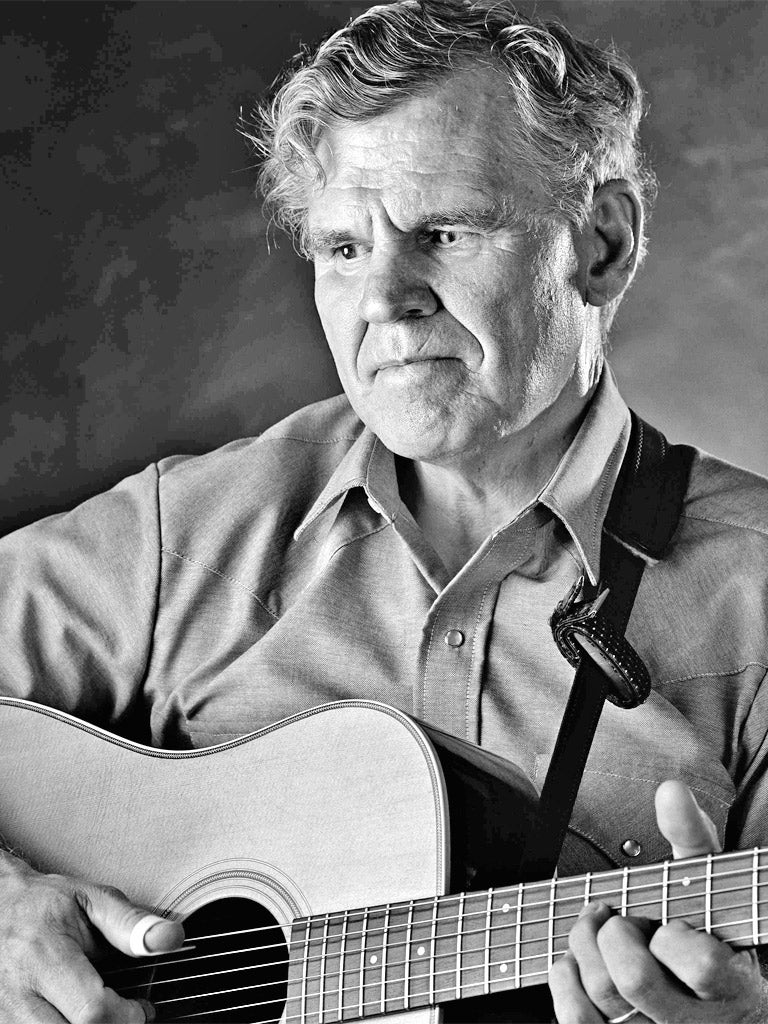

Doc Watson: Guitarist and banjo-player who influenced generations of folk musicians

Doc Watson enjoyed legendary status among American roots musicians. A highly influential guitarist, he adapted many of the fiddle tunes of his Appalachian roots to a new flat-pick idiom. He served, too, as an almost unequalled repository for traditional music, effortlessly handling a repertoire that incorporated not only the folk and mountain music of his childhood, but also blues numbers, gospel songs and even vintage pop material. These achievements were made all the more remarkable by the fact that he had been blind since infancy.

Intensely modest, he possessed a warm, clear baritone voice that exuded sincerity and had an engaging, folksy stage presence that would see him punctuating his performances with stories and witty asides. More importantly, he brought integrity and a clean, crisp quality to his playing that endeared him to fans and fellow musicians. As he noted: "When I play a song, be it on the guitar or banjo, I live that song; whether it is a happy song or a sad song. Music, as a whole, expresses many things to me – everything from beautiful scenery to the tragedies and joys of life."

He was born Arthel Watson in Deep Gap, North Carolina, in 1923. His father, General Dixon Watson, was a farmer who played the banjo and sang in the local church, while his mother sang mountain ballads as she worked around their cabin. He lost his sight as an infant through an eye infection. The family's collection of 78s proved a catalyst in developing his musical sensibilities: "When I began to notice music I was just a little fella. It was everybody from the Skillet Lickers and the original Carter Family to a recording by John Hurt... All kinds of people came up through the years and I listened to all of 'em."

At the age of five he was given his first harmonica, acquiring a new one annually until he was 11, when his father presented him with a home-made banjo, the instrument's head having been sourced from the skin of his grandmother's cat. At 13, and by now attending the Morehead School for the Blind in Raleigh, he borrowed a guitar and taught himself to play the chords for "When the Roses Bloom in Dixieland".

Aware that his son's disability could prove an impediment to prosperity at a time when able-bodied people were barely scratching out a living in the rural South, his father gave him a cross-cut saw so he and his brother could produce lumber for the local tannery. As he recalled: "He made me know that just because I was blind, certainly didn't mean I was helpless." This independent streak led to a fascination with technology that would see him rewiring his own house and assisting family members as they tinkered with their cars. He would later inform audiences that he would doubtless have spent his life as a carpenter, playing music only as a hobby, had he not lost his sight.

He began to perform alongside his brother Linney, drawing upon both the hillbilly boogie of the Delmores and the mountain balladry of the Blue Sky Boys. Appearing on local radio in 1941 he acquired the sobriquet "Doc", a radio announcer having taken a dislike to his given name and opting for something catchier. He absorbed the music of a number of pioneering guitarists and later cited Django Reinhardt and Merle Travis as particular favourites.

In 1951 Watson met the pianist Jack Williams and for the next few years toured North Carolina and Tennessee playing electric guitar in his group, the Country Gentlemen. Although the sets consisted largely of current country hits, western swing and eventually some rockabilly, a demand for square dance tunes led Watson, adapting the fiddle parts, to develop the flat-picking style for which he is renowned. He maintained friendships with older musicians such as Clarence "Tom" Ashley and the fiddler Gaither Carlton – who in 1947 had become his father-in-law – developing a vast repertoire of mountain blues, ballads and dance numbers.

In 1960 he attended a fiddler's convention at Union Grove, North Carolina and met Bill Monroe's manager, Ralph Rinzler, who was sufficiently impressed to arrange gigs at New York folk clubs such as Gerde's and the Gaslight and, in 1963, the Newport Folk Festival. His set at Newport brought Watson to the forefront of the burgeoning folk revival and led to a record deal with Vanguard. He had recorded a couple of albums with Ashley for the Folkways label, but his tenure at Vanguard, coinciding with a partnership with his guitarist son Merle, quickly established him as a major force in old-time music.

He recorded prolifically, with a number of his discs, including Then and Now (1973), Two Days in November (1974), the bluegrass-flavoured Riding the Midnight Train (1987), the gospel-orientated On Praying Ground (1991) and Legacy (2002) netting Grammys. Other notable albums included Red Rocking Chair (1981), Down South (1984), Elementary Doctor Watson (1993) and Docabilly (1995). In 1972 he was one of a number of older performers, alongside the likes of Roy Acuff, Earl Scruggs and Mother Maybelle Carter, who joined the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band in their landmark Will the Circle Be Unbroken project. Other collaborations included Strictly Instrumental (1967) with Flatt and Scruggs, and Reflections (1980) with fellow guitar giant Chet Atkins.

His later years were marred by the death in 1985 of his son Merle following a tractor accident, but with support from guitarist Jack Lawrence he continued to perform and in 1988 founded an annual festival, MerleFest, in Wilkesboro, North Carolina. In time his grandson Richard Watson emerged as the ideal musical foil.

He continued to promote the artistic traditions of the Appalachians and in 2003 released a fine CD/DVD, The Three Pickers, with the banjo virtuoso Earl Scruggs and traditional country singer Ricky Skaggs. He also developed the Folk Art Museum in Sugar Grove, North Carolina and continued to host MerleFest. In 1997 he received the National Medal of the Arts from President Clinton and in 2004 was presented with a Lifetime Achievement Grammy.

When asked how he would like to be remembered, his response was characteristic: "I would rather be remembered as a likeable person than for any phase of my picking. Don't misunderstand me; I really appreciate people's love of what I do with the guitar ... But I'd rather people remember me as a decent human being than as a flashy guitar player."

Paul Wadey

Arthel Lane ("Doc") Watson, musician: born Deep Gap, North Carolina 3 March 1923; married 1947 Rosa Lee Carlton (one daughter, and one son deceased); died Winston-Salem, North Carolina 29 May 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments