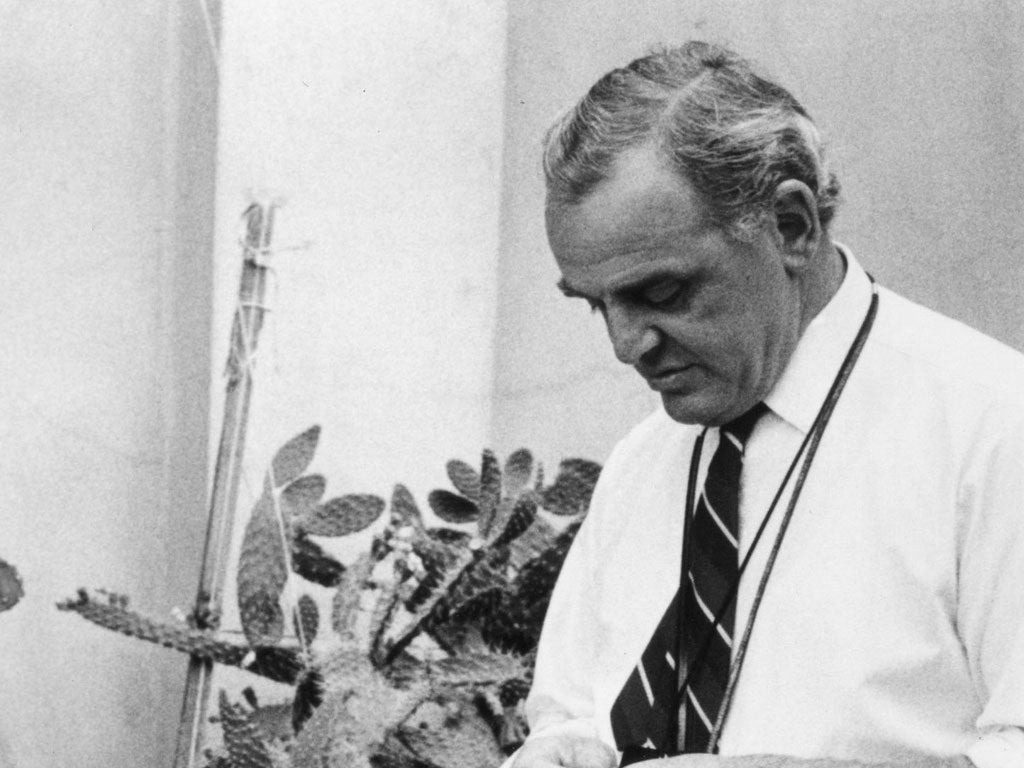

Christopher Challis: Cinematographer celebrated for his unforgettable images

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Christopher Challis was one of the leading cinematographers of British cinema's heyday, whose films framed tales of dance and derring-do, romance and comic invention. His lens introduced audiences to the cherished celluloid vehicles Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and Genevieve, and as the last of "The Archers", the creative team helmed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, his place in film history is as indelible as his images are unforgettable.

He made 11 films with Powell and Pressburger, initially as camera operator before progressing to cinematographer for The Small Back Room (1949). The following year, for their classic The Red Shoes, he went back to camera duties to work under the tutelage of the legendary director of photography, Jack Cardiff. From thereon Challis would be the pair's photographer of choice, creating striking visuals to their ethereal tales, including the vibrant colourful theatrics of The Tales of Hoffmann (1951) and the sweeping monochrome landscapes of Ill Met by Moonlight (1957).

Challis had a practical approach to the business of film-making from his first production, a school newsreel shot on a 16mm camera with film stock financed with school funds. Its success on Speech Day convinced Challis that cinematography was "a piece of cake". Gaumont British News gave him his first slice of the cake, taking him on as assistant cameraman in the mid-1930s. His first solo story came when he jumped out of a taxi and raced into Green Park to capture the comic scene of two London Zoo keepers attempting to net an escaped eagle. His footage lit up theatres the same afternoon.

He got a taste of creative work assisting on Alexander Korda's The Drum, an ambitious Technicolor epic shot on location in India. A series of travelogues followed which brought him to Cardiff's attention. However, war loomed and Challis joined the RAF Film Production Unit and refocused his talents to film operations abroad, assignments which took him to Casablanca, Lisbon and the Hague.

In 1946, on Cardiff's recommendation, he was interviewed by Michael Powell to be camera operator on the transcendental love story A Matter of Life and Death. Powell, a brusque character, stared him down in silence and then offered him the job. One of his compositions on the film's iconic heaven sequence invited the director's wrath. "If you don't like it you do the next one," Challis retorted. "Print it," said Powell, beginning a lifelong friendship. "He liked people to stand up to him," Challis judged later.

His other key partnership was with the director Stanley Donen, with whom he filmed six features, including the Gregory Peck thriller Arabesque, which won Challis a Bafta. He thrived in the face of adversity, as illustrated by the shoot for one of his favourite films, Genevieve. The charming romantic comedy about a London to Brighton vintage car race was made on a shoestring budget within a few miles of Pinewood Studios. Challis filmed until the light meter said otherwise to hit deadline. Hollywood glitz left him cold but he bonded with understated British stars such as Kenneth More, Edward Fox and Dirk Bogarde.

In all he shot over 70 films, ranging from Carl Foreman's anti-war statement The Victors (1963) to Billy Wilder's romping The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970) via the perennially popular Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968). He believed that directors don't always possess a visual approach. "The ones who do," he said, "come as a refreshing alternative."

Filming was often a family affair, with his wife Peggy and children in attendance. If Challis was unimpressed by celebrity, then it was clearly a shared trait. One morning, on location in Scontland for To Catch a Spy (1971), as Peggy ate breakfast in an Oban hotel a tartan-clad Kirk Douglas sat down at her table and asked who she was. "I'm Chris Challis's wife," she replied, "and who are you?"

Challis was a keen sailor and, smoking his trademark pipe, frequently shot at sea, most notably on HMS Defiant (1962) and The Deep (1977). Towards the end of his career he worked for a new producer, his son Drummond. The Riddle of the Sands (1979), an adaptation of Erskine Childers novel, was a boy's own adventure that found him in his element off the German Frisian Islands stringing up a camera in a yacht's rigging.

His final film was Steaming (1985), a conversation piece set in a bathhouse. It was the swansong for both its director Joseph Losey and its star Diana Dors, both of whom died before its release. Yet with all the talent on show, when the New York Times pinpointed the film's main attraction it was the camera's "seamless, fluid narrative" it praised. In retirement Challis wrote his affectionate and eloquent memoirs, Are they really so awful?

"I think the credit should go to other people rather than me," he said with characteristic modesty at a Bafta tribute last year. It was not an opinion shared by his peers. "It is not possible even to begin to take the full measure of the greatness of British film-making without thinking of Chris Challis," stated Martin Scorsese. "Challis brought a vibrancy to the celluloid palette that was entirely his own, and which helped make Britain a leader in that long, glorious period of classic world cinema."

Challis is survived by his daughter, the novelist Sarah Challis, and his son Drummond Challis, a film producer and farmer.

Christian House

Christopher Challis, cinematographer: born London 18 March 1919; married 1941 Sylvia (Peggy) Mauguerite (deceased; one daughter, one son); died Bristol 31 May 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments