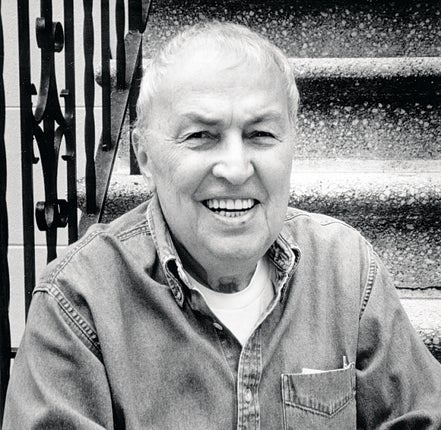

David Markson: Idiosyncratic novelist whose books eschewed literary convention

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."Rilke never read a daily newspaper." This is but one of the many one- or two-sentence paragraphs comprising David Markson's novel Reader's Block (1996).

It nominally tells of a stricken writer's retreat to finish a book: that's the plot, but, typically Markson, the book is an astonishing compound of observations and outré fact, such as John Berryman's remark, "Rilke was a jerk" – and a reminder that Berryman's original surname was Smith.

This method, much admired by David Foster Wallace and Zadie Smith, sprang from a series of huge, diversely brilliant letters which Markson had received a couple of decades earlier from Malcolm Lowry shortly before that novelist's death in 1957. At that time, aged 30, Markson was yet to find his way as a writer. Born in Albany, New York in 1927, he spent two years in the Army before a Union College degree led to journalism and an MA (later a book) at Columbia on Lowry's recent Under the Volcano.

Markson took up logging in Oregon before returning to Greenwich Village in its classic era. Acquaintance with Dylan Thomas and Kerouac did not hamper work at Dell and Lion paperbacks. After marrying Elaine Kretchmer in 1956, Markson published his first novels – crime novels which evoke the Village: Epitaph for a Tramp (1959) and Epitaph for a Dead Beat (1961). Back in Manhattan, he published Miss Doll, Go Home (1965) and turned his Western preoccupations into The Ballad of Dingus Magee (1966), whose film rights netted $75,000.

He wrote Going Down (1970), Springer's Progress (1977) and Wittgenstein's Mistress and then left Elaine for the painter Jean Semmel. Reader's Block followed in 1996, This is Not a Novel (2001), Vanishing Point (2004) and, finally, The Last Novel (2007).

David Markson, novelist: born New York 20 December 1927; married 1956 Elaine Kretchmer (two children); died New York 4 June 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments