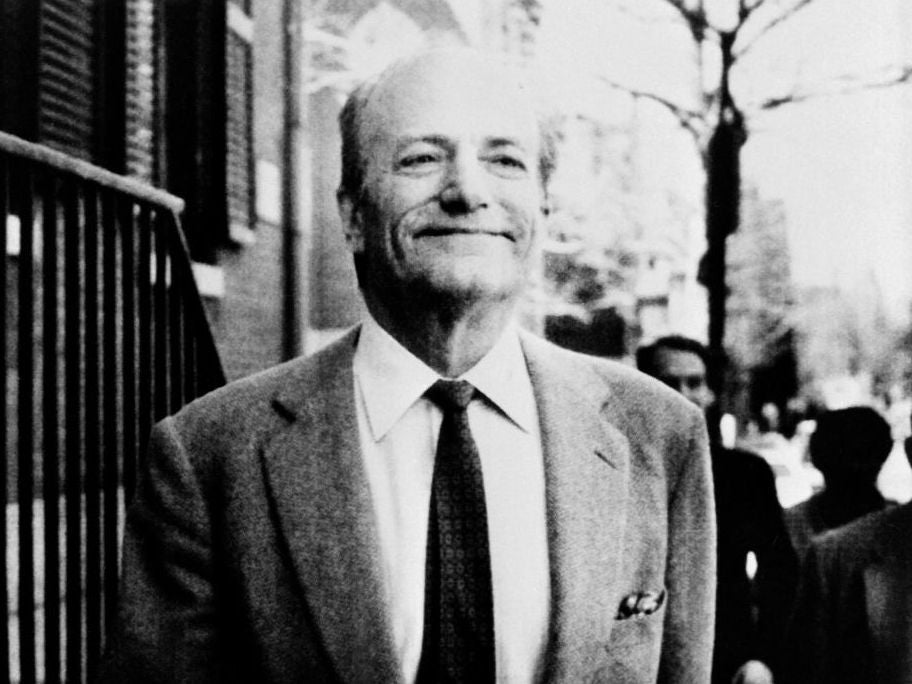

Claus von Bulow: Socialite acquitted of killing his wife after a trial that gripped America

The raffish Dane whose extraordinary story was told in the Oscar-winning film ‘Reversal of Fortune’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On 10 June 1985 in a US courtroom, Claus von Bulow was found not guilty of trying to murder his millionaire wife, Sunny, after a sensational trial televised live to an enthralled American public – with the rest of the world rapt.

Von Bulow, who died aged 92, had been found guilty at a previous trial and received a 30-year sentence but the verdict was quashed because the prosecution, it turned out, had withheld crucial evidence from the defence.

The case was, at best, circumstantial: because he had a mistress, TV actress Alexandra Isles, a divorce would mean being disinherited; Sunny’s medical tests included an (unconfirmed) high-insulin reading; a hypodermic needle was found in Von Bulow’s sponge bag; and a servant reported seeing an insulin vial some months earlier in the same sponge bag.

While Von Bulow was wealthy in his own right he stood to gain $14m (£11.1m) from Sunny’s will – she was fabulously rich. The marriage became celibate but remained amicable. Sunny’s medical records show that she drank and took large amounts of prescription medicines, including tranquillisers and barbiturates.

In December 1979 she went into a brief coma from inhaling vomit after taking alcohol, barbiturates and tranquillisers. Nearly a year later she took 70-100 aspirins after Von Bulow’s mistress, who wanted marriage, sent her evidence of their affair. Three weeks later, dopey with drink and drugs, she slipped and fell on her bathroom floor, and was found unconscious some time later. She went into a persistent vegetative state in 1980, where she remained until her death 28 years later.

Hospital tests for insulin were unreliable at that time. False positives were common, and it was considered essential to confirm any abnormal result. Sunny’s blood showed an unconfirmed high insulin level. This was later shown to be an artefact (that is, a result of the preparative or investigative procedure).

At the first trial, Sunny’s German maid, Maria Schrallhammer, testified to having seen insulin in Von Bulow’s sponge bag eight months before her mistress’s final coma. She was clearly believed. Later, it was shown that she had not originally mentioned this to the stepchildren’s lawyer, who had taken notes – which the defence did not see until the second trial.

At that second trial she could not explain why she had said nothing at the time, and nothing to the lawyer; she was clearly not believed.

The charge that Von Bulow had injected insulin to kill Sunny did not hold when it was shown the act of removing a needle from the skin wipes it clean of insulin.

Also, nine medical experts specialising in insulin and hypoglycaemia showed at the second trial that Sunny’s coma could not have been due to insulin. One of these witnesses was Professor Vincent Marks of the University of Surrey.

As there was no crime, there could be no criminal, and the Dane was acquitted. Von Bulow’s appeals lawyer, Alan Dershowitz, wrote a book about the case, but it was emasculated after legal threats from Von Bulow’s stepchildren and omits the complex medical details which were Von Bulow’s strongest evidence (a film based on Dershowitz’s book was released in 1990 – Reversal of Fortune, starring Glenn Close and Jeremy Irons, who won an Oscar for his depiction of Von Bulow).

Von Bulow was born Claus Cecil Borberg in Copenhagen. His father, Svend Borberg, was a successful a playwright and theatre critic and his mother, Jonna, nee Von Bulow, was the daughter of a prominent politician and banker.

After his parents divorced, Claus was brought up by his mother, who changed his surname to Von Bulow.

Von Bulow was considered to have weak lungs and was sent to a Swiss boarding school in St Moritz for five years. After the summer of 1938, when war was imminent, his parents felt the journey through Germany to Switzerland was unsafe, and sent him to a Danish boarding school, Herlufsholm.

Jonna von Bulow had moved to London in 1939, and by Christmas 1942 wanted Von Bulow to join her from Nazi-occupied Denmark. Two of her admirers were the Swedish ambassador and a cabinet minister. She finagled this with skill. Firstly, Von Bulow’s father obtained permission from the German ambassador in Copenhagen for Von Bulow to go to Sweden for Christmas. Then Von Bulow’s mother’s admirers between them arranged permission for Von Bulow to enter Britain, smuggled on a diplomatic flight.

Aged 15, Von Bulow was considered too old to fit in at an English school so he crammed with Gabbitas-Thring – the scholastic agency now called Gabbitas – while his mother paid a visit to GM Trevelyan, master of Trinity College Cambridge. Von Bulow started there in 1943, aged 16, studying law.

He graduated shortly before his 19th birthday and, being too young to be admitted to barristers’ chambers, spent a year studying political science at the Sorbonne. He then became a barrister in Quintin Hogg, later Lord Hailsham’s chambers. He stayed there for 10 years, until 1960, and moved to become chief executive for Getty Oil.

In 1963 he met Princess Martha von Auersperg, the pretty, intelligent but only child of a deceased American billionaire. She was universally known as Sunny. She was unhappily married to a penniless philandering German prince, Alfred von Auersperg. Von Bulow and Sunny fell in love and secretly courted while she got a divorce.

They married in 1966 and moved to Fifth Avenue, New York, with a magnificent summer home in Rhode Island. Sunny’s son and daughter by her first marriage, lived with them. Her mother, and her maid Maria Schrallhammer, may have resented the marriage because Sunny could no longer use the title of “princess”.

Throughout the trials and afterwards, Sunny’s two older children hired a public relations consultant to brief the press with the case against their stepfather.

Her mother had decided on disinheriting Von Bulow’s daughter, who survives him, in favour of the two Auersperg siblings. After three years of civil litigation, Cosima von Bulow was reinstated as a beneficiary after Von Bulow agreed never to “tell his story” and dropped his claim against Sunny’s estate.

Von Bulow later moved to London, where he reviewed books, plays and opera for publications such as The Spectator and the Catholic Herald. His many friends found him honourable, cultivated, charming and slightly raffish.

Claus von Bulow, socialite, born 11 August 1926, died 25 May 2019

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments