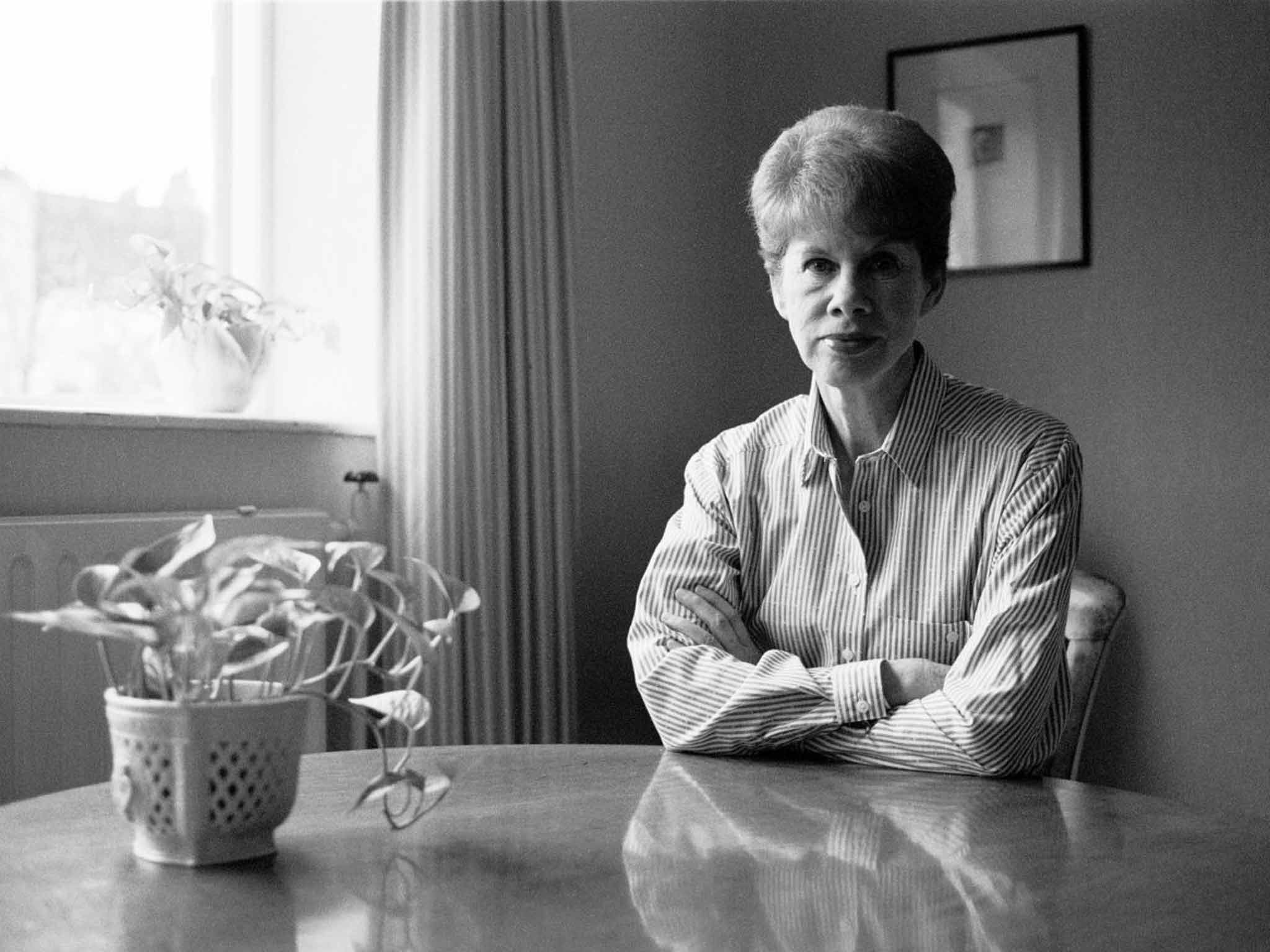

Doctor Anita Brookner: Art historian who began writing novels at the age of 53 and won the Booker Prize for 'Hotel du Lac'

Most of her novels were about lonely women, outsiders, disappointed in love, often betrayed, usually damaged, drawn to “undamaged men”.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“I'm a middle class, middlebrow novelist,” Anita Brookner once said, adding: “It amuses me.” Perhaps the amusement was because the Booker Prize winner had already had one successful career, as a teacher at the Courtauld Institute, when she wrote her first novel at the age of 53.

“Success is integration and total acceptance,” she said. “I felt integrated when teaching, which I loved because it was authentic not made up.” Her novels were “made up” and she consequently regarded them as “displacement activity”. Indeed, she once commented that she wrote to stave off boredom.

She was born in 1928 in Herne Hill, south London, the only child of a Polish immigrant, Newson Bruckner, and Maude Schiska, a professional singer who had toured the United States before her marriage. Fearing anti-German hostility, Anita's mother had changed the family name to Brookner.

In the 1930s Brookner's parents took in her grandmother, uncles, aunts and other German Jewish refugees, some working for them as maids and cooks. All were displaced persons and so, Brookner stated: “everybody was unhappy.”

Unhappiest of all were her parents. Her mother had given up her career to marry but felt she'd married the wrong man. “They were loyal and devoted and all that and both were very unhappy.” On the rare occasions her mother sang her father would get angry “as it was the only time she showed passion”.

The family spoke Hebrew at home but Brookner didn't learn it because her health was “fragile”. Surrounded by all these sad people, she had a lonely childhood. Loneliness would be a theme of her life and her work (when she won the Booker she joked, “I could get into The Guinness Book of Records as the world's loneliest, most miserable woman.”)

Her father was an “extremely virtuous, not very successful” small businessman. “He had a number of enterprises. He had a lending library at one point, I remember, which was, of course, very congenial.” Her father thought Dickens had got the English right. When Brookner was young he gave her Dickens' novels each Christmas and birthday until she had read them all.

When she was old enough she spent Sunday afternoons at the Dulwich Picture Gallery. “The seriousness of the conception” of Poussin's Triumph of David particularly moved her.

She went to the private James Allen's Girls School then King's College, London. She studied French and greatly enjoyed Balzac, Stendhal and, to a lesser degree, Flaubert. Years later a man told her she wrote French novels, “which pleased me enormously.”

She got her BA in 1949 and then a doctorate in art history at the Courtauld. She won a French government scholarship to study at the Ecole du Louvre in Paris. For reasons she didn't explain, Brookner said that her parents disapproved of this and cut her off'

She said later that she was at her happiest in Paris. She came back to teach art history at Reading, and in 1967 she was the first woman to hold the Slade Professorship of Fine Art at Cambridge University. When her mother fell ill, Brookner cared for her until she died in 1969.

In 1977 she was appointed Reader at the Courtauld (invited there by the art historian and spy, Anthony Blunt). She was well regarded as a teacher and cut a distinctive figure: slender, elegantly dressed, smoking untipped cigarettes even in tutorials.

Her first book, published in 1980, was an examination of the life and work of Jacques-Louis David. A year later she published her debut novel, A Start In Life (the title was from Balzac). She explained that she began writing because she had been feeling stale as a teacher and thinking about retirement (she didn't actually retire from the Courtauld until she reached the statutory age of 60.)

The novel – about an unhappy middle-aged woman and her elderly parents - was written “in a moment of sadness and desperation” when her life “seemed to be drifting in predictable channels”. Three years later she won the Booker for her fourth novel, Hotel Du Lac, in which a shy romance writer turns down a boring reliable man in favour of a dashing married one with whom there can be no satisfactory future. “As I wrote it I felt very sorry for her and at the same time very angry.”

She felt all authors wrote the same novel again and again, and certainly by the time of Hotel du Lac she had established the themes she would explore in the rest of her fiction. Most of her novels were about lonely women, outsiders, disappointed in love, often betrayed, usually damaged, drawn to “undamaged men”. In her world “the hare wins every time over the tortoise”.

From 1984 through to 2011 she wrote pretty much a book a year, though she thought she should have stopped with The Latecomers (1988) – “I should have ended it there,” she said. She thought she had won the Booker for “the wrong book”, believing this one to be more deserving.

Until she retired from the Courtauld in 1989 she wrote only in the summer, in her office, when the Institute was closed. She worked a full day and in the evening she would go for long walks through busy London streets.

She bought the flat next door to her own to cope with her large library. After retirement she wrote there. She started writing at 7am each day, in longhand. She wrote “quite easily”, she said, but “lucidity” was “a conscious preoccupation”. In one interview she said that starting and ending was easy, but that what came between was “terrifying”. Even so, she never wrote more than one draft of a novel, although she did spend longer on the last chapter to counter a tendency to rush when she neared the end.

In a 1987 Paris Review interview she said: “writing has freed me from the despair of living. I feel well when I am writing – I even put on a little weight.” She felt she had made a hash of life. She seemed to regard writing as a way of “editing” her own life because she had “started on the wrong footing”.

Later, she said writing was her “penance” because it was such a solitary occupation. She found writing at home “a terrible strain... The isolation weighs on me.” Her isolation was a recurrent theme in the handful of interviews she agreed to throughout her career. Her ambition was “to be unnoticed”; she never appeared at book festivals and if she went to a party it was usually only fleetingly.

She was, she said, lonely for “ideal company”. She got close to marriage several times but had a habit of choosing the wrong people. “At the time it was a cause of great sadness,” she recalled. However, she also said that she had put her career first. She didn't want to be “taken over” by a man, not least because “it would have meant giving up work.” Her greatest sadness was that she had no children. “That's why I write,” she said, though she was adamant her books were not her children.

She said at the time of The Bay of Angels (2001) that she would write all the time if not for a shortage of ideas. The following year The Next Big Thing was Booker-longlisted. She wrote three further novels but then doubted she would write any more because she was bored with her character – with herself. Her last publication, At The Hairdressers, was a novella published as an e-book in 2011.

Whether novel-writing was amusement or not, for her a novel “has to cast a moral puzzle” if it is “to remain pure”. She admired Trollope for his “decent feelings” and George Eliot for her “moral seriousness”. “Anything else,” she concluded, “is mere negotiation.”

Anita Brookner, art historian, teacher and author: born London 16 July 1928; died 10 March 2016.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments