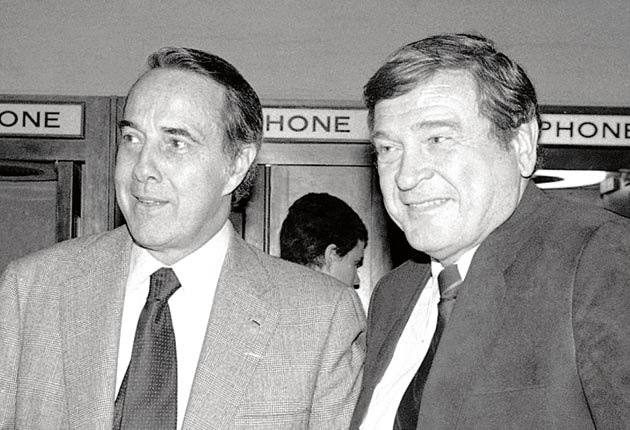

Dan Rostenkowski: Influential politician who served in the US House of Representative for 36 years but whose career ended in scandal

If you like your politics Chicago-style, then Dan Rostenkowski was your man.

He was a creature of the smoke-filled room, a master of the deal, of favour given and favours returned. He was big and lumbering, but like any self-respecting product of the Chicago Democratic machine he could count votes. Depending on mood and circumstance, he could be grave, genial, wheedling or bullying. And like not a few politicians from the Windy City, he ended up a convicted felon.

Washington's culture has changed drastically since Rostenkowski's heyday – and no event captured the change more than his indictment in 1994 on corruption charges. His downfall was a factor in the rout of the Democrats in that year's mid-term elections, heralding the era of 24/7 partisan warfare that persists to this day. But it cannot erase Rostenkowski's huge legislative achievements, that led a biographer to describe him as "one of the half-dozen most influential members of Congress in the second half of the 20th century."

His father Joseph, known as "Big Joe Rusty", was alderman for Chicago's 32nd ward, a post he passed on to young Danny. At high school the son was a star athlete who was offered a try-out by the Philadelphia Athletics baseball team. But "Big Joe" wanted his boy to be a politician, and so it would be. In 1952, Rostenkowski was elected to the Illinois state legislature at the tender age of 24, and in 1958 he won the seat in the US House of Representatives that he would hold for 36 years.

For roughly the first 15 of them he was the protégé of Richard Daley, Chicago's legendary mayor who decided everything in the city (not least who its voters would send to Washington). Every Friday "Rosty" would report in person to the "Boss" on what was happening in the capital. Over his career, Rostenkowski channelled vast sums of federal money to the Chicago area.

Soon though, he became a consequential figure in Washington in his own right. In 1961 he captured a coveted seat on the House's tax-writing Ways and Means committee, through which virtually all major legislation passed, and quickly earned a reputation as someone who could operate across party lines to get things done.

In 1965, Rostenkowski helped write the Medicare legislation that transformed American health care. In 1981 he became Ways and Means chairman. Even though Ronald Reagan was president, Rostenkowski forged common ground between the Democrat-controlled Congress and the Republican White House to secure two historic bills: the 1983 measure that saved Social Security from going broke and, three years later, the biggest overhaul of the US federal tax code since the Second World War, that eliminated countless loopholes and created a simpler and more equitable system.

It helped, of course, that Rostenkowski got on very well with Reagan and his successor George HW Bush; Chicago-trained politicians are nothing if not pragmatists who understand the realities of power. But in those days politics was an easier, more personal business. "We'd argue like hell on the floor of the House," he recalled later, "but by evening we were out playing golf."

Or they might ensconce themselves at Morton's Steakhouse in Georgetown, one of Rostenkowski's favourite hang-outs, washing down aged New York strip with martinis and Chateauneuf-du-Pape. "There would be steaks and lots of carousing," a colleague remembers, "and some lobbyist or group of lobbyists would pick up the bill." A spot near the bar even bore a plaque marked "Rosty's Rotunda". The city still crawls with lobbyists, but they are barred from buying such meals, and these days Washington mostly runs on bland mineral water and bitter partisanship.

All the while Rostenkowski re-mained fiercely attached to Chicago, still keeping a home close to Milwaukee Avenue in his district just west of downtown, a modest three-storey redbrick where he installed his mother and two sisters. But his loyalty to the city's ways would prove his biggest problem.

Essentially, he ran his Congressional office like the 32nd ward. He used his official expense account to finance perks, presents, even "ghost jobs" on his payroll – among them a Chicago Fire Department lieutenant paid for taking photographs at his daughter's wedding and a godson who mowed the lawn at Rostenkowski's summer home in Wisconsin. Some $50,000, prosecutors charged, came from converting his Congressional free-postage entitlement into cash.

Rostenkowski was indicted on 17 counts of fraud and other abuse. Just before his scheduled trial, he negotiated his final deal, pleading guilty to two charges of mail fraud. He served 15 months in prison and was fined $100,000. Far more important, he became an instant symbol of Congressional excess, of what can happen when people are in power too long.

In fact, many colleagues, Republicans as well as Democrats, thought he had been made a scapegoat. One was Gerald Ford, an old friend of Rostenkowski from his days as Republican minority leader in the House. "Danny's problem was he played precisely under the rules of the city of Chicago," Ford wrote. "These aren't the same rules that any other place in the country lives by, but in Chicago they were totally legal, and Danny got a screwing."

Ultimately, Rostenkowski was pardoned by President Bill Clinton just before he left office in 2001. But even his massive political accomplishments could not restore his reputation. "You walk into a room that you used to take command of," Rosty mused a few years before he died, "and then you get to thinking everybody's looking at you, and you're a crook. And that's sad."

Daniel David Rostenkowski, politician: born Chicago 2 January 1928; Member, US House of Representatives 1959-1995; Chairman, House Ways and Means Committee 1981-1994; married LaVerne Pirkins 1951 (three daughters, and one daughter deceased); died Genoa City, Wisconsin 11 August 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments