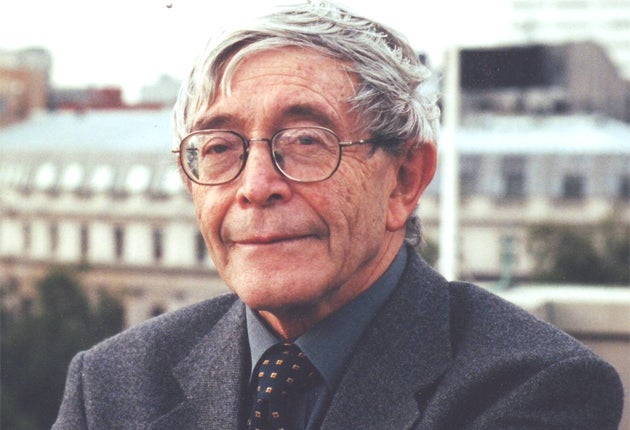

David Soggot: Lawyer who fought for justice in apartheid-era Namibia

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.David Soggot's induction into the political life of the colony of South West Africa (now Namibia) was brutal and bloody. It was 1973, and the Anglican suffragan bishop in Windhoek, Richard Wood, unable to find a local lawyer to act on behalf of Swapo nationalists being flogged by South Africa's black quislings, had telephoned the human rights advocate in Johannesburg."I'll be on the next plane," was the response.

"Time was short," the bishop's wife, Cathy, recalled. "It all happened over a weekend. The victims came down the 300 miles from Ovamboland to our house, the Manse. They couldn't sit down. It was too painful. David took the statements in the living room while I typed them up." Church elders, schoolteachers and businessmen, men and women, told how they had been sjambokked in public, some of them 50 times, on their naked bottoms.

Soggot won a two-week injunction to halt the floggings. When he returned to the Windhoek court seeking a permanent ban he found that the judge had been transferred back to South Africa. The new bench of local men refused to renew the injunction, even refusing Soggot leave to appeal to the Appellate Division in South Africa. Though the movement was not outlawed, ordinary Swapo members faced further mediaeval punishment. Soggot persisted, and in time South Africa's chief justice ordered a permanent ban on arbitrary flogging.

David Henry Soggot was born in Johannesburg to Lithuanian Jewish immigrants. His father was a butcher while his mother brought up David and three older siblings. From Parktown Boys School, he studied law at the University of the Witwatersrand, where he was active in the Progressive Forum, affiliated to the Trotskyist Unity Movement.

He was not in harmony with the Communist party, where many white radicals found a home. His political contribution was in the courts. Over the years he advised the likes of Winnie Mandela; Terror Lekota, who later would launch the Congress of the People party; and Steve Biko, father figure of Black Consciousness and the country's most influential black politician.

In a lengthy show trial, nine leaders of the Black Consciousness Movement were charged in 1975 under the Treason Act, though it was their ideas rather than their deeds at stake. Biko was not charged and became a defence witness. As he was restricted to Eastern Cape, Soggot obtained permission for him to live in his home during the trial.

The lawyer's meticulous examination and his admiration for the charismatic leader offered Biko the chance to lay out as never before his political philosophy. Inevitably, all the defendants were convicted and sent to Robben Island prison. Biko was punished as well. In 1977, the police killed him.

Meanwhile Soggot had been briefed to defend a group of Namibians charged with murdering Chief Elifas, the Ovambo leader responsible for the floggings. Soggot wasn't able to appear in the trial but later defended Victor Nkandi, charged with driving the assassins to the bar where Elifas was killed. His tireless cross-examination revealed violent police interrogation practices, with prisoners suspended upside down from iron bars and electrodes clamped to testicles and women's breasts, conducted in a sinister waarheidskamer (truth room).

The case collapsed, the judge blaming "unreliable black witnesses", not the police. "There was not a single police witness," he said, "who did not make a favourable impression upon the court." The judge president was so annoyed with defence counsel that he threatened a contempt of court charge because the counsel's well-used robe was torn.

Justin Ellis, a Namibian friend, said of Soggot that he "understood that the courts could be used to create a very public drama, different from other media, showing something of what was going on in the country. Previously we had not had lawyers in Namibia who were willing, and fully able, to take on the South African government in this way. It was a real and courageous contribution to bringing that crazy and violent era to an end, and limiting the violence of the heritage."

There were other trials. Millions had seen television shots of young men "necklacing", hanging burning tyres around the necks of, a suspected scab. The death penalty seemed certain but Soggot found an American social psychologist who introduced the phenomenon of "de-individuation" to explain the frenzied behaviour of the accused. They were convicted, but with mitigating circumstances and so avoided the gallows.

His activities did not please the security police. There were menacing phone calls, his car tyres were shredded, and after he had exposed serious assaults on Robben Island prisoners in 1977 the Minister of Justice attempted, unsuccessfully, to ban him from contact with political prisoners. Not surprisingly, he was not made a judge in the apartheid years, nor would he have accepted the offer. After the Mandela thaw, he sat several times as an acting judge. Earlier in his career he had lectured in political science at his old university.

But life was by no means all blood and courts. When time allowed, he enjoyed flying his Piper Cub. A bon viveur, he spent a large part of the year in London with his second wife Greta, or in France, where he learned to speak the language as well as he did English and Afrikaans. In his final years, ill-health prevented him from indulging most of his passions but he found solace in painting.

David Henry Soggot, lawyer: born Johannesburg 7 August 1931; married firstly (two daughters), secondly (one son, one daughter); died Johannesburg 24 May 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments