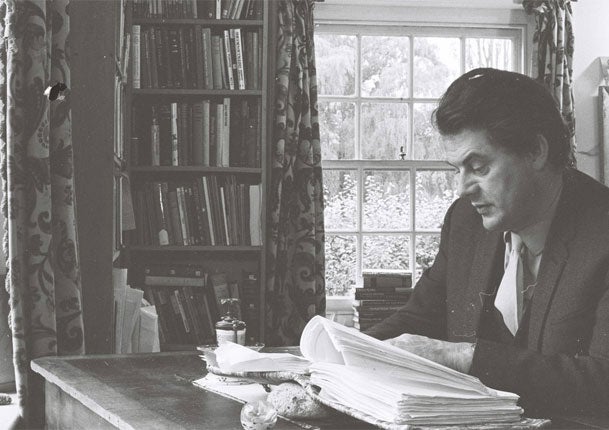

David Holbrook: Writer and inspirational teacher who worked towards his vision of a national culture open to the entire nation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.David Holbrook was one of a remarkable quartet of socialist-minded officer conscripts who returned from the Second World War fired with the ambition and gifted with the talent to give their particular corner of the nation's education moral and egalitarian purpose, to recover the people's culture for the people, above all to make the splendours of a national literature the property of the whole nation.

At the same time, these men – Holbrook, Raymond Williams, Richard Hoggart and EP Thompson – dedicated themselves to writing and to making, by way of critical commentary, novels, poems, journalism, autobiography, their own, bold contributions to the new culture demanded by a new world order brought into being by the anti-Fascist victory, and for which they spoke as writers, teachers, citizens. Holbrook proved the most prodigiously productive of the four.

He was born in Norwich in 1923, his father a railway clerk, and won a scholarship to the City of Norwich School, spending his leisure time at the Maddermarket Theatre where he was much influenced by the loving genius of its director, Nugent Monck, a story Holbrook vividly tells in one of his novels, A Play of Passion (1978). He won an exhibition to Downing College Cambridge in 1941, but was instantly called up to serve in a Yeomanry tank regiment, eventually floating ashore on D-Day in a Sherman with inflatable sides, slowly and strenuously paddling on to the beach-head like a vast armadillo. He was wounded, shipped home, went back to the Battle of the Bulge and turned the epic of liberating destructiveness into perhaps his best novel, Flesh Wounds (1966).

When he returned to Cambridgein 1945 he had the excellent goodfortune to be taught English literature by the irresistible FR Leavis, thenat his scathing and generous best, and learned that the whole duty of manat this juncture of history was to live the life of poet, novelist, teacher, lover, father, gardener, journalist, carpenter, painter, and live it according tothe preachings of his great Romantic forebears, DH Lawrence supreme among them, as completely aspossible. No one can doubt that he brought off this colossal adventure as a mighty triumph.

He went to teach secondary modern schoolchildren at one of the new village colleges, Bassingbourn, the imaginative product of the great Henry Morris. There he taught the books, music, old rhymes and songs, games (Holbrook later wrote a little classic, Children's Games, the very title of which tests the depth of the abysms of our cultural losses), the folk tales, the habits of speech and dialect, which would replenish their spirits and fill up the old carpet bag of culture.

Out of this tense, fulfilling, high-pitched experience (Holbrook could do nothing sotto voce) came his classic book, English for Maturity (1961). Rousingly polemical, written for teachers who duly bought it in their thousands, it spoke a curse over the deathly emptiness of commercial culture, and showed in vivid detail how and what to teach in order to make English the subject at the heart of what matters in learning, how the best use of one's language, whether by a great poet or the child in the back row, is a rediscovery of civilisation, of the creative life which connects us one to another and makes a decent future out of a cherished and criticised past.

In 1964 he went, by way of the good offices of Royston Lambert, to a four-year fellowship at King's, Cambridge and there published The Secret Places, an astonishing application of DW Winnicott's psychoanalysis to the writings of barely literate children obdurately hostile to school but turned by the magic of Holbrook's teaching and interpretation into makers of selves and poets of their day.

Accompanying this venture came Holbrook's single-handed recastingof the whole subject curriculum, avolley of anthologies: poetry in Iron Honey Gold (three volumes) and short stories (People and Diamonds) which brought writers unknown in classrooms – Isaac Rosenberg, Edward Thomas, George Herbert, Edgell Rickword among the poets, Lawrence, TF Powys, Hemingway among the story-writers – withwhich to enrich or supplant the the Grammar School library. Integral to his pedagogy were his own poems, resolutely traditional in theme – love, marriage, children, sex and its redemptions – while modern in idiom and movement; Object Relations (1967) and Chance of a Lifetime (1978) were perhaps the best collections.

He then set himself – solitary in all his work after the great rush of school books – the giant task of contriving a psychoanalytic existentialism with which to oppose the worst that consumer capitalism could do to people. Parts of this venture nowadays sound perhaps a bit barmy, great lumps of exposition thrown arbitrarily together. For all that the meaning of meaning was his great topic, he too often allowed himself a damaging looseness in his terminology. But when he turned his passionate affirmation upon his enemies – as in The Masks of Hate, in which he examined the James Bond novels and found them passionlessly brutal and Fleming himself indifferent to sexual exploitation, with a keen relish of cruelty – then dissent begins to look pretty compromised. In Sex and Dehumanisation he proved the first writer of such standing to name and instantiate the horrible and premature deformations of sexuality now a commonplace on the Dave channel or such repellent manifestations of customer choice as Californication.

He wrote and wrote unstoppably, 49 books in all. The last, English in a University Education in 2006 is an irrefutable lament sung over the terrible hiatus which has opened up between the comfort and replenishment of civilisation stored in a great body of literature, and the moral emptiness of so much university study in the humanities, which fails to provide, as Holbrook rightly believed it should, ideals to live for and principles to live by.

He lost the tremendous scale of his influence over the last three decades in education, dominated as they have been by the dreadful jargon of managerialism, although he never stopped teaching. But all great figures do that, in time. He retained his stirring powers of affirmation (for instance in his late, gallant study Gustav Mahler and the Courage to Be), and he did so much; he lived his life and his work as a unity; he embodied the best domestic and private virtues and stood up for them in full public and dramatic view, the result being itself a strong work of art and a pressing example to later generations.

David Kenneth Holbrook, writer: born 9 January 1923; married 1949 Margot Davies-Jones (two sons, two daughters); died 11 August 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments