Denis Mason Jones: Architect and artist noted for his pictorial maps of British cities

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A mention of Denis Mason Jones to any of his wide circle of friends and acquaintances in Leeds would invariably provoke an instant smile. Mason Jones was one of those rare individuals who could move with ease in any number of different circles, and be popular in each, whether it was the Leeds "establishment", the professional set or a jazz night at the Leeds Club.

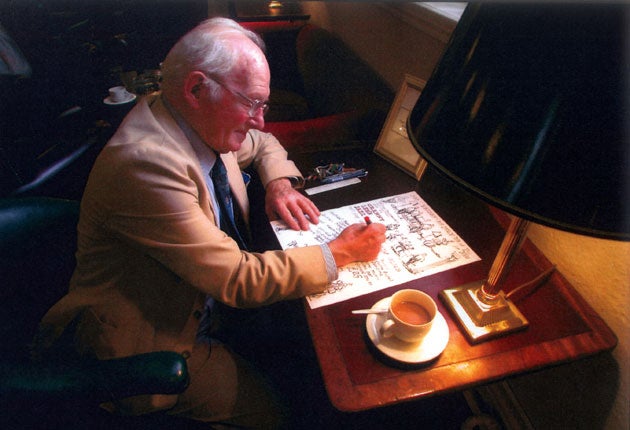

By profession he was an architect, having followed his father into partnership in the family firm. His design for Bodington Hall, at the University of Leeds, won the Leeds Gold Medal in 1964, but although he did many architectural designs, particularly for the conservation and restoration of buildings, one sensed that he much preferred to be occupied in sketching just about everything he was involved in, whether it was the English countryside, historic buildings or a concert he was attending. His jackets were always made with an extra large "poacher's pocket" which contained his ever-present sketchbooks. A junior member of his staff was given the task of cutting pencils into half and sharpening the two pieces for him. He meticulously maintained an archive of these books – amounting to almost one hundred at his death.

To those who knew Mason Jones, his sketches were always recognisable and they had a wider circulation than even he realised. In 1998 when I was on an electoral mission in Cambodia, an American woman based in Laos desperately wanted to come to Phnom Penh as an election observer; when I eventually found a place for her, she brought me a gift of a book, in French, on the English countryside, that she had bought in Vientiane. I immediately recognised the author of the illustrations and when I showed the book to Mason Jones he recalled the occasion when its French author had observed him sketching near Malvern and had made him an offer. "It was one of the few occasions I got paid," he wryly commented.

Mason Jones designed a series of full-colour pictorial maps of British cities featuring their historic buildings. Marketed as "Heritage Maps" they are today much sought-after. Typically, when I got back from a European Union project in Uzbekistan, he presented me with a special map of the Silk Road, portraying the key buildings of Samarkand and Bukhara. In the margin was his pencilled note: "Don't rely on this map for your return to Tashkent!"

He was the quintessential clubman. A member of the Leeds Club for over 40 years, he could regularly be found ensconced in one of its deep armchairs holding court among friends and colleagues. It was one of his great frustrations in recent years that his increasing frailty limited his attendances. He was a regular speaker at club lunches, where his skill as a raconteur and his laconic timing always ensured a full house. At one such occasion he surveyed his audience and announced that he was fascinated by the rubric on many of his supermarket purchases which read "Best Before". This, he said, was of no interest to him. What he really wanted was, "Fatal After".

Many of his anecdotes related to his war service which, although one would not know it from the hilarious character studies of his companions, had been traumatic. Of six close friends who had graduated from Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, in 1939, he was the only one who had survived the war. While on mine-clearing duty in North Africa in 1943 he was blown up by a mine which shattered his right arm. After 18 months in and out of hospital he became an instructor, "showing chaps how not to lift a mine." After the war he completed his architectural studies and went on to study in Zurich before returning to London. There he shared a house with six architects and painters, which was so disorganised and cluttered that, he said, "a large bicycle was once lost in a room for six weeks."

Apart from the Leeds Club, he was associated with much Leeds development, being involved with the Henry Moore Sculpture Trust (after the City Council had wined and dined the locally trained sculptor and persuaded him to fund a new gallery), the Leeds Civic Trust and the Yorkshire Heraldry Society.

Michael Meadowcroft

Denis Mason Jones, architect and artist: born Linton, West Yorkshire 19 March 1918; married (two sons, two daughters); died Leeds 8 January 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments