David Koch: Billionaire industrialist who influenced US conservative politics

With his brother Charles he poured money into Republican and libertarian causes, and he was also one of the most generous philanthropists of his era

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.David Koch was a billionaire industrialist and philanthropist whose fortune and hard-edge libertarianism had a profound effect on American politics while making him an uncommonly polarising figure.

Koch, who has died aged 79, had suffered from prostate cancer for many years and announced in 2018 that he was stepping down from his positions at Koch Industries and the Koch political and philanthropic networks.

Koch and an older brother, Charles, transformed the Wichita-based family company, which they had taken over from their father Fred in the 1960s, into a global conglomerate with interests in businesses from petroleum to ranching to a wide variety of consumer products, such as Dixie cups and Stainmaster carpeting.

Koch Industries became the second-largest privately held company in the US, and by 2018, Charles and David Koch were estimated to be worth about $60bn each.

As a patron of charities, David Koch ranked among the most generous donors of his era, disbursing more than $1bn to cultural and medical nonprofit organisations. But it was through a network of well-financed advocacy groups that the Koch brothers achieved their greatest distinction, spreading an uncompromising anti-government gospel that moved the Republican Party steadily to the right.

They inherited a deep mistrust of big government from their father, a founding member of the arch-conservative John Birch Society. David Koch said he fervently believed that minimal government led to more prosperity and freedom for all people.

In 1980 David Koch was the Libertarian Party’s nominee for vice president on a ticket with corporate lawyer Ed Clark. He aligned himself with a platform that called for the abolition of all corporate and personal income taxes, Medicare and child labour laws. When the ticket flopped at the ballot box, gaining 1 per cent of the popular vote, the brothers pinned their political ambitions on the ascendant Reagan-era Republicans.

The Kochs’ chief instruments were Americans for Prosperity, a nonprofit group founded in 2004 and technically dedicated to “social welfare”, and semi-annual conclaves that attracted some of the wealthiest conservative donors in the country. In the 2016 election cycle, the Koch network spent nearly $900m, not much less than the total laid out by the Republican Party.

Over time, evidence of the Kochs’ influence could be found in almost every corner of the political landscape. On the state and local levels, Koch money was credited with helping Republicans to gain majorities in 31 state legislatures by 2018.

The Koch brothers also poured money into think tanks and other groups that promoted their agenda, including the denial of climate-change science. Greenpeace, which dubbed Koch Industries the “kingpin of climate science denial”, once ranked the company above ExxonMobil in working to scuttle legislation meant to reduce or reverse climate change.

On some issues, including same-sex marriage and legalised abortion, both of which he supported, Koch hewed to his libertarian outlook and departed from traditional Republican orthodoxy.

When it came to businessman and reality TV star Donald Trump, who derided candidates who sought Koch money as “puppets”, the brothers made little secret of their distaste and refrained from supporting his presidential campaign in 2016.

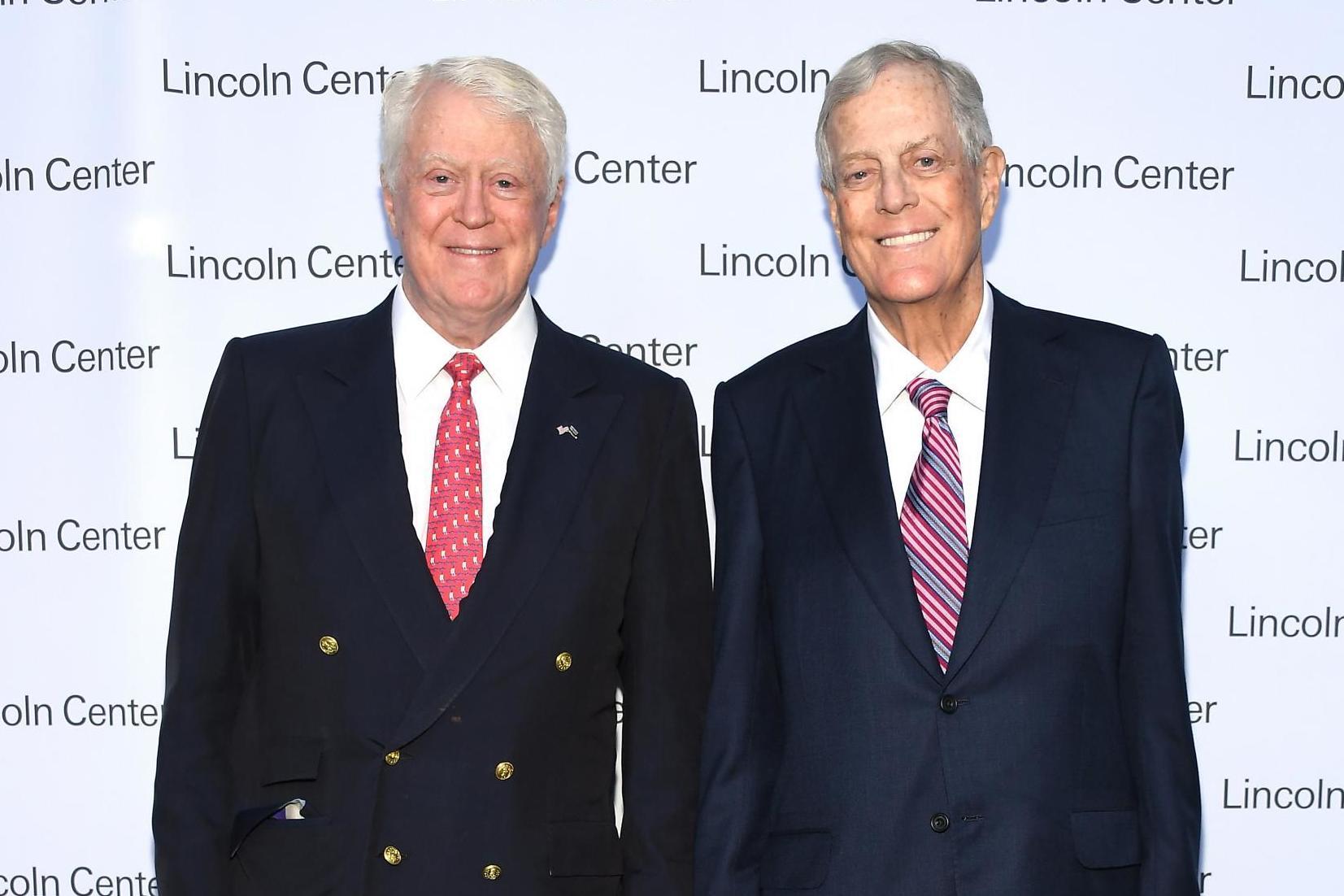

For many people, the affable and outgoing David Koch was the public face of the brothers’ political activity. At the same time, it was generally understood that Charles Koch, who served as the head of Koch Industries, was the driving force behind the scenes.

The exact total the brothers gave to political causes is not known, because much of it was “dark money” routed through nonprofit groups that were not required to disclose the sources of their funding. But estimates of those contributions range into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

David Hamilton Koch was born in Wichita in 1940. His mother, Mary Robinson, was a well-known figure in Wichita society, and his father was a chemical engineer and entrepreneur who prospered in oil refining. His father was a strict disciplinarian who insisted that his four sons – Frederick, Charles and twins David and William – perform manual labour to foster a strong work ethic.

David Koch graduated in 1958 from Deerfield Academy, a prep school in Massachusetts, and then entered the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, his father’s alma mater, which was also attended by his brothers Charles and William.

He studied chemical engineering, receiving a bachelor’s degree in 1962 and a master’s degree in 1963. As an undergraduate, Koch, at 6ft 5in, was a standout on the basketball team, setting the university’s single-game scoring record. After graduation, he worked for a series of consulting firms before joining the family company in 1970. He inherited $300m in 1967 after his father’s death.

Over the years, Koch Industries was plagued by bitter sibling rivalries, with David and Charles Koch pitted against Frederick and William. In 1980 the latter two led an attempted takeover. The gambit failed and led to years of acrimonious litigation.

In contrast to Charles, who enjoyed a staid family life in Wichita, the headquarters city of Koch Industries, David Koch chose to live for years in New York. He relished his life as a freewheeling bachelor and frequent party host until what he described as a life-altering event in 1991: his escape from an aeroplane disaster at Los Angeles international airport.

He was aboard a commercial airliner that collided with a commuter aircraft on the runway. Koch’s plane swerved into a building and caught fire. With smoke filling the cabin, he managed to force open a door and exit to safety. Thirty-three people died in the accident, and Koch suffered serious burns to his lungs.

“This may sound odd, but I felt this experience was very spiritual,” he told New York magazine. “That I was saved when all those others died, I felt that the good lord spared my life for a purpose. And since then, I’ve been busy doing all the good works I can think of.”

After the accident, Koch embarked on a wide-ranging campaign of philanthropic giving. Among the many beneficiaries of his largesse were various cancer research institutions, which received hundreds of millions of dollars, the American Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian Institution.

In 2008 he donated $100m for the renovation of New York State Theatre at the Lincoln Centre, the home of the New York City Ballet and New York City Opera. In all, Koch was estimated to have doled out at least $1.3bn to scientific research and nonprofit arts groups.

He is survived by his wife Julia and three children.

David Koch, industrialist, born 3 May 1940, died 23 August 2019

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments