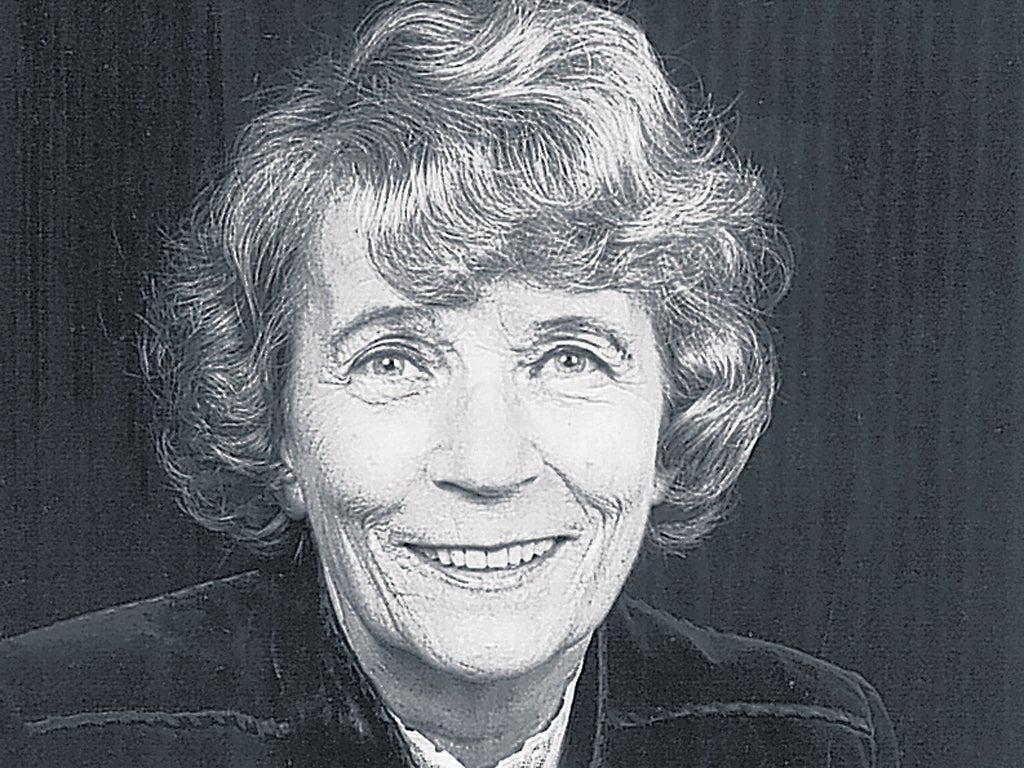

Christine Brooke-Rose: Writer acclaimed for her inventive and playful experimental fiction

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Christine Brooke-Rose was a richly innovative novelist and a formidable critic. She moved between languages, countries and identities without securing a fixed place in a literary canon or a national culture, but this mobility, combined with her inventiveness, humour and insight, madeher particularly well-equipped to grasp the contemporary world of signs and simulations.

Christine Frances Evelyn Brooke-Rose was born in Geneva in 1923, the younger of two daughters of an Englishman, Alfred Northbrook Rose (who had been both an Anglican Benedictine monk and an inmate of Parkhurst prison) and a Swiss-American, Evelyn Blanche Brooke (who later became a Benedictine nun). Brooke-Rose learnt English, French and German early but her childhood was marked by frequent moves, her father's desertion and death, and financial privation.

She went to school in London, Brussels and Folkestone and joined the Women's Auxiliary Air Force in the Second World War. She was posted to Bletchley Park, her "first university", which, by showing her the German perspective on the war, taught her "to imagine the other", a good training for a novelist. At Bletchley she met Rodney Bax, and they married in 1944.

Brooke-Rose read English at Somerville College, Oxford from 1946 to 1949. In 1948 she divorced Bax and married the Polish poet and novelist Jerzy Pietrkiewicz (later Peterkiewicz). After graduating, she went to London to live with Pietrkiewicz and to pursue a PhD in medieval literature at University College, which she completed in 1954. Unable to find an academic post, she became a freelance literary journalist, contributing to the New Statesman, Observer, Sunday Times and the Times Literary Supplement.

Her first book, Gold (1955), was a pastiche in the manner of the medieval religious poem Pearl, and she also published a critical study, The Grammar of Metaphor (1958). But she made her greatest mark with four novels: The Languages of Love (1957), The Sycamore Tree (1958), The Dear Deceit (1960) and The Middlemen (1961). Though she later repudiated these as lightweight, they are accomplished works; The Dear Deceit is especially interesting for its reverse chronology, which reconstructs the life of Alfred Northbrook Hayley from death to birth.

Brooke-Rose's fiction then took an abrupt turn. While recovering from a kidney operation, she wrote her first innovative novel, Out (1964), which used the present tense to evoke the consciousness of its elderly protagonist in a world of inverted prejudice where the "colourless", victims of a strange radiation sickness, are the objects of discrimination. Out won the Society of Authors Travelling Prize.

Her next novel, Such (1966), which shared the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, deployed astrophysical metaphors to portray a psychiatrist reawakening from death to life and seeing people as a radio telescope sees the stars. Between (1968) eschews the verb "to be" and makes its nameless female narrator a French-German interpreter moving constantly between languages and cultures. Brooke-Rose also won the 1969 Arts Council Translation Prize for her version of Alain Robbe-Grillet's Dans le labyrinthe, and published a short-story collection, Go When You See the Green Man Walking (1970).

Brooke-Rose's marriage to Pietrkiewicz collapsed in the later 1960s and she accepted Hélène Cixous's offer of a post at the new University of Vincennes (Paris VIII), plunging into literary theory at its headiest moment and producing her most inventive fiction, Thru (1975), a free-floating campus novel whose fragmentary discourses and typographical devices can variously be attributed to students in a creative writing class, their tutor, his ex-partner, and the Master in Diderot's Jacques le fataliste.

After Thru, Brooke-Rose went on teaching at Vincennes, produced critical books and essays, made guest appearances at universities in America, Israel, Montreal and Switzerland, and was briefly to married her cousin Claude Brooke, from 1981-82. But nine years passed before she published her next novel, Amalgamemnon (1984). Its protagonist, Mira Enketei, is a teacher of literature and history facing redundancy whose narrative creates a sense of uncertainty by only using tenses, such as the future and the conditional, which describe possible rather than actual states of affairs.

Xorandor (1986) consists of adialogue, spoken into a pocket computer, between two children who discover an intriguing form of extraterrestrial life, a computer-rock, in a Cornish village, while Verbivore (1990) envisages a world in which computers, facing system overload, start to consume words and produce chaos. Textermination (1991) portrays a host of literary characters, from Homer's Odysseus to Salman Rushdie's Gibreel Farishta, who assemble to pray for the readers they need to keep them alive.

Brooke-Rose had retired to Provence in 1988 and her next book, Remake (1996), was an unusual third-person autobiography which reminds the reader that it is remaking rather than revealing a life – and "a remake is never as good as the original". Next (1998) is a mystery story without a solution which depicts homelessness in London, eschewing the verb "to have" to signal the dispossession of its 26 characters, each of whom corresponds to one letter of the alphabet. Subscript (1999) is an epic of prehuman history, tracing the development of life from one-celled organisms to early tribal culture. Her last book, Life, End of (2006) largely avoids the pronoun "I", except in dialogue, and sharply evokes the plight of the alert mind in an increasingly infirm body, "living on the razor's edge". But that, in a sense, was where Brooke-Rose had lived all her life.

Christine Frances Evelyn Brooke-Rose, novelist and critic: born Geneva 16 January 1923; Professor of English Language and Literature, University of Paris 1975–88 (Lecturer, 1968–75); married 1944 Rodney Bax (marriage dissolved), secondly Jerzy Pietrkiewicz (divorced 1975), 1981 Claude Brooke (divorced 1982); died 21 March 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments