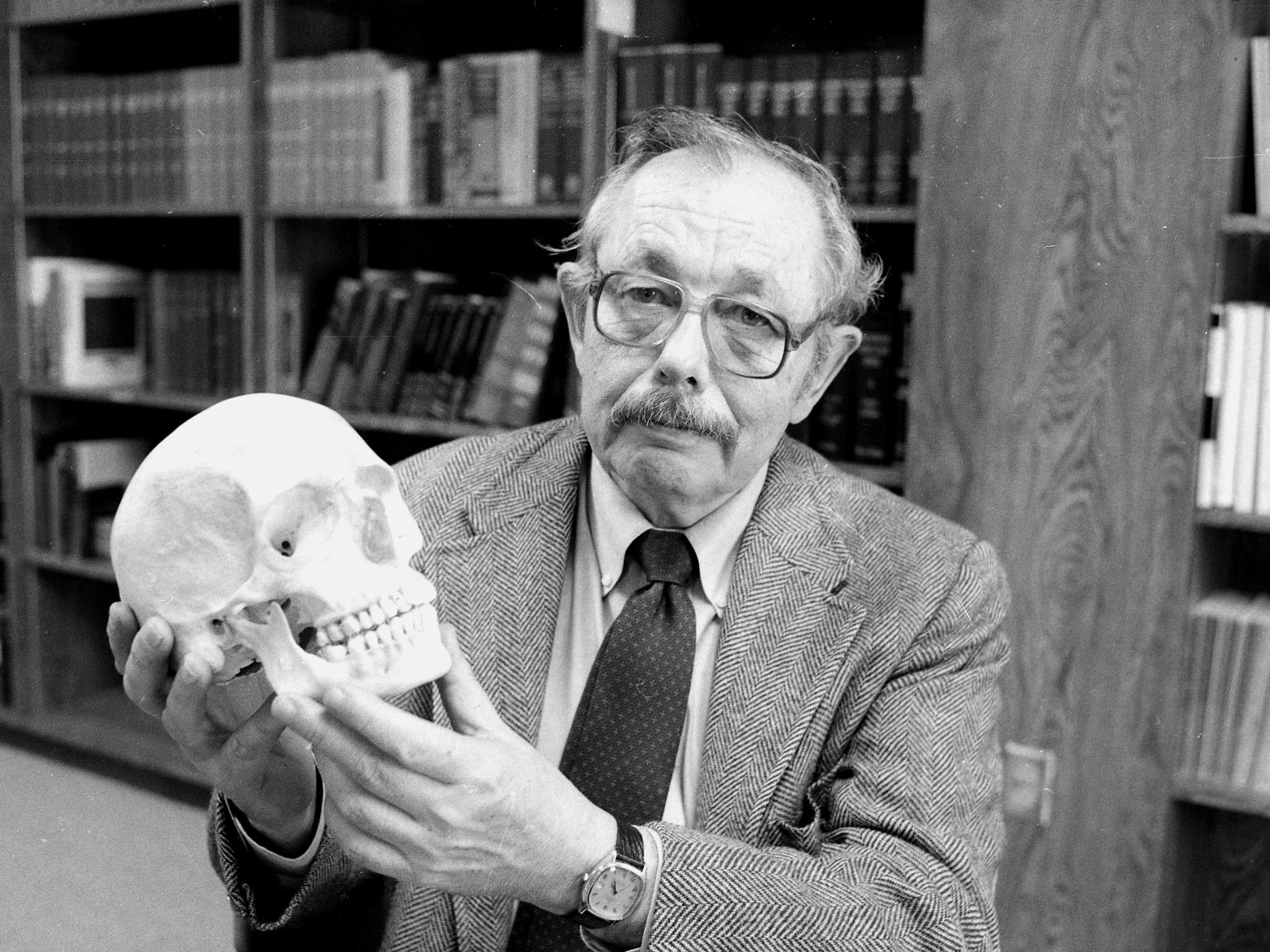

Clyde Snow: Forensic anthropologist whose pioneering methods helped bring the perpetrators of Argentina's dirty war to justice

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Clyde Snow was one of the US's foremost forensic anthropologists, who helped identify the Nazi war criminal Josef Mengele and countless victims of accidents, crimes and state-sanctioned abuses of human rights. He was a latter-day Sherlock Holmes, using keen observation, encyclopedic knowledge and a thorough understanding of human experience and the human skeleton to overcome the silence of the grave.

He solved many notorious crimes and historical mysteries. In addition to identifying the body of Mengele in South America, Snow helped to tell the story of Custer's Last Stand, confirmed the identity of X-rays taken after the assassination of President Kennedy; and refuted theories that Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were buried in a grave in Bolivia. "There are 206 bones and 32 teeth in the human body," he often said, "and each has a story to tell. Bones can be puzzles but they never lie, and they don't smell bad."

In 1985, as Snow's achievements became increasingly known, he was engaged by the Simon Wiesenthal Centre to identify remains found in a cemetery near Sao Paulo, Brazil. Snow and his examiners matched hair samples, noted a tell-tale curved left index finger, verified the dead man's hat size and determined that the fillings in his teeth were from Nazi-era German dentists.

The person who had lived for years in Brazil as Wolfgang Gerhard, Snow concluded, was Mengele, the notorious doctor who carried out gruesome medical experiments and killings in Nazi concentration camps.

In another mission, Snow was sent in 1985 by a scientific group to Argentina, where the military juntas' "dirty war" had caused as many as 30,000 people to be "disappeared." After leading a team that found and identified the bodies of many death-squad victims, Snow served as a witness at the trials of several high-ranking military officials accused of the killings. "If you can make people feel they're not going to get away with it," he said, "that's all we're asking."

Snow could glean names and stories not only from bones but also from the very ground under which executioners, in a variety of countries, tried to conceal their deadly acts. "The ground is like a beautiful woman," he said in Guatemala in 1991. "If you treat her gently, she'll tell you all her secrets." Those secrets included the deaths of tens of thousands of Mayan Indians liquidated in a bloody Guatemalan counterinsurgency programme in the 1980s.

In the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, Snow and his team determined that more than 200 victims found in a mass grave had been killed in an execution-style act of ethnic cleansing. He said he was driven by the pursuit of law, justice and human rights, as well as scientific curiosity. "His first passion in life," his wife said, "was human rights." In his 1991 interview, Snow said, "People will never respect the law until there's justice. And a good place to start is with murder ... It's very difficult to argue with a skull with a bullet in its head."

Snow grew up in the town of Ralls in the Texas panhandle. His father was a doctor, and his mother, although not formally trained, often served as his nurse. After being expelled from high school for pranks, Snow graduated from a military school in Roswell, New Mexico, then dropped out of several colleges before graduating in 1951 from Eastern New Mexico University.

After graduate work, which included a stint in medical school, he served as an US Air Force officer before enrolling in a doctoral programme in archaeology at the University of Arizona. He later switched to anthropology and received his doctorate in 1967.

Before receiving his doctorate, Snow had been enlisted by the Federal Aviation Administration to help find ways to enhance the safety of aeroplane passengers and he eventually headed the FAA's physical anthropology laboratory.

In 1979, Snow helped identify victims of a plane crash at O'Hare International Airport near Chicago. Of the 273 who died, 50 were unidentified when he began work. Snow and his team examined more than 12,000 body parts and used X-rays, photographs, computers and interviews with survivors to find such revealing signs as fractures, or indications of left-handedness that might help give names to the unidentified remains.

In 1995 he helped identify many of the victims of the bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City. And for a television programme in the early 1990s he had Snow travelled to South America in search of the remains of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. A grave where they were suspected of being buried in a remote Bolivian mountain village turned out to contain only the body of a German prospector.

Snow pioneered a number of techniques, including facial reconstruction. He helped reconstruct the face of Tutankhamun, but the practice also proved useful in solving crimes. Drawings based on recovered facial bones helped lead to the identification of some of the 33 victims of the mass murderer John Wayne Gacy in the 1970s.

Inspired in part by Snow's work, the American Academy of Forensic Sciences made a formal speciality of forensic anthropology.

After retiring from the FAA in 1979, Snow did consulting work in forensics and taught at the University of Oklahoma. A chain smoker who spoke in a slow Texas drawl, he was a witty man, not given to pretence. Once in Guatemala, he was asked about how he avoided troublesome confrontation with those who did not welcome his investigations. He responded by drawing from a pocket a large metal badge, carrying the words "Illinois Coroners Association." Members of the civil patrols in Guatemala , who might have caused him difficulty, carried only small badges, he said. "I always carry it around," He once said, "because whenever you get into a confrontation with police, the guy with the biggest badge wins."

MARTIN WEIL

Clyde Collins Snow, forensic anthropologist: born Fort Worth, Texas 7 January 1928; married four times (five children); died Norman, Oklahoma 16 May 2014.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments