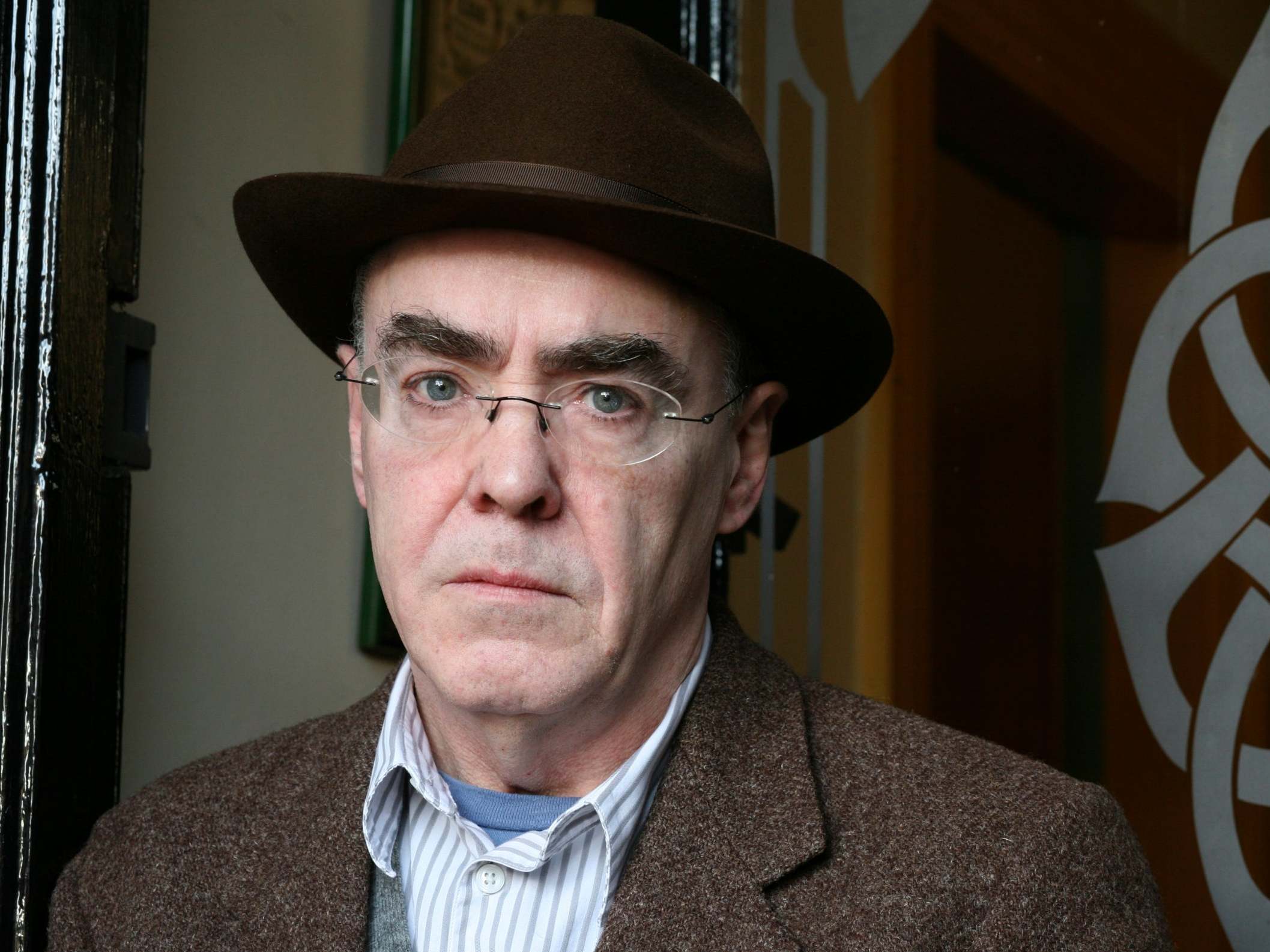

Ciaran Carson: Northern Ireland poet who brought a musical sensibility to his verse

He wrote with skill and care about the Troubles but rejected the epithet ‘social poet’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ciaran Carson, who has died aged 70, was a prolific poet, writer and musician who published 16 collections of poetry and 10 books of prose and translations during his lifetime.

Carson was born in Belfast in 1948 and grew up in the Falls Road area. His love of words came from his parents Mary and William, a postman and language enthusiast, who spoke only Irish with the family. One of four children, he and his siblings learnt English from friends in the street and at school. He later recalled: “The Irish I had was the language of home, it wasn’t the kind of language that handled all that stuff about the outside world and the abstract ideas and ideologies.”

He was educated at St Mary’s Christian Brothers’ Grammar School and Queen’s University, Belfast (QUB), graduating in English in 1971. While at university he joined some of the later meetings of the Belfast Group, created by the poet Philip Hobsbaum in 1963. Over its nine-year history the group met weekly, with members of the workshop including the poet Paul Muldoon, novelist Bernard MacLaverty and Seamus Heaney, who believed that it “ratified the idea of writing”.

Carson recalled of the meetings: “We would talk books, sport, politics, music, art and the weather. I think we were mutually supportive, but heavy slagging was also par for the course.”

Carson published his first volume of poetry, The New Estate, in 1976. Like much of his work around this time, the anthology was inspired and informed by ideas of place and contemporary events. For example, in his fourth collection, Belfast Confetti (1989), the title poem recounts a bombing in the city, in a staccato rhythm of punctuation and gunfire:

Suddenly as the riot squad moved in it was raining exclamation marks,

Nuts, bolts, nails, car-keys. A fount of broken type. And the explosion.

Itself – an asterisk on the map. This hyphenated line, a burst of rapid fire...

I was trying to complete a sentence in my head, but it kept stuttering,

All the alleyways and side streets blocked with stops and colons.

It has since become one of his best known works. But despite the subject of the poem, he always eschewed the label “social poet”, stating: “I can’t as a writer take any kind of moral stance on the Troubles, beyond registering what happens.” First Language, his sixth book of verse, moves away from place, exploring rather the structure and complexities of language itself. That book was awarded the TS Eliot prize in 1993.

An accomplished flute and tin whistle player, Carson spoke in interview with the poet Terence Winch about the interplay between words and music in his writing process. “When I write a sentence or if I write a poem, I’m always conscious of having to have some sort of a structure in the sentence that has to confirm to a pattern of sound ... At times I write well in writing, the sound or the structure of the reel would be at the back of my mind as something to hold onto whilst the sentence unfolds itself.”

Carson was the traditional arts officer for the Arts Council of Northern Ireland from 1975 until 1998. It was during this time that he met fellow musician Deirdre Shannon, whom he married in 1982. Out of the office, she and Carson would undertake “field work”, bringing his music and words to the back rooms of bars and pubs across Ireland.

On leaving the Arts Council, he was appointed professor of English at QUB, becoming the director of the university’s Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry five years later.

A skilled translator of poetry, Carson tackled authors as varied as Baudelaire, Ovid, Mallarmé and Dante Alighieri. His remarkable English-Irish interpretation of Dante’s Inferno (2002) was described by one reviewer as “a creative transformation that deserves our highest admiration” and went on to win the Oxford Weidenfeld Translation Prize.

Once asked what his epitaph might be, Carson replied with the name of a jig he had played on his flute for much of his life, titled simply “Happy to Meet and Sorry to Part”.

He is survived by his wife Deirdre and their three children.

Ciaran Carson, poet, born 9 October 1948, died 6 October 2019

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments