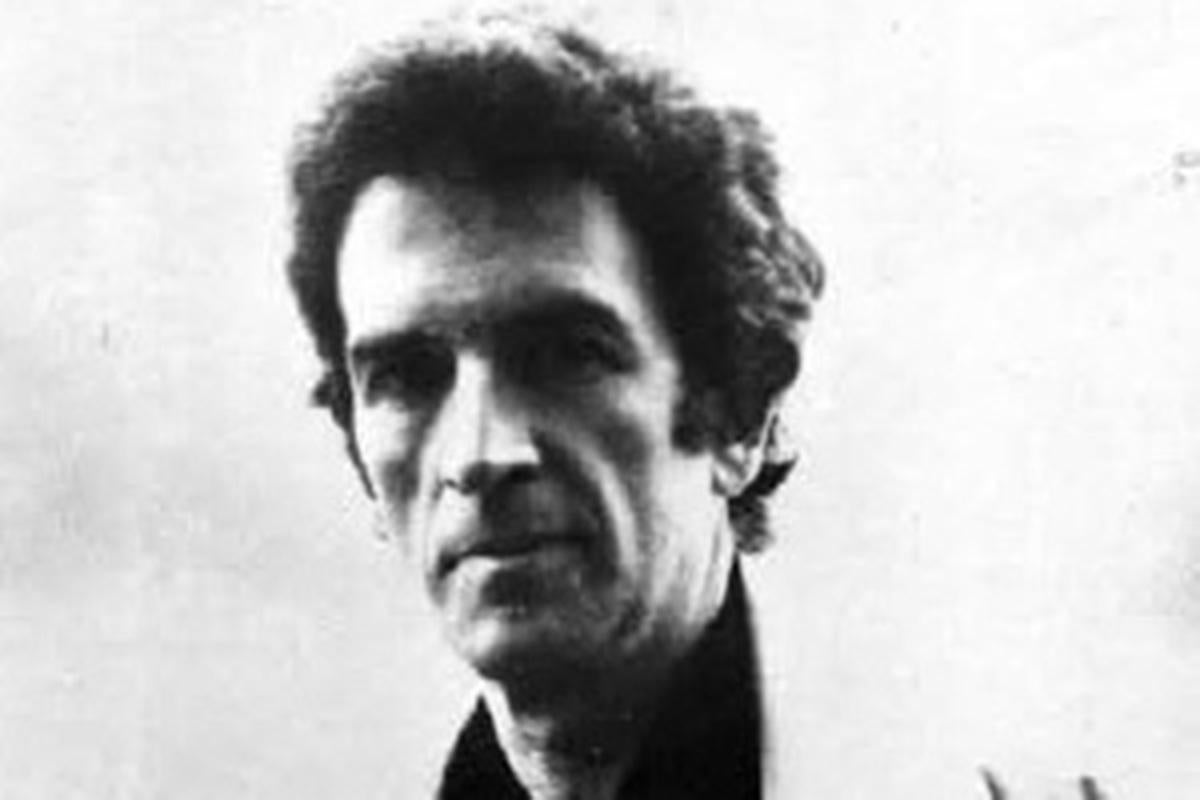

Clancy Sigal, radical, agent and writer

Blacklisted in Hollywood, he became the darling of London’s literary left

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.He was a street-corner communist agitator in the early 1940s, then a Second World War soldier who stared down one of the chief architects of the Holocaust at a Nazi war-crimes trial. In Hollywood, he was Humphrey Bogart’s agent before being blacklisted during the McCarthy era. He was a promising novelist in the 1960s, experimented with LSD in London and was the model for a character in one of the 20th century’s most celebrated novels.

In his 90 adventurous years, until his death on 16 July in Los Angeles, Clancy Sigal led a life overflowing with action, famous names, firings, breakups and a vision of America – at once earnest and cynical – born of many years as an expatriate.

Among his several novels, one (Going Away) was a finalist for America’s National Book Award. Since its first US publication in 1962, it has become a cult favourite and has been compared favourably to Jack Kerouac’s On the Road as a restless portrait of 1950s America.

“It was as if On the Road had been written by somebody with brains,” critic John Leonard wrote in The New York Times about Sigal. “His intelligence is always ticking. His ear is superb. His sympathies are promiscuous. His sin is enthusiasm.”

There were countless love affairs along the way, and Sigal was briefly part of the Paris intellectual world of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, the author of the feminist manifesto The Second Sex. Sigal hoped to seduce De Beauvoir, but he failed in that amorous attempt and was hastily driven out of Paris, by some accounts, at the point of a gun.

He moved in 1957 to London, where he rented a room from writer Doris Lessing, who 50 years later won the Nobel Prize for literature. During their four-year affair, each of them furtively read the other’s diaries and notebooks. Sigal was clearly the basis for the character of Saul Green, a handsome “American lefty” who was the lover of Anna Wulf, the protagonist of Lessing’s 1962 novel The Golden Notebook.

Sigal spent 30 years in Britain, working as a journalist and BBC commentator before returning to the US in the late 1980s. Rejuvenated in a city he once condemned as a place of “too many freeways, too much sun, too much abnormality taken normally”, he wrote screenplays and published several books, including a memoir about the woman who occupied his thoughts more than any other: his remarkable, cinematically colourful free spirit of a mother.

His story began in Chicago, where he was born on 6 September 1926, as Clarence Sigal (named after a friend of his mother’s, the lawyer Clarence Darrow, who was known for taking on challenging cases, including the Scopes Monkey Trial the previous year). In his youth, a co-worker mispronounced Sigal’s first name as Clancy, which he soon adopted. His name led many people to believe that he was half-Irish and half-Jewish. In fact, both parents were Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, although they never married.

His mother, Jennie Persily, roamed the country as a union organiser. His father, Leo Sigal, was also a union organiser but was married to another woman, with whom he had a separate family. The younger Sigal saw little of his father after the age of 13. Mother and son travelled around the country together, as she tried to rally workers. He was five the first time he spent a night in jail with his mother.

In a 2006 memoir about her, A Woman of Uncertain Character, he recalled sitting in a Southern police station while his mother was being interrogated: “Ma recrosses her silk-stockinged legs, reaches into her purse, pulls out a Pall Mall, and takes her time lighting it. Blows a perfect smoke ring.” The next morning, they were told to leave town.

Sigal was 15 when he joined the Communist Party – a move his mother opposed. He served in the army during and immediately after the Second World War. In 1946, he went to the Nuremberg war-crimes trial with the aim of assassinating Hermann Göring. After his gun was seized at the courtroom door, Sigal could only engage in a stare-down with Göring.

After the war, Sigal studied English at the University of California at Los Angeles, where he was an editor of the campus newspaper. He occasionally engaged in heated political debates with two other UCLA students, HR Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, who became top White House aides to Richard Nixon and were imprisoned for their roles in the Watergate scandal.

Sigal graduated in 1950, then went to work at the studio of Columbia Pictures, where he was fired by Columbia boss Harry Cohn for using studio equipment to make copies of radical leaflets, which he dropped over Los Angeles from an aeroplane. He then joined the talent agency of Sam Jaffe, where his clients included Bogart, Barbara Stanwyck and Donald O’Connor.

Two prospective clients he turned down were a “hillbilly singer” named Elvis Presley and a young “mumbling” actor, James Dean. As Sigal’s political sympathies became known, he left Hollywood and travelled around the country by car – and this became the subject of Going Away, which, “better than any other document I know,” Leonard wrote in the Times, “identified, embodied and recreated the post-war American radical experience.”

While living in Britain, he published Weekend in Dinlock, a slightly fictionalised account of the culture of a Yorkshire coal-mining community, often likened to George Orwell’s The Road to Wigan Pier. In the early 1960s, he developed a friendship with the charismatic psychologist and LSD exponent RD Laing, whom he came to see as a manipulative cult leader. He drew a scathing portrait of Laing in a 1976 novel Zone of the Interior.

On return visits to the United States, Sigal took part in civil rights organising in the South and the 1963 March on Washington; in the late 1980s, he settled in Los Angeles, where he taught journalism at UCLA and other colleges.

In 1992, he published a novel about an expatriate American radical in Britain, The Secret Defector. With his second wife, Janice Tidwell, he was a screenwriter of In Love and War, a 1996 film starring Sandra Bullock and Chris O’Donnell about Ernest Hemingway’s experiences in the First World War. He also helped write the screenplay of Frida, a 2002 biopic about Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, starring Salma Hayek, Alfred Molina and Antonio Banderas.

Sigal’s first marriage, to Margaret Walters, ended in divorce. Survivors include Tidwell, his wife of 24 years, and their son, Joseph.

In addition to the memoir of his mother, Sigal published a book about Hemingway and, last year, a memoir about his years in Hollywood, Black Sunset. He continued to publish essays until several weeks ago. Tidwell said Sigal “talked incessantly about his mother,” whom he described in his memoir as “a warrior queen, a crazy bohemian.”

Like her son, she carried on multiple love affairs and was volatile, passionate and proudly radical. “It seemed as if all that anger, resentment, and pent-up fury she could never articulate, for fear of being consumed by it,” Sigal wrote, “shot straight into my veins.”

Clancy Sigal, writer and activist, born 6 September 1926, died 16 July 2017

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments