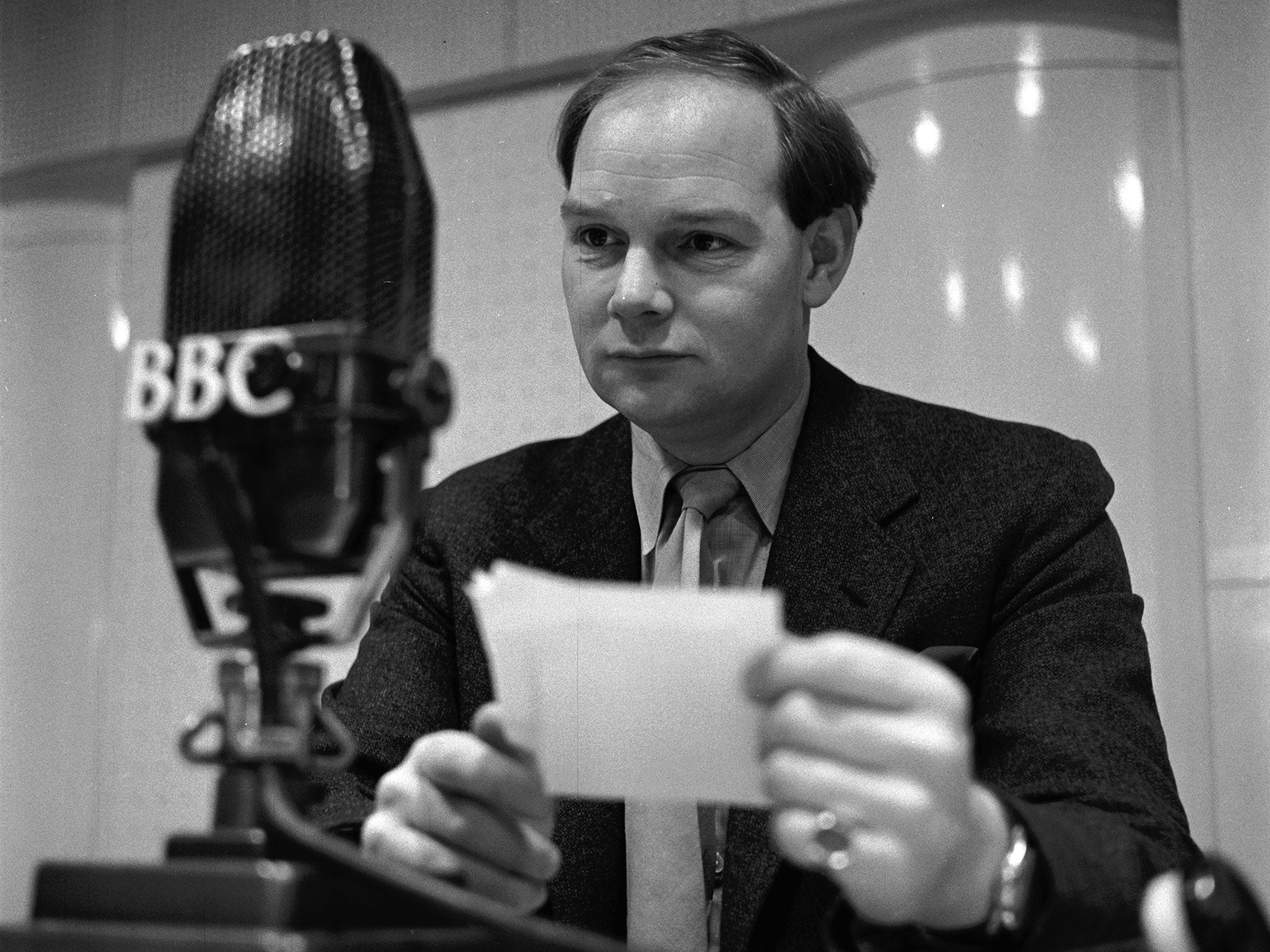

Cliff Michelmore: Broadcaster whose mixture of affability and seriousness helped transform television presenting

Michelmore's relaxed style struck an immediate chord with viewers and became the accepted tone of voice to be used in current affairs programmes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Cliff Michelmore's particular on-screen talent was well defined by Robin Day, a television presenter of a markedly different stamp. Writing in 1961, when Michelmore was at the height of his popularity as host of the BBC's early-evening Tonight programme, Day relished his "chummy have-another-pint-mate manner", while observing that it could quickly be replaced by a more serious approach when the varied subject matter demanded it.

Tonight was the most influential current affairs programme of television's early years, commanding at its peak a regular audience of around 10m. Its balanced mixture of light-hearted and more solemn items established a formula still followed by magazine programmes on many channels.

When Michelmore made his television debut in 1950, the prevailing presentational style was stiff and formal, with lines delivered in upper-class accents that, by today's standards, seem ludicrously affected. He changed all that. His relaxed affability, initially developed during his time as a radio disc jockey, struck an immediate chord with viewers and became the accepted tone of voice to be used in current affairs programmes.

Born in December 1919 at Cowes on the Isle of Wight, he was brought up by his mother from the age of two after his father died of tuberculosis. He attended the local school but left at 15 to join the RAF. Commissioned in 1940, he ended the war as a squadron leader, although his imperfect vision prevented him from flying and he was restricted to desk jobs.

When the war ended he was posted to Hamburg to look after the RAF's interests at the British Forces Network (BFN), the radio station established for the benefit of our troops occupying Germany. It turned out to be a serendipitous posting, his introduction to a lifetime of broadcasting. When he left the RAF he stayed on at BFN, becoming the deputy station director in 1949.

That was when his on-air career began. By far the most popular of BFN's programmes was the weekly Two-Way Family Favourites, in which servicemen chose records and exchanged messages with their families at home, who listened on the BBC Light Programme. When the regular presenter was taken ill, Michelmore stepped in and quickly achieved a rapport both with listeners and with Jean Metcalfe, his opposite number at the London end of the programme, whom he married in 1950.

Metcalfe was on the staff of the BBC and would soon become the highly regarded presenter of Woman's Hour. When the couple set up home in Reigate, Surrey, he found work as a freelance broadcaster for the Corporation. His Hamburg experience made him a natural choice to host Housewives' Choice, the daily morning request programme, and alongside this he developed a talent for sports commentary.

Unlike many of his contemporaries in radio, he was interested in exploring the possibilities of television, then in its infancy. Soon he gained a foothold as a producer of children's programming, about to be expanded from half an hour a day to an hour. His first on-screen appearance was in July 1950, in an outside broadcast from Wimbledon, when he explained the rules of tennis for the benefit of young viewers.

He was then appointed producer of All Your Own, a programme in which children demonstrated their hobbies. (Its presenter was Huw Wheldon, who, in the late 1960s would become managing director of BBC Television.) And before the end of 1950 Michelmore won his first regular presenting spot as host of Telescope, a fortnightly children's programme. Soon afterwards he graduated to adult current affairs with frequent appearances on Westward Ho, a regional magazine based in Bristol.

His big career break came in 1955, when commercial television was launched in London. As part of its attempt to broaden programming to compete with the new rival, the BBC launched Highlight, an early-evening interview slot that lasted just 10 minutes. Its producers were Donald Baverstock and Alasdair Milne, two men destined to rise high in the BBC hierarchy. Michelmore was one of the three regular interviewers, alongside Macdonald Hastings and Geoffrey Johnson Smith.

Milne, in his 1988 memoir, outlined the programme's formula: one serious interview with a politician, one lighter one with a star of show business, ending with something that would "probably verge more towards the eccentric". This was how he described a typical edition: "Cliff trying to get past the guard of the late Krishna Menon, then Indian Minister of Defence...; a conversation with Brigitte Bardot at the height of her power to dazzle and mesmerise; an interview with a man in Bristol who had by dint of great effort brought forth a bent egg."

Viewers liked Highlight's irreverent approach and in 1957 the chance came to deploy it on a larger canvas. Until then there had been no television scheduled between 6 and 7 in the evenings, to allow parents to get young children to bed: the so-called Toddlers' Truce. At the instigation of the commercial channel the arrangement was abandoned, so material had to be found to fill the extra hour.

Milne and Baverstock were asked to devise a current affairs programme with the widest possible appeal that would last 45 minutes every weeknight. They decided that Highlight was the ideal template for the new show – to be called Tonight – and they invited Michelmore to be its host.

In his 1986 autobiography Two-Way Story, written jointly with Jean, Michelmore set out Tonight's ethos: "The concept of the programme was that it should be on the side of the audience. It would look at people and events as ordinary people looked at them, and take the attitude and ask the questions that ordinary people would ask. At no time were we to ... give the impression that we were superior. All these years later it seems strange that we had to be so conscious of the patronising attitude which had been so prevalent in many BBC programmes."

Tonight got off to a shaky start – one critic described how Michelmore "sits about on a desk making bad jokes and smiling hopefully at his viewers" – but it soon hit its stride and became required viewing for millions. And the reviews became more affectionate, reflecting how he was being accepted as a benign, avuncular, presence in the nation's living rooms: "a comfortable owl of a man"; "John Bull of the small screen"; "the face that dogs, children and maiden aunts trust on sight". He garnered several industry awards, including TV Personality of the Year in 1958.

The programme ran for 1,800 editions and made the reputations of such stalwarts as Alan Whicker, Derek Hart, Slim Hewitt, Fyfe Robertson and Cy Grant, with his topical calypsos. In 1965 it was taken off air and Michelmore became joint master of ceremonies of 24 Hours, a new programme screened in the late evening, with a more political agenda than Tonight.

He gave it up in 1968 partly because of the anti-social working hours and partly because, as he wrote: "There comes a time, even in television, when you begin to feel that it has gone on rather too long for your own comfort. There are those who play the games of power and stay the course far longer, almost for ever... I left that to others."

He decided to go into business on his own account, setting up a company to make video cassettes in collaboration with the record company EMI. But he did not abandon television or radio and was still seen and heard in a number of other roles, including hosting the BBC's general election coverage, regular specials on the American space programme and presenting Wheelbase, an early motoring magazine, much more staid than Top Gear. He also interviewed celebrities in With Michelmore, where among his guests were Field-Marshal Montgomery, Matt Busby, Ginger Rogers and David Niven.

In 1969, the year he was awarded the CBE, he began a new career as a travel broadcaster, presenting the Holiday programme for the next 17 years. As a by-product of this globe-trotting lifestyle he wrote numerous travel articles, many of them for the inflight magazine High Life. By 2000, when Jean died at the age of 76, he had given up nearly all his broadcasting, journalism and business activities.

Towards the end of Two-Way Story, he speculated on what his obituarists might record: "Michelmore found criticism hard to accept and could be intolerant even when proved wrong... His temper was combustible... Popularity was not important to him... Direct rather than subtle, he never claimed to be a patient man." Less self-critically, he added: "They might also say that I had been extremely fortunate to have achieved a measure of success in broadcasting in spite of lacking the intellectual powers and education of some of my contemporaries and the physical attributes of others."

Clifford Arthur Michelmore, broadcaster: born Cowes, Isle of Wight 11 December 1919; CBE 1969; married 1950 Jean Metcalfe (died 2000; one daughter, one son); died 17 March 2016.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments