Edgar Hilsenrath: Novelist and Holocaust survivor who turned tragic into comic

In humour the German writer found a platform to make sense of the experiences he endured as a child and relay them to the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Edgar Hilsenrath was the Holocaust survivor who drew outrage and admiration with his dark satirical takes on life in the ghettos and the horrors of genocide.

The black comedy of novels such as 1971’s The Nazi and the Barber – told from the standpoint of an SS officer – drew on his teenage years Liepzig, in a shtetl in Romania, and the Ukrainian ghetto he spent the war years in.

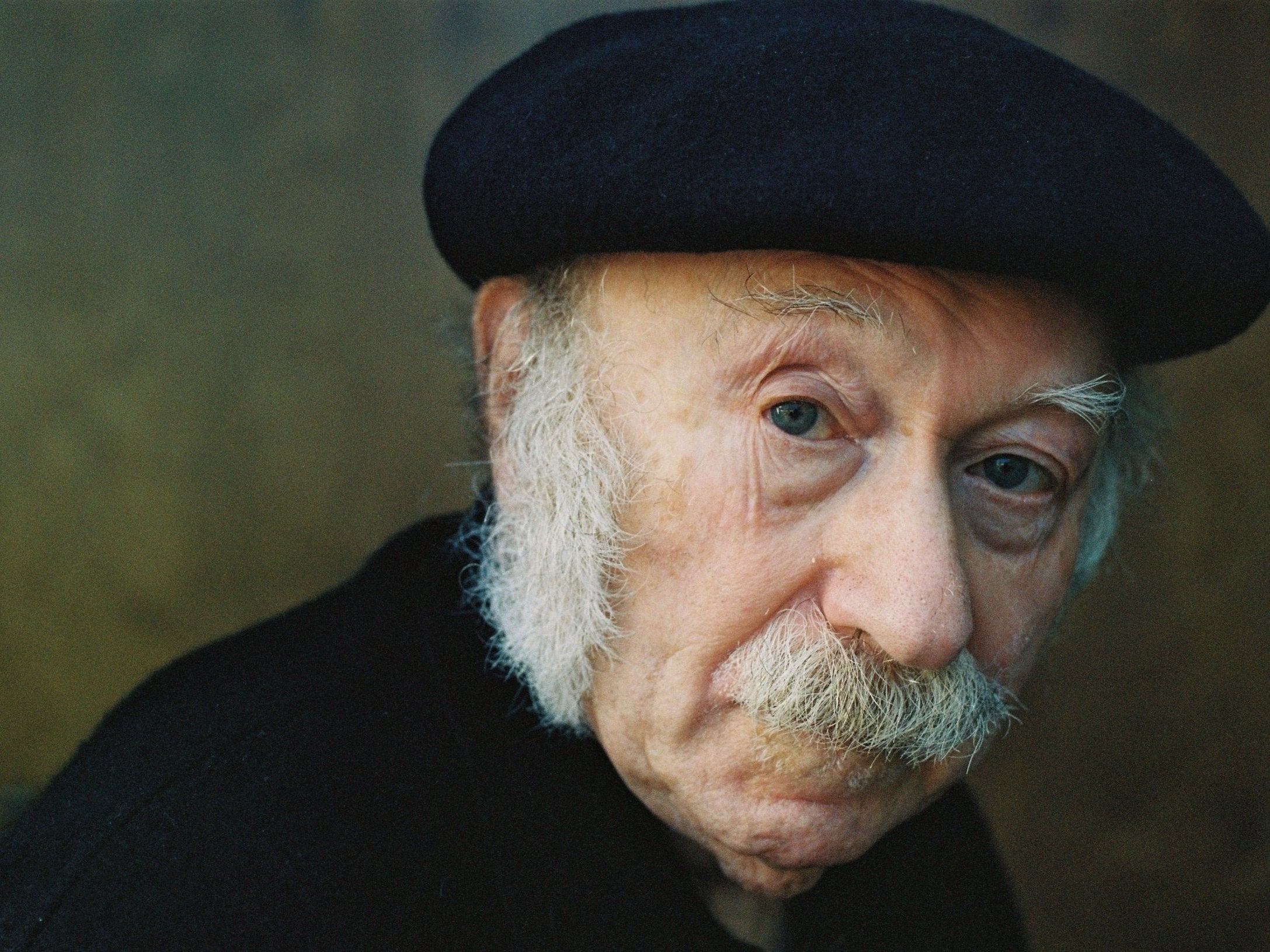

Known for his laconic manner and trademark beret, Hilsenrath, who has died aged 92, sold millions of books and was translated widely.

While other works focused on the determination of its survivors or the heroism of rescuers, novels such as Night, A Novel, his 1964 debut, focused almost entirely on the agony of victims.

Completed while Hilsenrath was working as a waiter in New York, Night centred on Ranek, a Jewish man forced to live in a ghetto modelled on the one in Ukraine where he, his mother and his brother were sent in 1941.

Unlike his family’s relative comfort, Ranek slept under a table, had to barter for food, and used a hammer to extract a gold tooth loose from his dead brother’s jaw. Other ghetto prisoners were forced eat rubbish.

“I felt guilty because I survived,” he once told Der Spiegel, explaining why he decided to amplify Ranek’s suffering.

Not content with the depiction of Jews as victims, Night also featured Jewish characters who rape women causing outrage in West Germany.

“The Jews in the ghetto,” he said, “were every bit as imperfect as human beings anywhere else.”

Max Schulz, the protagonist of The Nazi and the Barber, is a war criminal who escapes prosecution by adopting the identity of one of his concentration-camp victims – a Jewish friend from his childhood – and moves to Israel where he becomes a war hero and hairdresser.

In a closing scene, he confronts God, declaring that inaction from the divine was partly responsible for the Holocaust. The scene was deleted from the German-language edition, because Hilsenrath did not want it to seem absolving of the German people’s collective guilt.

Initially rejected by 60 German publishers, the book won a critical boost from Nobel Prize-winning writer Heinrich Böll, who praised its “gloomy and quiet poetry”, while noting that he had to overcome a “threshold of disgust”.

“Sensitive readers do have problems with my books,” Hilsenrath said in 2005.

His 1989 book, The Story of the Last Thought, cast a gaze of look and despair on the Armenian genocide of 1915 to 1917. He told Der Spiegel of an Armenian friend’s response: “[She was] totally horrified. She had just read the part about the 97-year-old man that sleeps with a Kurdish nine-year-old girl and said she could not go on reading the book. That’s how it is with my books.”

Edgar Hilsenrath was born in Leipzig in 1926 and raised in the nearby city of Halle, also known as Saale. As antisemitic attacks escalated in Germany, the family decided to flee. In 1938, Hilsenrath’s father, a furrier, told the family he would eventually meet them in Paris.

His mother took Hilsenrath and his brother to her native Romania, where they lived in the town of Siret, just across the border from Ukraine.

In 1941 the family was deported, taken by cattle truck to a ghetto in Mogilev-Podolsk, Ukraine. Defying the rules of the ghetto, they sewed jewellery and other valuables into their clothing, then traded them for food with nearby farmers. Hilsenrath recalled receiving a death sentence after being caught trying to escape. He said he “stood facing the firing squad for about 10 minutes” before “the order to shoot was rescinded”.

By late 1944, the ghetto was liberated by Russia, and Hilsenrath made his way back to Siret, where a group of Zionists from Bucharest invited him to settle in British-controlled Palestine.

He lived there for several years before moving to France, where he reunited with his father and the rest of the family, determined to become a writer.

Hilsenrath’s idiosyncratic brand of gallows humour was developed after the war, he once told German radio, “because it was the only way to deal with all the bad memories”.

He moved to New York in 1951 – his experiences satirised in 1980’s Fuck America – and returned to Germany in 1975 where neo-Nazi protestors interrupted one of his readings, amid of resurgence of antisemitic attacks.

His wife Marianne predeceased him. Survivors include his second wife, Marlene Hilsenrath, whom he met at a symposium on his work.

Edgar Hilsenrath, writer, born 2 April 1926, died 30 December 2018

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments