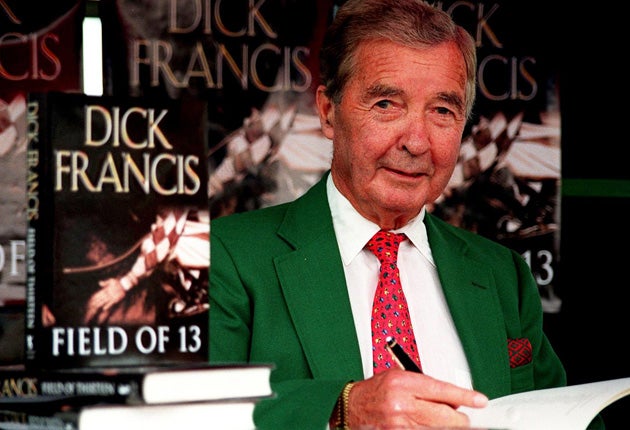

Dick Francis: Champion jockey and best-selling thriller writer

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Dick Francis sampled vivid peril as a bomber pilot and steeplechase jockey. He then gave millions of readers a flavour of his experiences, as author of nearly 40 best-selling adventures – creating a fictional world that could not be dismissed as fanciful, so long as it was measured against his own life.

Francis was, after all, himself victim of perhaps the most startling dénouement in the history of the Turf. Anyone who witnessed his strange misfortune in the 1956 Grand National, riding Devon Loch for the Queen Mother, would know that any plot, any character, can be turned upside-down on the final page.

Having negotiated the big fences with bravura, Devon Loch was clear and just 40 yards from the post when he suddenly sprawled to his knees. It had taken a split-second for Francis to be pitched from exultation to indignity. The grainy image of ESB galloping past Devon Loch splayed helplessly on the ground is one of the most indelible of the sporting century.

Francis himself attributed the horse's behaviour to the patriotic din, an irony that was not lost on him. "I'm afraid it was because of his owner that we lost the race," he reflected in later life. "A quarter of a million people were at Aintree that day, all cheering for the Queen Mother. A crescendo of noise hit him, his hind quarters refused to react for a split second, and down he went."

Whatever the truth, that day brought Francis closer to many future readers, not least the Queen Mother herself. She gave him an engraved cigarette box and a handsome cheque. As it turned out, this was partly intended to cushion his retirement. The following January, Lord Abergavenny, the Queen Mother's racing adviser, summoned Francis and suggested that he quit at the top. The Queen Mother, he said, did not want to see him risking his neck on her novice chasers any more. Francis was shocked. "I nearly threw myself in the Serpentine on my way home," he said. "But I was 36 and knew I wasn't bouncing as well as I had done in the past."

Francis had ridden over 350 winners, enough of them in the 1953-54 season to be champion jump jockey. His finest hour had been the 1949 King George VI Chase at Kempton Park, when Finnure inflicted a first defeat on the Irish champion, Cottage Rake.

Racing was in Dick Francis's blood. His father had been a steeplechase rider, and his grandfather rode in point-to-points. "Give the boy gin," a family friend would always say. "Keep him small." Although this extreme measure was evidently resisted, his father would exasperate his mother by allowing Dick to miss school in order to go hunting in Berkshire.

Aged seven, he listened to the 1928 National on a wireless on his grandfather's Pembrokeshire farm. There were 42 fallers and the race was won by the 100-1 shot Tipperary Tim, the only horse to complete without mishap. Dick Francis vowed that one day he would ride in the race.

Francis liked to say that that his first professional ride had been about that time, when his brother bet him sixpence that he could not stay aboard the farm donkey over a fence, seated facing the tail. Francis fell off six times but ultimately claimed his prize, as you might expect of a rider who would in time break his nose five times, each collarbone six times apiece, an arm, a shoulder, countless ribs. He cracked a vertebra, cracked his skull. At Cheltenham one day he took a hoof full in the face. He had 32 stitches, but rode a winner two days later. His last fall broke a wrist, which he never quite straightened again.

Somehow he would have to adjust to a more sedentary existence. His first written experiments were as racing correspondent of the Sunday Express; his next an autobiography, The Sport Of Queens, published in 1957. "You couldn't call it that nowadays," he would concede as an octogenarian, with typical wryness.

Then, in 1962, there appeared the tip of a publishing iceberg: Dead Cert. During the next four decades it would be succeeded by 37 further adventures, together accumulating 60 million in sales and translated into 35 languages.

Needless to say, there were a few duds, and the standard of the vintage years could not been maintained to the end. But three of them (Forfeit, 1968; Whip Hand, 1979; Come to Grief, 1995) won the Edgar Allan Poe Award, and Whip Hand also the Golden Dagger Award of the Crime Writers' Association. Francis would ritually take the first copy off the press to Clarence House, where the Queen Mother would tease him about his bloodthirsty plots. Philip Larkin was another admirer of these pacy, lucid, cogent tales.

Francis became one of the most cherished popular writers of the 20th century, and one of its richest, too. Every autumn, a new title would be steered to the top of the Christmas book sales while research began on the next one. In the new year, back in Florida and later the Cayman Islands, work would begin on a manuscript, which would be presented to the publishers in early summer in time for a family reunion at the same Devon hotel.

Francis was a great creature of habit. If it seemed like a production line, that suited author and readers alike. The whole oeuvre obeyed a certain formula. Dead Cert was the first of many titles to make menacing play on familiar equestrian vernacular: Blood Sport, In the Frame, Come to Grief, even Slay-Ride. His publishers insisted that Francis did not stray from his home turf, even though each story tended to reflect meticulous research into a parallel world, from art to aviation to accountancy.

The hero would tend to be an outsider, often compromised by responsibility, handicap or hardship. He would be stoical, self-effacing, loyal and courageous, and almost invariably found himself tested in a scene of extreme violence. There would be an answering strength of character in his woman, too, and perhaps that was no coincidence.

Francis never denied that his wife, Mary, had an important role in his work. He often said that he would add her name to the cover if only she would let him. Even so, as he approached 80 he hardly welcomed the sudden accusation of a biographer that Mary had more or less written the books herself. There had long been mutterings about the incongruous second career of a sportsman whose education had been so perfunctory, and the precise contribution of his accomplished, highly cerebral wife.

In his biography, Dick Francis: a racing life (1999), Graham Lord revived a conversation with Mary back in 1980. "Yes, Dick would like me to have all the credit," she is alleged to have told him. "But believe me it's much better for everyone, including the readers, to think that he writes them because they're taut, masculine books that might otherwise lose their credibility."

Although the ageing couple were plainly distressed, ultimately they decided that a calm, weary dignity would allow the matter to fade away – and so it did. They had always maintained that the books were the fruit of a partnership. Nobody now will ever know the exact division of labour, and by the time people began to show an interest, it hardly seemed to matter.

Whatever the truth of their professional collaboration, none could mistake the mutual enchantment of their marriage. Dick Francis had been bewitched from the moment he first saw Mary, standing on the stairs at a family wedding in October 1945, waist-length blonde hair plaited round her head. "For weeks after that I didn't feel the pavement under my feet," he said.

Francis himself was then 25, freshly returned to his horses after the Second World War. He had spent two years in the desert, flown a few sorties over the Channel in a Spitfire, and then transferred to Wellington bombers. They married in the summer of 1947, Francis predictably with his arm in a sling. Because of rationing, Mary had made her dress out of cheesecloth. Having planned a touring honeymoon, in a car given to them by his father, Francis had to teach Mary to drive as they went along.

To their many friends, the Francises seemed no less passionate about each other half a century later. Mary did not enjoy the best of health in later years but retained all her intellectual and social flair. They had two sons, Merrick and Felix, and cherished annual holidays with the grandchildren in Devon and the Caribbean. When Mary died in 2000, her husband was stricken.

Having emigrated chiefly in the interests of Mary's health, they loved their life on Seven Mile Beach. Dick would rise early, take a long walk and a dip in the sea, wash the salt off in the pool. Then he would have a coffee and sit down to work. Their evenings were always gregarious. Once Francis was seated next to the Queen Mother at a Savoy dinner when he started choking. His neighbour summoned water, but Francis declined. "If water rots your boots, what the hell does it do to your stomach?" he said.

When they moved from Florida to Grand Cayman, they were required to prove their intention to live and die in Cayman. As a result, they purchased a plot for their grave. "So we went along to the local council offices and asked to do just that," Francis recalled. "Yes. That was fine. They had some plots left. And then the woman said: 'Oh dear, I'm terribly sorry, we don't have anything left with a sea view'." Somehow he thought he would manage.

Chris McGrath

Richard Stanley Francis, jockey and writer: born Tenby, Pembrokeshire 31 October 1920; Racing Correspondent, Sunday Express 1957-73; OBE 1984, CBE 2000; married 1947 Mary Brenchley (died 2000; two sons); died Grand Cayman 14 February 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments