Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

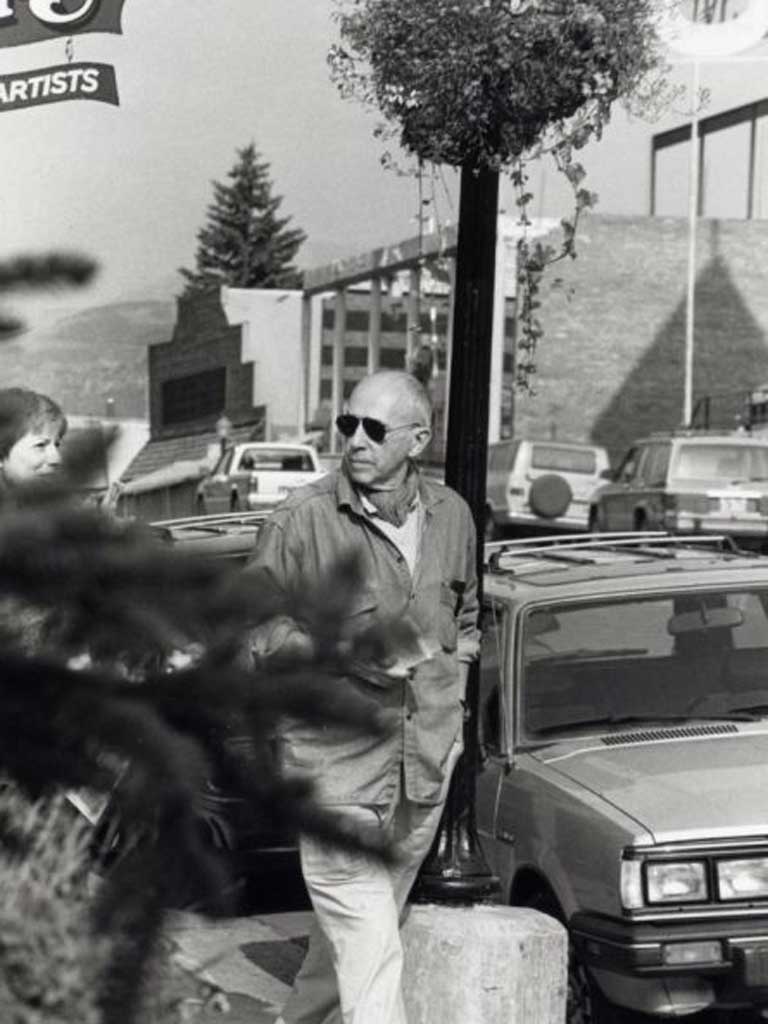

Your support makes all the difference.Chris Marker, who died on his 91st birthday in Paris was a man of many parts: film-maker, travel writer, piano player, novelist, actor, typographer and perhaps the first great artist of the digital age. Marker delighted in secrecy; he never abandoned the habits formed as a member of the clandestine French Resistance, and was assiduous in spreading false rumours about himself. He was born in 1921, Christian François Bouche Villeneuve, although there is some dispute as to where. Neuilly sur Seine – where he grew up – would seem obvious but Ulan Bator Outer Mongolia was Marker's own preferred birthplace.

At school he would gather in a local café where a young Jean Paul Sartre held forth on German phenomenology, and he then took a licence in philosophy at the Sorbonne, where his teachers included Gaston Bachelard. He joined the Resistance for, in his words, "the adventure rather than the ideology", and then the American Army when, for a brief period after the Battle of the Bulge, the Americans recruited Frenchmen directly into the American Army. He fought right through to the end of the war and one of his most treasured possessions was the signed letter from Eisenhower thanking him for his service.

A period playing piano in a bar came to an end when he joined the offices of Travail et Culture, part of the French adult education movement, in 1946. Originally his duties focused on the theatre but in the next room was André Bazin working on the cinema and the two became fast friends, working on a myriad of projects. This period of joyful creativity – " it was like '68 everyday," he was to say later – came to an end with the Cold War and the Communist Party's increasing control of their cultural front organisations.

If Bazin stimulated an already strong interest in cinema – on a clandestine mission to Geneva he had dropped into a cinema and seen a double bill of Citizen Kane and Hellzappoppin' – Marker's reason for choosing film as a vocation was that it seemed to be the best way to fulfil his primary passion – travel. He turned down Bazin's request that he edit Cahiers du Cinéma and started a travel book series at Seuil Le Petit Planète, many of which have become classics of travel writing.

His first film was a documentary of the Helsinki Olympic Games and he followed that with a joint project with Alain Resnais, Les Statues meurent aussi, a prescient study on the relations between colonialism and art. Sunday in Peking (1955) was the first of a series of films made of then inaccessible Communist regimes. Perhaps the most influential was Letter from Siberia, made in 1958. Bazin, in one of his last articles written before his tragically early death, hailed his friend's work as an "essay film". Marker has a strong claim to have created this ever more fertile genre.

Continuing to travel, camera in hand, Marker made films on Israel (Description of a struggle) and Cuba (Cuba Si) before filming his first masterpiece, Le Joli Mai, in 1962. This film, edited down to 150 minutes from the 55 hours shot, caught the people of Paris, on the cusp of the new audiovisual age, registering an eloquence and a world about to disappear. Like many of his films this was to be a considerable influence on others. Godard's trademark use of interviews seems borrowed from this film and Marker's films are a constant point of reference as Godard developed through the next five decades.

Just before the release of Le joli mai he shot his single most influential film, a 20-minute short composed almost entirely of still photos. Entitled La Jetée (The Jetty), it is set in a post-nuclear future and involved time travel as the survivors try desperately to summon both past and future to their aid. The hero is obsessed with memories of an event in his childhood at one of Orly airport's jetties. At the end of his film he travels back in time to Orly to discover that the event that obsessed him was his own death as agents from the future shoot him down. This remarkable film is a reference point for many subsequent science fiction films and was remade as Twelve Monkeys by Terry Gilliam in 1995, starring Bruce Willis and Brad Pitt.

Marker was one of the first to feel the political pulse of the Sixties and he soon threw his activities into a co-operative, Société pour le lancement des oeuvres nouvelles (Slon). Its first production was the compilation film Far from Vietnam ( 1967) but over the next few years it was to lend its skills to many of the struggles, particularly factory occupations, then convulsing French society. On his return to individual film-making Marker then made the single best film on the politics of that period, Le fond de l'air est rouge 1977 (English title: The grin without a cat). It charts the rise of political hope in the Sixties and the defeats of those hopes in the Seventies.

A much more personal film was Sans Soleil (1983), which returned to the theme of memory and the inability to ever remember fully. Shot between Tokyo, where Marker was then living in a luxury hotel, and Guinea Bissau, where he was training young African film-makers in conditions of extreme poverty, the film meditates on travel and politics as a young woman reads out the letters of the photographer Sandor Krasna, one of Marker's numerous aliases.

Marker's last 30 years saw him add prolifically to his already numerous films but it also witnessed his engagement with the digital world. He was an early aficionado of computers, and digital technology offered for Marker a way out of the inevitable linearity of film. In 1998 he produced the CD ROM Immemory, arguably the first great work of digital art, in which he was able to continue his investigations of memory in a medium that, for the first time, allowed Marker to explore the structure of memory with rather than against grain of the technology he was using.

He died working at his bank of computers in his studio in the 20th arrondisement of Paris.

Christian François Bouche-Villeneuve (Chris Marker), film-maker: born 29 July 1921; died 29 July 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments