February 1939; married Vladimir Vassiliev; died Moscow 28 April 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments