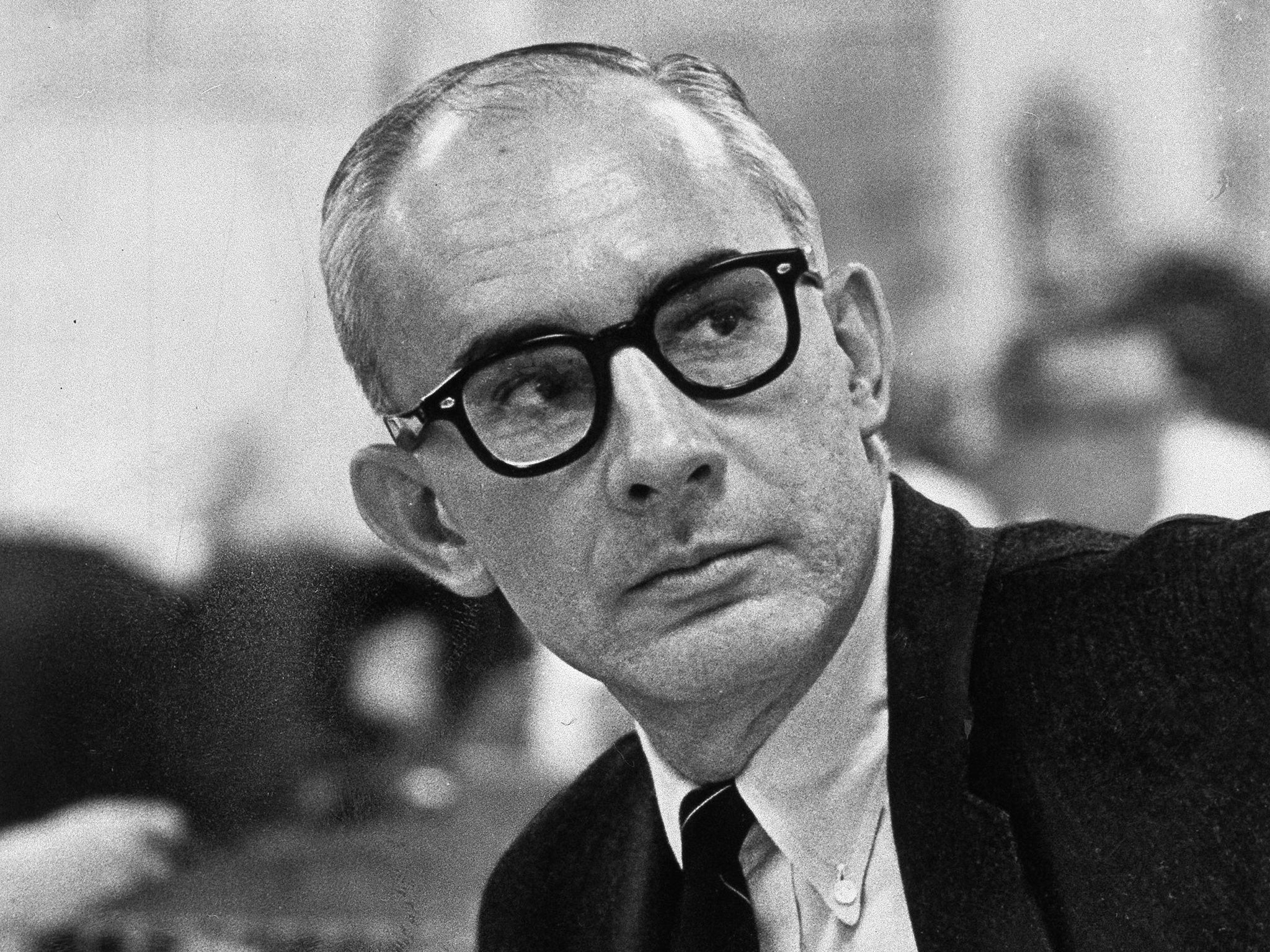

Claude Sitton: Reporter whose unflinching despatches from the US's southern states put civil rights on the front pages

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Claude Sitton’s powerful reporting for The New York Times on church bombings and other episodes of violence across the southern states of the US set a standard for other journalists and drew national attention to the civil rights struggle. In 1983 he won a Pulitzer Prize for commentary as editor of the News & Observer in Raleigh, North Carolina, but his earlier experience as the Times’s southern correspondent helped transform the nation’s debate on civil rights.

From 1958 to 1964 Sitton wrote about nearly every aspect of the movement, including voting rights, school desegregation and the unsolved killings of civil rights workers. Many of his reports were on the Times’s front page, bringing a fresh urgency to the issue. Some of his most evocative articles captured the sense of terror sowed by local police and white supremacist groups across the South. “A group of 13 law officers and roughly dressed whites clumped through the door” during a voter registration meeting at a black church in Georgia, Sitton wrote in 1962. “One pointed his arm at three newspaper reporters sitting at the front and said: ‘There they are.’ At the same time, a civil rights worker standing at the pulpit read a verse from the Bible: “We are counted as sheep for the slaughter.”

In 1961 Sitton rode the first bus in a convoy of Freedom Riders from Alabama to Mississippi, and was present in 1963 when the Alabama Governor George Wallace took his “stand in the schoolhouse door” in an effort to prevent African-American students from enrolling at the University of Alabama. The same year, Sitton wrote about deadly riots that accompanied the desegregation of the University of Mississippi; the killing of NAACP official Medgar Evers in Jackson, Mississippi; and the morning bombing of a black church in Birmingham, Alabama, that left four girls dead. He noted the subject of the girls’ Sunday school lesson that day: “The Love That Forgives.”

Sitton used public payphones to file his stories, believing his hotel telephones might be bugged. He would not sit in a restaurant with his back to the door. On a single day, he later recalled, he had five cars rented and an airplane on standby to take him quickly out of a Mississippi hot spot.

After serving as the paper’s national editor from 1964 to 1968, Sitton moved to Raleigh, where he edited the News & Observer for 22 years.

Claude Fox Sitton, journalist: born Atlanta, Georgia 4 December 1925; married Eva Whetstone (two daughters, two sons); died 10 March 2015.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments