David Shepherd: Artist and conservationist sneered at by critics but whose work sold in droves

His great passions included steam trains and African wildlife, and he did much to preserve both of them

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.David Shepherd was the first to admit he had no natural talent. When he submitted his first oil painting, Seagulls, to the Slade School of Art in London, his application was promptly rejected. In its reply, the school described the work as a depiction “of birds of dubious ancestry, flying in anatomically impossible positions over a lavatorial green sea”.

“I couldn’t have put it better myself!” Shepherd later acknowledged.

That early setback, contrasted with his later popularity as a prolific painter of nature and industry, gave him the conviction that any person with enough determination could be taught to paint. Though shunned by critics, his wildlife art became immensely popular, and gave him a platform from which to advocate for wildlife preservation in Africa and beyond.

Born in 1931 in north London, David Shepherd was a rather nervous boy who led, in his own words, “the usual sheltered middle-class life”. The Second World War, which he found to be “madly exciting”, gave him licence for some adventure, however, as he and his brother would learn to recognise the planes flying overhead, and collected unexploded shells and other military relics in the aftermath of bombings.

His father worked in advertising before the war, and in hotel management after it. The family as a whole was not especially artistic, and the young Shepherd had no particular interest in painting either, although he did join the school’s art club in order to avoid being roughed up at rugby. Inspired by the books he read as a child, which told the stories of pioneers who “opened up Africa”, he dreamed of becoming a game warden.

His father did not object, and even paid for his travel to Kenya. On arrival, in 1949, Shepherd soon realised he was “a very square peg in a very round hole a long way from home”. The warden of the Nairobi National Park rejected his application as a matter of course – after all, he had neither much knowledge, nor experience, of Kenyan wildlife – and within a few months a dejected Shepherd was headed back to England. There he deliberated between what he thought were his two only options: earn a living as a bus driver, or starve as an artist.

He gave the second option a try by applying to the Slade – and the strongly worded rejection suggested that buses might in fact be his sole recourse. But a chance encounter with the marine painter Robin Goodwin at a party gave him the opportunity to receive the training he so desperately needed. On seeing Seagulls, Shepherd’s ill-fated painting, Goodwin said: “Oh my God, anybody who paints as badly as that I’ve just got to teach.”

Goodwin knew how to drive his student without quite breaking him, teaching him to paint every day from dawn till dusk. “Don’t talk all that rubbish about painting from your ‘innermost self’,” Goodwin said early on. To him, painting should be considered a business, and only through hard work could one earn a living from it. By 1953 Goodwin had taught Shepherd everything he could. “You’re on your own,” he said.

Heavy machinery fascinated Shepherd, and so he started his career at Heathrow airport. He would set up his easel on the tarmac and paint the planes, for sale to airline companies, among other clients.

In 1960, he was invited by the Royal Air Force to paint for the services in Aden, the port city in modern Yemen. He received an at-first cold welcome from the soldiers there but, having showed them how he depicted daily life in the bustling city, he was soon overwhelmed with commissions. This is when he painted, on a request from the RAF, his first wildlife scene as a professional artist: a rhinoceros chasing a Twin Pioneer off a landing strip. It is also when he became a conservationist: seeing 255 dead zebra at a poisoned waterhole convinced him to do something to protect wildlife from “the barbarity and cruelty of man”.

The Daily Telegraph called Shepherd “a peacetime war artist” upon his return from Aden. Soon he began to focus on wildlife, and found that, contrary to what gallerists thought, and perhaps as a result of lingering colonial feelings, such art was in high demand.

Some of his paintings were sold as mass-produced prints. One in particular, Wise Old Elephant, which was available at Boots the chemists, sold a quarter of a million copies. To many, Shepherd became “the chap who painted that elephant in Boots” – to his great despair. The print hung on the wall of Del Boy’s flat on the set of sitcom Only Fools and Horses, adding to Shepherd’s embarrassment. “Oh God, don’t point the camera at my painting, please,” he would say, “because people think I’ve never done anything else.”

Another painting of his, a depiction of the English countryside titled March Sunlight, also became a print bestseller. A journalist interpreted the painting as an evocation of sexual awakening – a reading which Shepherd called “nonsense”. To him, art was strictly figurative.

Shepherd might have made large sums of money from the print market but soon left it, deciding he would focus on limited editions instead.

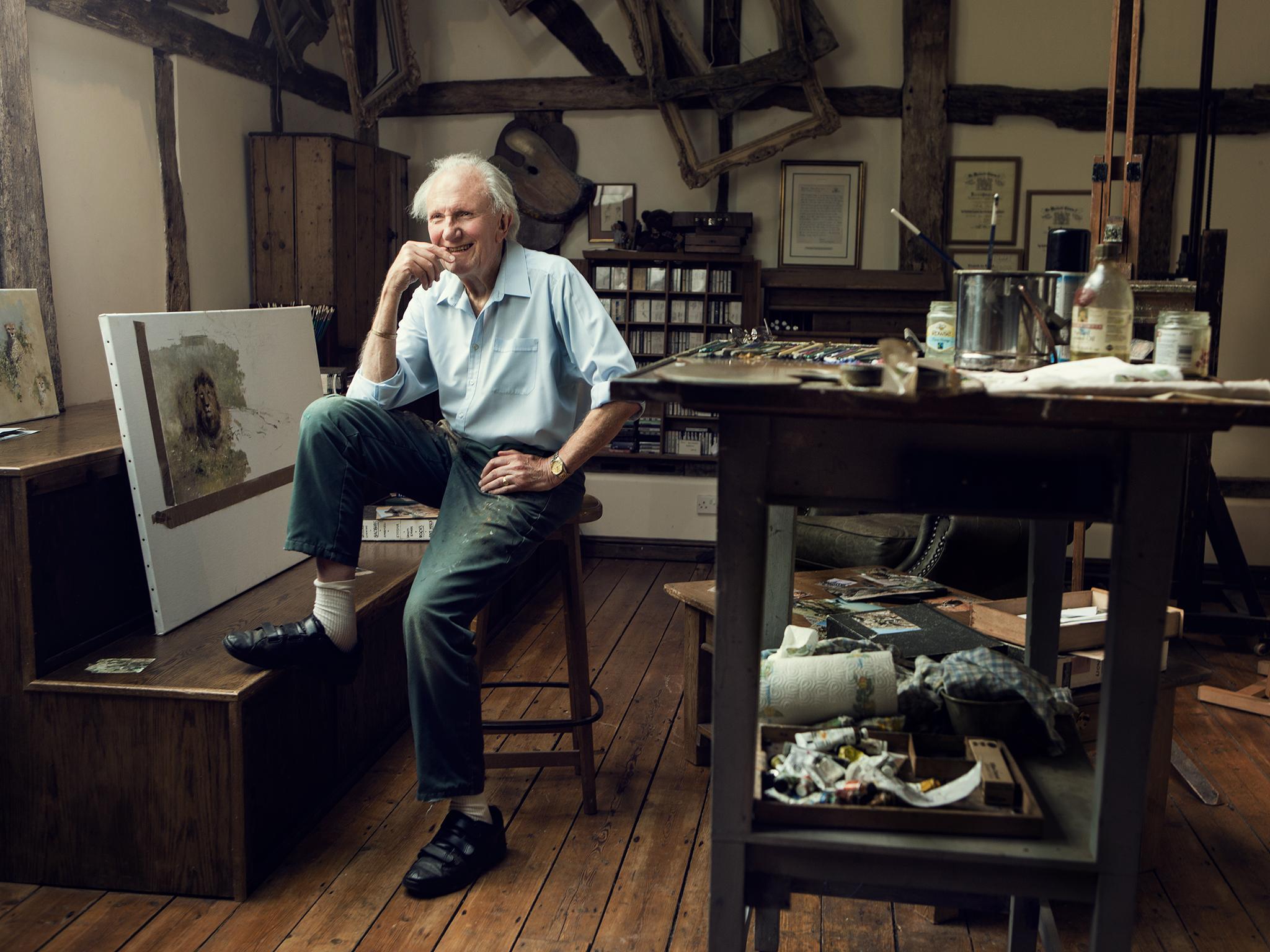

As well as African wildlife, which he would paint either on location or based on photographs from the comfort of his Elizabethan farmhouse in Surrey, Shepherd continued to paint heavy machinery. He was particularly passionate about steam locomotives, which were his favourite subject. Those works were so dear to him that he never sold them.

Feeling that he had to save something, somehow, of the vanishing age of steam, he started buying steam engines – two of which he acquired in Zambia – and recreated the East Somerset Railway as a heritage railway. Shepherd also set out to contribute to the preservation of wildlife, at first by collaborating with the World Wildlife Fund and later by founding the David Shepherd Conservation Foundation, which advocated for the defence of endangered species and fundraised millions of pounds, in part through the sale of his paintings, for that goal.

Shepherd’s at once theatrical and highly figurative style was panned by critics as “kitsch” and “really naff”. Shepherd held their opinions in contempt. Still, his obsession with getting every detail right did cause him personal trouble on occasion. The first portrait he ever produced of his wife Avril – who survives him, along with their four daughters – ended up in a cupboard under the stairs because he had made her pose for him when she had the mumps. “I painted her entirely from life and it is exactly like her, mumps and all!” he late wrote, unapologetically.

Shepherd remained faithful to Goodwin’s lesson that a painter should paint relentlessly every day. Listening to classical music or jazz, he would spend hours in his studio, producing, over decades, thousands of works of art. A creature of habit, he used the same two plywood palettes, which he made himself, and wore the same three pairs of paint-encrusted trousers, on which he would wipe his brushes, throughout his painting life.

That conservative streak, he readily admitted, was an essential part of his outlook on the world. “I live in the past in many ways,” he wrote, “and am desperately saddened to see how life has changed for the worse… I have so many chips on my shoulder I can hardly walk.”

In much of his art – be it depictions of steam engines or African wildlife – Shepherd grasped at a past whose chances of survival, he contended, were bleak. Hollywood actor James Stewart, who was a fan of his paintings, seized on that sentiment in his foreword to Shepherd’s memoirs, The Man who Loves Giants, finding some solace in it nonetheless: “It’s a comfort to me to know that my great-grandchildren, in their world which may not see either elephants or steam locomotives, will still be able to look at a David Shepherd painting and say ‘great’.”

David Shepherd, painter and conservationist, born 25 April 1931, died 19 September 2017

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments