Edward Lewis: Film producer who helped to break the Hollywood blacklist

He hired a banned writer for the epic ‘Spartacus’ in a move that sounded the death knell for the Cold War-era witch-hunt

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When movie producer Edward Lewis hired screenwriter Dalton Trumbo to write the epic Spartacus, he struck a blow against the Cold War-era blacklist, under which scores of purported communists and left-wing sympathisers were barred from work.

In a career that stretched back to the late 1940s, Lewis, who has died aged 99, wrote occasional film scripts, produced 20 episodes of the TV anthology series Schlitz Playhouse of Stars, and worked with leading directors such as John Frankenheimer (Seven Days in May), John Huston (The List of Adrian Messenger) and Louis Malle (Crackers). He also shared an Oscar nomination with his wife Mildred for producing the 1982 hit Missing, about the death of an American writer in Chile.

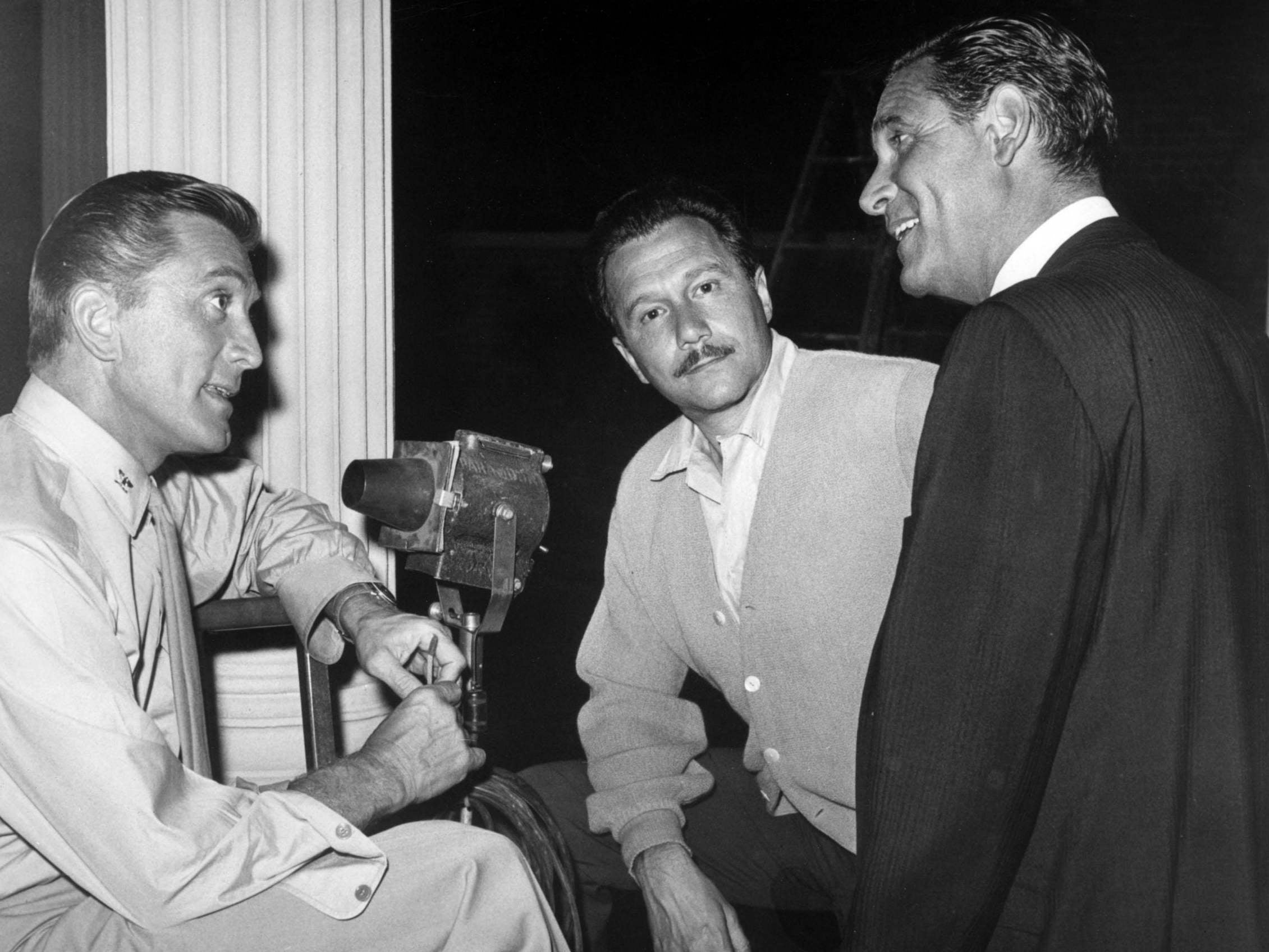

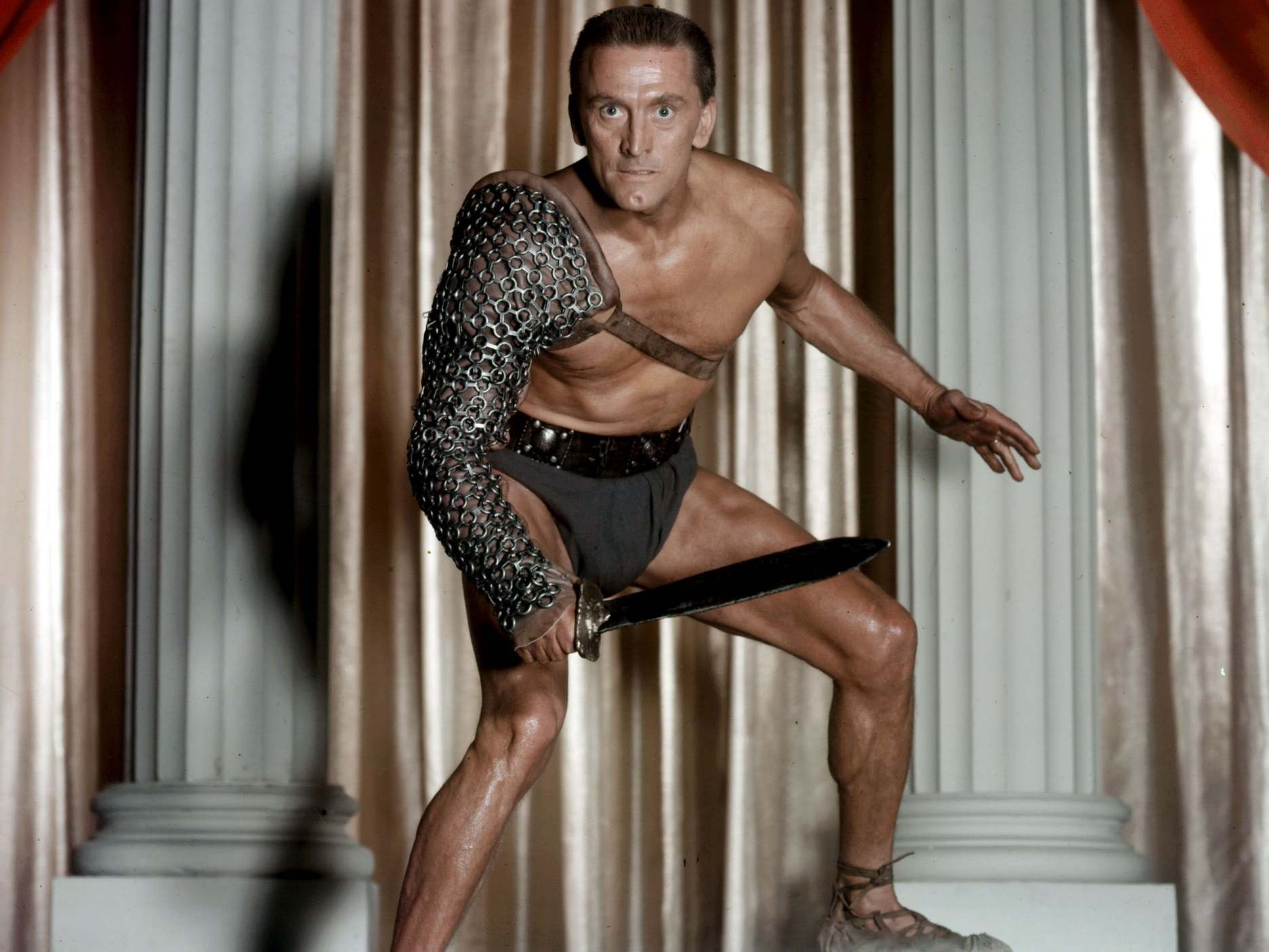

His movies earned 21 Oscar nominations, including six for Spartacus (1960), a swords-and-sandals epic directed by a young Stanley Kubrick and executive-produced by Kirk Douglas, who also starred as the title character, a gladiator who leads a slave revolt in ancient Rome.

Adapted from a novel by Howard Fast, which Mildred read and recommended her husband produce, Spartacus was one of the most expensive films of its time. It received mixed reviews upon its release but became a fixture of late-night television and, because of its script by Trumbo, was credited with helping to bring down the blacklist. Since the late 1940s, blacklisted writers had left the country, switched fields, written under assumed names or used sympathetic producers as “fronts”.

Among the most vaunted incognito scriptwriters was Trumbo, a member of the Hollywood Ten who served a brief prison sentence after being held in contempt of congress, then wrote Oscar-winning screenplays for Roman Holiday and The Brave One. Neither bore his name.

But in January 1960, director Otto Preminger announced that his upcoming epic Exodus – released by United Artists, which had not signed a pledge to bar communists from its films – was written by Trumbo. Months later, Universal-International followed suit with Spartacus. Douglas claimed credit for hiring Trumbo and striking the decisive blow against anti-communist hysteria in Hollywood. But others said it was Lewis who directly commissioned the writer.

Serving as a front for Trumbo, Lewis had his own name printed on the cover of the script. By his account, he waited until it was too late for Universal to cancel the film, then told the studio: “Take my name off the script.”

Lewis produced five more scripts written by Trumbo, including The Last Sunset (1961) and Lonely Are the Brave (1962), both Westerns for Douglas’s production company. According to a 2015 biography of Trumbo, the screenwriter later wrote that Lewis “risked his name to help a man who’d lost his name”.

Edward Lewis was born in Camden, New Jersey, in 1919. A grandfather ran a furniture business that employed his father, and his mother was a homemaker. At 16, he entered Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. He apparently did not receive a bachelor’s degree before starting dental school, which he later quit to become a captain in the army. He ran a military hospital in England during the Second World War before settling in Los Angeles, where he met Mildred Gerchik, the sister of an old army buddy.

He soon persuaded her to cut off her engagement to another man, and they married around 1946, embarking on entrepreneurial ventures that included an unsuccessful pet health insurance company. But they also knew people in the film industry and struck on the idea of adapting a Balzac play for a movie. The idea worked, and The Lovable Cheat (1949), marked Lewis’s first foray into producing.

In addition to Seven Days in May (1964), a political thriller starring Burt Lancaster and Douglas, Lewis was producer or executive producer of eight other films with Frankenheimer, including Seconds (1966), Grand Prix (1966) and The Iceman Cometh (1973), based on the play by Eugene O’Neill.

Lewis and his wife, who served as the executive producer of Hal Ashby’s comedy classic Harold and Maude, backed the civil rights movement in Los Angeles. They also sought out work with a social or political edge – notably Brothers (1977), which they co-wrote, based on the relationship between black activists Angela Davis and George Jackson.

Their film Missing (1982), directed and co-written by Costa-Gavras, was based on the story of Charles Horman, an American writer and filmmaker who was living in Chile when he disappeared and was killed soon after a 1973 coup. Starring Jack Lemmon and Sissy Spacek as Horman’s father and wife, it was nominated for four Oscars but lost to Gandhi for Best Picture.

Lewis also partnered with impresario David Merrick to produce One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, a 1963 Broadway adaptation of the Ken Kesey novel, and shared an Emmy nomination as executive producer of The Thorn Birds, a 1983 hit miniseries about a family living at a sheep station in the Australian outback.

After co-producing The River (1984), about a Tennessee family trying to hold on to their farm, Lewis shifted his attention to writing projects, including novels, stories, plays and a musical, The Good Life. The show featured music by Randy Edelman, who wrote the score to movies including Executive Action (1973), a speculative account of the Kennedy assassination produced by Lewis.

“The main character is a man who’s principled, believes in things – and at 70, remains a militant, optimistic person, involved in what’s going on in the future,” Lewis said after the show’s Hollywood premiere in 1987. “And you know, that’s been the theme of my own life. I’m bothered by the cynicism and negativity everywhere today. I’m an optimist: I believe there can be a good life.”

His wife Mildred died in April. He is survived by two daughters.

Edward Lewis, film producer, born 16 December 1919, died 27 July 2019

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments