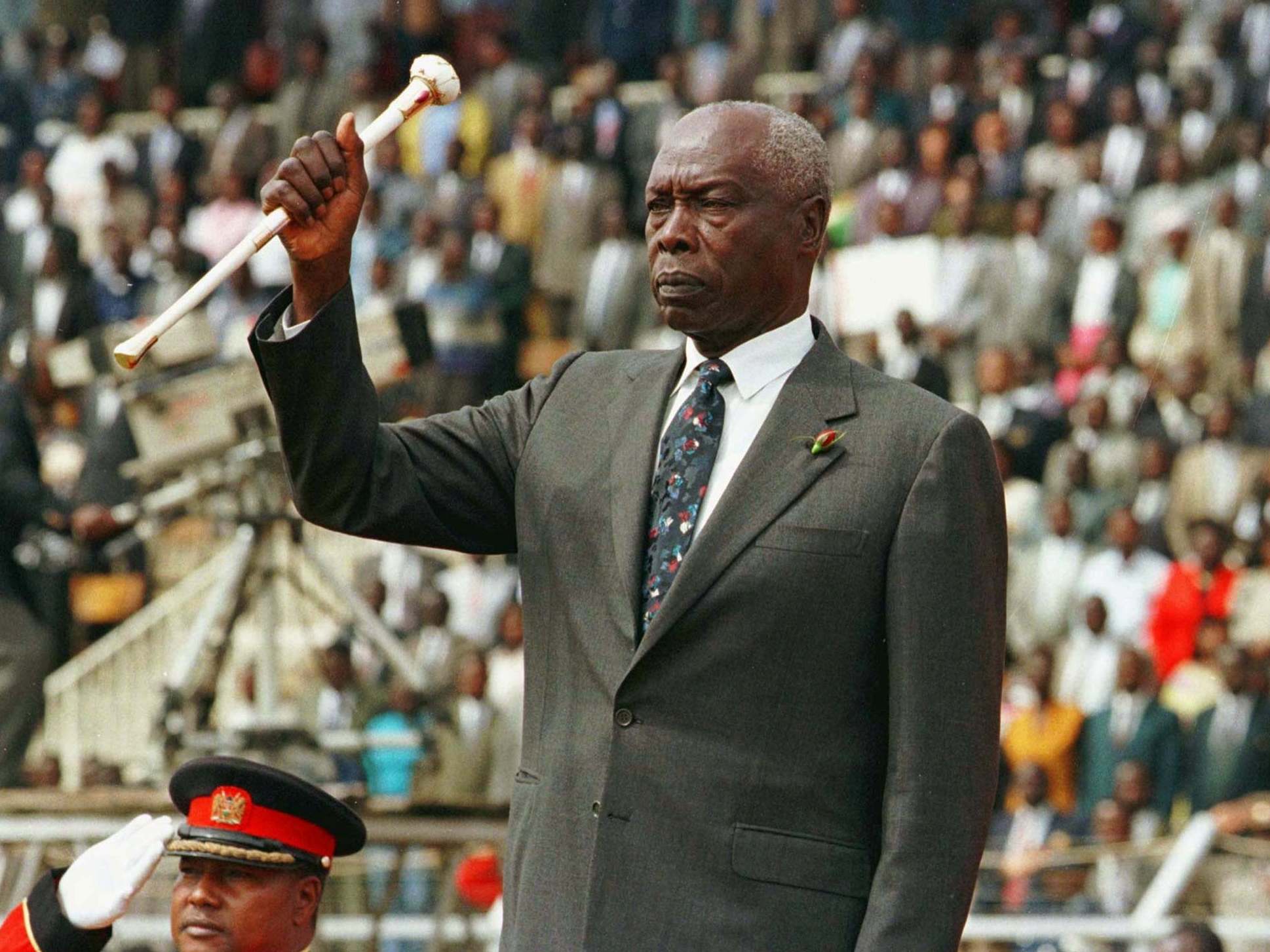

Daniel arap Moi: Kenya’s longest-serving president who oversaw political and economic decline

He led the African nation for 24 years until 2002, an era marked by corruption and authoritarianism

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Daniel arap Moi, the former president of Kenya who has died aged 95, never commanded the respect and popularity of his predecessor Jomo Kenyatta, the nation’s first president and leader of the independence movement. But he was a master of political manipulation, a born survivor who stopped at little in order to maintain power for 24 years, from 1978 to 2002. Nor was he averse to using his power to amass a large personal fortune.

Moi never had a grand political vision for Kenya, but rather advocated laissez-faire social and economic policies, bore a large measure of responsibility for the nation’s gradual decline during his years in office. He inherited one of Africa’s more successful and stable post-independence nations, but bequeathed one saddled with a degraded political culture and rent by tribal divisions, a nation in which an impoverished majority suffered one of the highest crime rates in the world while a small and corrupt elite pursued the perpetuation of their predominance by any means.

He was born in 1924 in the Baringo district of the Rift Valley Province in western Kenya. Educated in mission schools, Moi first embarked on a career as a teacher and headmaster. The first steps in his political career were along the path approved for Africans by the British colonial authorities. In 1955 he was selected as the Rift Valley’s African representative to the Kenya Legislative Council.

In this role Moi rose to prominence in the negotiations that led to independence, making himself useful both to the nationalist movement and to the British. As a member of the small and loosely knit Kalenjin tribal group, he was able to present himself to the British as a counterweight to the powerful Kikuyu tribe, which dominated the nationalist movement. To the nationalist leadership he appeared neutral in the factional and clan infighting to which the Kikuyu were prone.

Moi served in various ministerial roles in the pre-independence coalition governments and took part in the British-sponsored conferences which hammered out the details of the transition to independence. When independence came in 1964, he was given the home affairs brief, which gave him control of the police and responsibility for national security. Here he made himself indispensable, taking the brunt of any criticism levelled at his boss Kenyatta, who was was still in prison, having been tried on charges of directing the Mau Mau rebellion.

He was appointed vice president in 1967 and, upon Kenyatta’s death, in 1978, assumed the presidency with little overt opposition, a fact he owed to a number of factors. To the 80 per cent of Kenyans who were not Kikuyu, Moi represented a chance to curtail Kikuyu power and reinforce national unity through building a coalition of smaller tribal groups. This later proved to be a tragically illusory promise.

On coming to power Moi promised continuity, intending to be seen as following in the footsteps of Kenyatta both as a nation-builder and ally of west. He also launched a much-publicised campaign to stamp out corruption, but this soon proved to be merely cosmetic.

In 1982 Moi banned political parties except for the ruling Kenya African National Union (Kanu) party. Parliamentary debate was stifled, the press was muzzled and critics of the government’s policies found themselves the object of police harassment, in prison or under house arrest. After a coup attempt by officers in the air force in 1982, Moi purged the officer corps of the armed forces.

The west regarded Moi as a bastion of stability and a Cold War ally, and despite a less-than-satisfactory human rights record, he won plaudits from admirers like Margaret Thatcher and from successive US administrations, which enjoyed the use of military bases in Kenya.

The end of the Cold War, however, coincided with serious economic decline in Kenya as the country began to reap the bitter harvest of Moi’s economic and social policies, and of massive corruption. Western support from became conditional on political and economic reform and an improvement in the government’s human rights record.

Initially Moi resisted such pressure, but matters were brought to a head following the murder in 1990 of Robert Ouko, longstanding foreign minister. Nicholas Biwott, industry minister and Moi crony, was implicated: Biwott was dismissed but the crime was never solved, leading to suspicion that Moi ordered the assassination.

In 1991 aid donors announced a suspension of aid and Moi reluctantly agreed to allow the registration of political parties. But the 1992 elections were marked by efforts to discredit and divide the opposition. Serious tribal clashes which broke out in the west of the country were allegedly incited by Moi’s agents in an effort to vindicate his claim that multi-partyism would breed tribal conflict.

In 1993 and 1994 more ethnic clashes broke out in the Rift Valley leading to hundreds of deaths and the eviction of thousands of Kikuyu from their villages by people of Moi’s own Kalenjin tribe. Moi used the violence as an excuse to extend police powers and to arrest opposition leaders.

By the mid 1990s it was clear that Moi’s style of government was leading Kenya down a slippery path to disaster. There were even predictions that Kenya could go the way of its eastern neighbour Somalia, where Moi had deliberately fomented the civil war by providing military support to the faction of the ousted president, Siad Barre.

He won elections in 1992 and 1997. In the run-up to the latter, Moi recalled Biwott to his cabinet, opposition demonstrations were violently broken up, tribal conflict was fomented in the coastal regions where tens of thousands were forced to flee their homes. Only when donors again threatened to suspend aid did Moi agree to some cosmetic amendments to electoral rules, which stacked the odds heavily in his favour. He did not stand in the 2002 election, as per the requirement of the Kenyan constitution.

Moi’s lack of charisma and vision was compensated for by an aloof, almost regal style, his skill laying in knowing just how far he had to go towards political reform to satisfy his western allies and aid donors. In a country dominated by tribal politics, he was acutely aware of the vulnerability of his position as a member of a small and insignificant tribe. He made up for this vulnerability by cynically manipulating tribal politics in his own favour, whatever the cost to Kenya as a nation.

He is survived by eight children.

Daniel arap Moi, former president of Kenya, born 2 September 1924, died 4 February 2020

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments