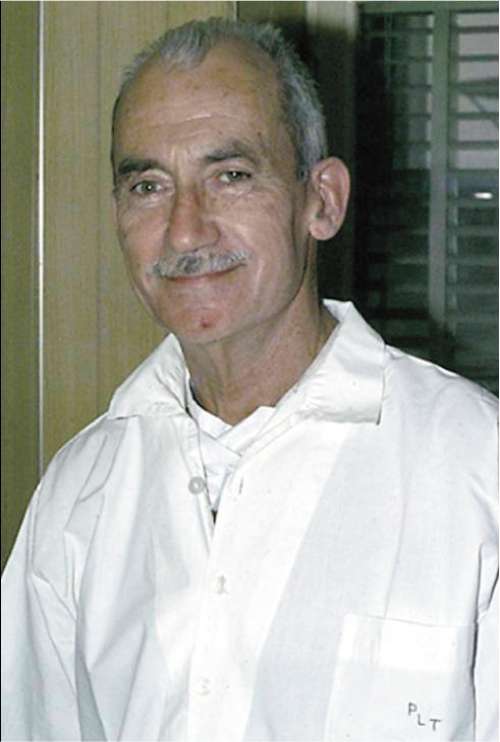

Dr Paul Tessier: Plastic surgeon who revolutionised the treatment of facial deformity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Paul Tessier was a great innovator in the medical profession, the creator of a new surgical speciality which brought hope to many with severe facial deformities that had previously been untreatable. He is acknowledged as the father of craniofacial surgery and his contribution is recognised internationally, crossing the boundaries of the related specialities of plastic, maxillofacial, ophthalmic and neurosurgery.

His techniques unlocked the face and skull to allow complex remodelling. He was never content that a patient should "look better than they did before we started". His philosophy was "if it is not normal it is not enough". The power of Tessier's surgical techniques and his results gave birth to craniofacial centres worldwide, and influenced fields as disparate as facial aesthetic surgery and skull base cancer surgery.

Paul Tessier was born in Heric on the French Atlantic coast in August 1917 into a family of wine merchants. He entered medical school in 1936, having considered careers in forestry and the navy, from which he was excluded by early ill health. He was interred as a prisoner of war in 1940, and became critically ill with a typhoid infection of the heart, a diagnosis made by his former professor but expediently credited to his captors. Perhaps this influenced his release in 1941, whereupon despite advice to rest he took up rowing. This response to adversity was fundamental to his later successes.

Tessier became interested in facial form and deformity when introduced to plastic surgical techniques of cleft lip and palate repair in Nantes in 1942. The following year he escaped death for the second time. He was to have been surgical resident on duty the afternoon of an American bombing raid which destroyed his on-call room and killed his deputised colleague – but for the invitation of his tutees to a celebratory picnic on the river.

The destruction of Nantes prompted a move to Paris and a short-lived administrative post which held no attraction. He then left a post as a steelworks medical officer for the paediatric service at Hôpital Foch in 1946, where he was later to undertake his groundbreaking work.

He began making trips to England where rapid advances in plastic surgery in response to severe military injuries were evolving in the hands of Sir Harold Gillies and Sir Archibald McIndoe – "It was a revelation," he recalled. A fondness for England was kindled and, decades later, he was to develop a relationship with the nascent craniofacial unit at Great Ormond Street Hospital, remaining visiting professor into the 1990s.

By the mid 1950s Tessier had become the head of his department in Paris, and was consulted in 1957 by a young man with a facial deformity of "monstrous aspect", the like of which he had not previously seen. His subsequent research led to the diagnosis of Crouzon syndrome in which there is poor development of the upper jaw and eye sockets, leading to bulging eyes and breathing obstruction. Gillies had previously tried an operation to move the whole upper jaw and lower part of the eye sockets forward but had commented to others "never to do it".

Tessier set about problem-solving by anatomical study on dry skulls, but was denied access to the anatomy room by the Paris medical establishment. Characteristically undiscouraged, he travelled by evening to Nantes for late-night cadaveric dissections, returning in the early hours for the next Parisian working day. His painstaking preparatory work was the mark of the man. Tessier successfully advanced his patient's face by 25mm, achieving stability by the novel use of bone graft.

This achievement was immense, particularly given that Tessier had, for reasons of a historic dispute between plastic and maxillofacial services at Foch, been refused co-operation by the orthodontic department which produced the splints that were hitherto required for maintaining facial stability after trauma. Tessier's next great advance was to devise a technique for separating the eye sockets from the skull, thereby allowing relocation of the eyeball and protection of vision. Working with the neurosurgeon Gérard Guiot, it took three years to devise the technique, facilitated by making bone cuts from inside the cranium.

These surgeries were so revolutionary that Tessier sought to establish their credentials before continuing, in an invitation symposium in 1967, where cases were demonstrated before distinguished international peers. Word spread internationally and Paris became the birthplace of the new speciality of craniofacial surgery. In response to questions about his approach to problem-solving, Tessier would say, "Pourquoi pas?". This phrase became the motto of the International Society of Craniofacial Surgery, founded in 1983, of which Tessier was invited to be Honorary President.

Paul Tessier's contribution cannot be underestimated. The power to liberate the orbits and the face from the skull has subsequently revolutionised the treatment of craniofacial birth defects, cancers of the orbit and skull base, and severe facial asymmetries. A man shy of applause, Tessier collected many international honours, including the Jacobson Innovation Award of the American College of Surgeons, and the Gillies Lectureship and Gold Medal of the British Association of Plastic Surgeons. He became Chevalier de Légion d'honneur in 2005.

Tessier was an extraordinary man driven by an explorer's desire to overcome difficulty. He was appreciative of sculpture and had a love of hunting, having organised expeditions through uncharted Africa with native trackers for whose skills he had great respect.

Jonathan A. Britto and Barry M. Jones

Paul Louis Tessier, plastic and craniofacial surgeon: born Heric, France August 1917; married (two sons); died Paris 6 June 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments